It might be Richmond’s biggest push to create affordable housing. But many residents don’t even know it exists.

The graffiti all around town is straight to the point: Rent 2 High.

It’s a message city leaders heard. Just over two years ago, even before City Council declared that Richmond was in the midst of a housing crisis, officials were trying to find ways to incentivize developers to build more affordable units.

“We have a lot of residential housing being built in the city. You can see it with cranes everywhere in the city. And most of it is market rate,” said Sharon Ebert, Richmond’s deputy chief administrative officer for economic and community development. “What we weren’t seeing at the time in 2023 was the same amount of production in affordable housing units.”

The result was the Affordable Housing Performance Grant Program, a strategy that refunds developers any increases in real estate taxes that result from their creation of affordable housing — as long as they keep units affordable and invest in their upkeep.

Since then, Richmond has signed off on 25 agreements that, if all come to fruition, will add 3,213 affordable units to the city’s housing stock. Virginia Beach was so impressed by the results that earlier this year it modeled its own Attainable Workforce Housing Performance Grant program on Richmond’s.

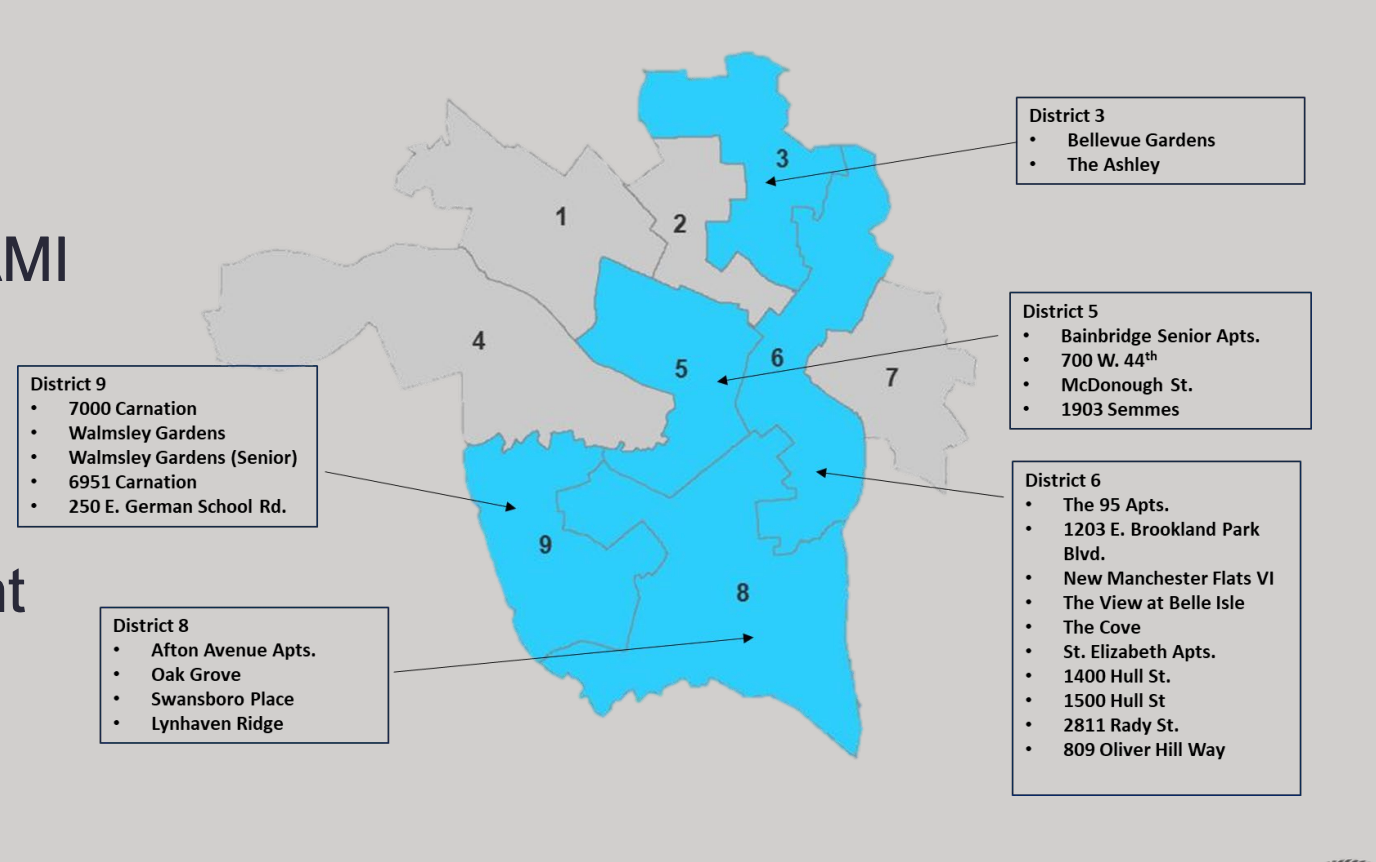

MAP: Click on a site for more details on its participation in the program.

Developers have described the program as a game changer when it comes to making the finances of a project work.

“If I'm looking at a site, and let's just say the border of Chesterfield and Richmond is here, and I have two pieces of land that are identical — both will be the same site work, same land cost — I can do the one in Richmond here and I can't do the one in Chesterfield,” said William Sexauer, a senior development manager with Lawson Companies, which is building two projects through Richmond’s program and trying to get approval for a third. “That is the difference it makes. It makes it possible when it otherwise would not have been possible.”

Still, skeptics have raised concerns about how affordable the new units actually are, as well as about how much future revenue the city is forgoing by rebating developers 15 to 30 years’ worth of increases in their real estate taxes. Anecdotally, some of the most frequent questions we get at The Richmonder are: What’s the deal with the city’s affordable housing performance grants? Are they actually working, or are they just a giveaway to developers?

Here’s how it all works.

Why did the city create this program?

The primary driver for Richmond’s creation of the program was officials’ conclusion that the city is facing a housing crisis.

While housing pressures are by no means unique to Richmond, the city has been hit hard by the dislocations of the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought thousands of people from higher-wage cities south and drove up local prices significantly.

Richmond began encouraging the rehabilitation of affordable housing units with a partial tax exemption in 2019, a reworking of an earlier, broader abatement program that was scrapped. But Ebert said the city “had nothing for new construction.”

“There was nothing in the state law that would allow us to grant tax abatements, tax exemptions or tax rebates to incentivize developers for new construction work,” she said.

That changed in 2022, when the Virginia General Assembly passed a law allowing economic development authorities to make grants for new affordable housing construction. It was that law that cleared the way for the city to develop the AHPG program through the Richmond Economic Development Authority.

What the data say about Richmond’s housing market

According to data from the Richmond Association of Realtors, the median sales price for a single family home in the Richmond metro area more than doubled over the past decade, from just over $200,000 in 2014 to roughly $430,000 last year. The median price of condos and townhouses also skyrocketed over that period, from $200,000 to about $375,000.

At the same time, the number of lower-priced homes available on the market has tumbled. While roughly 11% of houses for sale in 2021 were priced between $100,000 and $199,999, only 1.5% were by the end of 2024.

Rental prices have also risen. A comprehensive housing market analysis conducted for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2022 found that between 2012 and 2022, average monthly rent in the combined Richmond-Chesterfield-Henrico market rose from just over $900 to almost $1,400. In March 2022, the report noted, “rents for professionally managed units in the city of Richmond averaged $1,752, $1,538, $1,763, and $2,095 for one-, two-, three-, and four-bedroom homes, respectively.”

Wage increases haven’t kept pace with those hikes. A 2022 report from the Richmond region Partnership for Housing Affordability found that “the typical renter household still has an income unable to afford the average asking rent, as well as the median home price in the city.”

Shortfalls in supply are part of the problem. One 2021 study by the General Assembly’s research arm found the city of Richmond had the state’s third-highest “unmet need” for affordable rentals, with an 11,600-unit shortage. Richmond’s housing crisis resolution put the figure even higher, at 23,320 units.

How do the grants encourage the development of affordable housing?

The grants work by offering developers a significant incentive to develop and maintain affordable housing units: long-term tax reductions.

Because the Virginia Constitution requires that taxes be uniformly imposed “upon the same class of subjects,” a local government can’t just decide to tax certain residential properties less than others. That means that whatever the local real estate tax is — in Richmond, currently $1.20 per $100 of assessed value — it must be applied equally to every property owner.

What the city can do is give back some of that money by setting up a program that asks the taxpayer to meet certain criteria. In the case of the AHPG program, Richmond is asking the developer to produce and maintain a specific number of affordable rental units.

Every year that a developer does, it receives a grant from the city for the “incremental real estate tax” — the amount its taxes have increased since it entered the agreement.

For example, say a developer buys an empty lot for affordable housing this year that has a tax liability of $1,000. The developer then builds out the housing complex, greatly increasing the value of the property and raising its tax liability to $10,000. When tax time comes around, it pays the city $10,000, and if it meets all the criteria in the agreement, the city gives it back $9,000.

Developers say the biggest difference the incentive makes is in filling financing gaps.

By lowering project expenses over time, the grant program “allows the property to take on more debt” and increases the ability of a developer to tap into other possible financing, said John Gregory of Lynx Ventures, which has had three projects involved in the program.

Sexauer echoed that view.

“It's not like they're just handing money to a developer to increase the amount of cash flow they're getting and increase the returns of their property,” he said. Instead, “it reduces the expenses of the property, which then allows us to go to our lender — who's normally Virginia Housing — and they'll provide more debt to us, which then makes the projects feasible that wouldn't have been feasible before.”

For the 1203 E. Brookland Park project being developed by Enterprise Community Development near Six Points in Richmond’s Northside, manager Kathleen Kramer said the lower operating costs let Enterprise borrow roughly $500,000 in permanent debt from Virginia Housing, which “allowed us to close any remaining funding gaps prior to construction closing.”

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.

What does ‘affordable’ mean?

Richmond’s definition of “affordable” is based on something called the area median income, or AMI, a measure of what people in the middle of a region’s income range earn.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development calculates the AMI using census data for regions all over the country every year and uses it to determine eligibility for housing programs. Many other state and local governments also rely on these numbers to design their own programs.

(One critical point: The AMI is calculated for the entire metropolitan area, not just the city. The federal government defines the Richmond metro area as a group of 16 localities ranging from Amelia County in the west to New Kent in the east and Hanover County in the north to Sussex County in the south.)

Nearly all — 21 of 25 — of Richmond’s grant projects require that occupant incomes and rents be restricted to an average of 60% AMI. The remaining four, three of which are being developed by Commonwealth Catholic Charities, require various mixes of units at anywhere between 0 and 80% of AMI.

For the Richmond metro area, the current 60% AMI that went into effect this May ranges from an income of $47,700 for a single individual to $54,480 for two people, $68,100 for a family of four and up to $89,940 for a family of eight.

Rental prices at 60% AMI would be limited to $1,192 for a studio, $1,277 for a one bedroom, $1,533 for a two bedroom, $1,770 for a three bedroom and $1,975 for a four bedroom.

The “average” provision written into the grant agreements is critical, said Ebert, because it lets developers include a mix of units as high as 80% AMI with those that are lower.

“We’re getting a greater range of incomes in each one of these projects,” she said. “From a social engineering perspective, that’s great, because you’re not concentrating households all together with one kind of income base.”

What is the status of the projects?

Of the 25 grant projects that have been approved, 15 are either underway or complete. Those that are finished and actively renting apartments include the 217-unit NOON Hioaks at 7000 Carnation St. and 65 units at The Cove at 512 Hull St.

See a full map of projects, with more information about each, here.

Uniquely, the Cove was approved for a performance grant after it had already been constructed. Members of Richmond’s Housing and Community Development Department said in an email that “there was originally no stipulation in the affordable housing performance grant application that a developer had to apply and be approved prior to the commencement of construction.

“This has since been explicitly stated and no other projects have been awarded an affordable housing performance grant following the completion of construction,” they continued.

Of the 25 that have been approved, 19 are found in the city’s Southside. Significant clusters can be found in Manchester, Swansboro and the Six Points area.

No projects have been approved in the West End-based 1st District; the 2nd District encompassing the Fan, Scott’s Addition and Carver; or the 4th District in the city’s southwestern corner.

According to the agreements, developers have 18 months from the time of approval to begin construction and three years to complete their project once construction begins. Performance grants don’t begin to be paid out until a project gets its certificate of occupancy from the city.

Exactly how many units each project includes can be trickier to determine. While City Council has to approve each agreement, several of the ordinances posted online omit the number of units the developer is committed to producing. Those documents also conflict in more than half a dozen instances with the tally of projects included in this year’s city budget.

For this story, The Richmonder confirmed conflicting numbers with city economic development officials to arrive at a total of 3,213 units that have been approved. Asked whether any of the agreements with missing or erroneous figures would need to be amended by Council, city spokesman Michael Hinkle said in an email that “only substantive amendments, as determined by the city attorney, have to be approved by Council.”

How long do the grants last?

The grants are for 30-year periods. After 15 years, the developer is required to prove to the city that it has made a certain amount of capital investments in the project to ensure it is being adequately maintained and updated.

All of the agreements calculate what that minimum investment should be by multiplying the number of units by $10,000. The View at Belle Isle project being developed by the Lawson Companies off Hull and Decatur streets, for example, has 116 units and must see $1.16 million in capital investments after 15 years of operation in order to continue getting the grants.

How does the city make sure the developers are meeting their obligations over time?

City officials say the program’s design helps ensure compliance: Every year the city will review whether projects have met the requirements before they agree to give them back the incremental real estate tax revenue.

Some of the compliance work will be done at the state level. Of the 25 performance grant projects that have been approved, 24 are using low-income housing tax credits, a federal incentive through the Internal Revenue Service that in Virginia is administered by the state housing agency, Virginia Housing.

“They’re the ones that are validating compliance, and that affordable housing developer would then have to be able to show them their files, their records, et cetera, and do audits of their documentation,” said Ebert. “We didn’t want to reinvent the wheel by having to do that ourselves. So long as it’s in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program, we will accept Virginia Housing’s authorization or certification that it met compliance with the IRS requirements.”

One advantage of that approach, said Sexauer, is that affordable housing developers are already familiar with the compliance process.

“Every year we have massive submissions to the IRS that certify that we’ve kept the rents up to the standard,” he said. And, he said, “you can’t get around the IRS. They are the head honchos when it comes to noncompliance.”

For the one project that didn’t use the tax credits — The Cove at 512 Hull St. — Richmond Housing and Community Development Director Merrick Malone said the city is using a compliance form that “mirrors” what Virginia Housing uses.

“All of our programs require compliance,” he said. “So we’ve got to make sure that that paperwork is there and that they're doing what they're supposed to be doing.”

Additionally, he said, Richmond will need to ensure that developers are making the capital improvement investments that are required after Year 15. Under the terms of the agreements, payouts after that time are contingent on those improvements being done. The city will also have to make sure that developers have made an effort to pay 30% of all construction costs to “minority business enterprises” and “emerging small businesses,” as defined in city code.

How much future revenue is Richmond giving up through the program?

While the affordable housing performance grant program doesn’t tap into any existing city funds, it does keep the city from collecting about $7.2 million in annual real estate taxes in coming years.

That has given rise to some questions about exactly how much future revenue Richmond can afford to forego, particularly as federal dollars dry up under the Trump administration and the city faces tighter budgets.

Officials acknowledge the financial impacts but say it isn’t quite so straightforward. Many of the parcels of land being developed through the program have sat vacant for a long time, they point out, meaning the city might not have seen increased tax revenue on them for years to come.

“If it was developed, worst case scenario, it would probably be for market rate housing, and it wouldn't address the need that Council put before us, which is, we're in a crisis,” said Ebert. “We have so many people moving into the city, and it's just compounding the already high assessments and pushing people, quite frankly, with lower incomes, out of the city to the counties to live.”

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.