How Richmond’s tax sale fund swelled to $9M, with no clear use for the money

When Richmond officials realized they had to find nearly $6 million to make an unexpected restitution payment to a wrongfully convicted man, some were worried the city just didn’t have that kind of money.

In this year’s budget talks, the prevailing view was that the city was painfully light on funds to spend on any new initiatives or priorities.

As it turns out, the city had more than $9 million stashed in a special fund that holds money from the city-overseen sales of properties long delinquent on real estate tax bills.

The revelation of the sum — which wasn’t clearly disclosed in the budget officials adopted in the spring — has raised questions about why a supposedly cash-strapped city had that amount of money available and apparently uncommitted to any particular purpose.

In 2019, the Council approved a policy to use the delinquent tax sale fund as a dedicated source of money for the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund. The thinking at the time was that when the city auctions off decaying, tax-delinquent properties in distressed neighborhoods, some of the proceeds should go toward the creation of better housing for city residents.

But it appears officials never made any transfers out of the tax sale fund for affordable housing purposes, even as the amount of money in the tax sale fund nearly tripled.

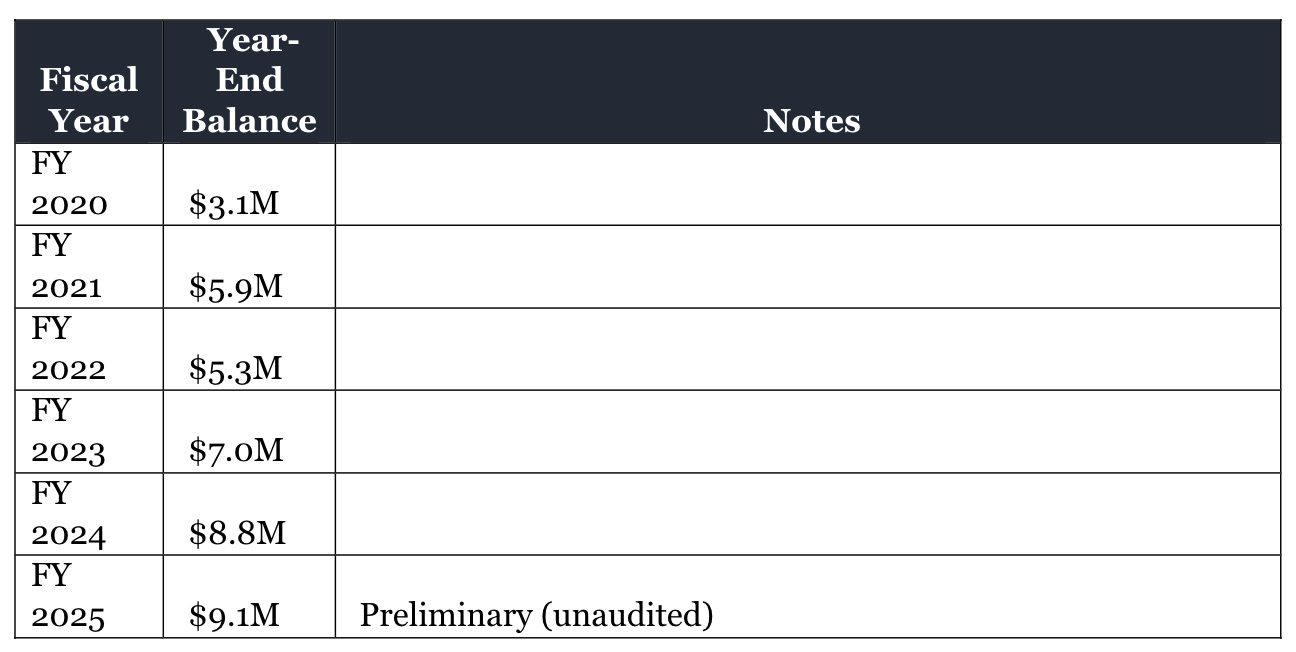

In fiscal year 2020, the end-of-year balance in the fund was $3.1 million, according to a city memo. By fiscal year 2025, which concluded this summer, the balance had grown to around $9.1 million.

Having that money available arguably worked to the city’s benefit. It will allow officials to make an unplanned but legally required $5.8 million payment to Marvin Grimm, who was wrongfully imprisoned for more than four decades after being erroneously convicted for the 1975 death of a local boy.

Gov. Glenn Youngkin had threatened to withhold state funding from Richmond unless the city agreed to pay Grimm quickly. By pulling that money from the tax sale fund, the city can pay Grimm without budget cuts or dipping into regular reserve funds meant for emergencies.

However, the proposed solution for the Grimm payment has drawn scrutiny to why so much unused money was in the tax sale fund to begin with.

The ordinance the Council approved in early 2019 called for up to $1 million to be transferred each year from the tax sale fund to the affordable housing fund, as long as there was money to do it.

Why that didn’t happen isn’t fully clear.

“We can’t speak to why funds weren’t appropriated from the special fund to the Affordable Housing Trust Fund in the past,” said city press secretary Mira Signer. “Transfers are subject to appropriations, so a legislative action is required.”

The city code says the finance director “shall” credit the $1 million to a special reserve supporting the Affordable Housing Trust Fund on an annual basis starting July 1 of 2019. If the policy had been followed, it could have added up to as much as $7 million for the Affordable Housing Trust Fund by this year.

The code says the money transfers are “subject to appropriation,” a standard clause that means the city isn’t obligated to follow through on policies unless they’re funded in the budget.

The Council can always follow up to ensure its approved policies are followed. But it’s the administration that writes the vast majority of the budget presented to the Council for approval. And the Council relies on the administration for updates on what money is available to spend.

The sponsor of the 2019 ordinance — Councilor Ellen Robertson (6th District) — wasn’t happy to learn it’s never been followed, apparently only because the city didn’t take the technical steps to move money from one account to another.

In an email sent Friday to her colleagues and other top city officials, Robertson said it was “extremely troubling” for the administration to suggest a different use for the money years after the Council was clear on how it should be used. She accused the executive branch of keeping money “hidden in accounts” to sidestep Council policy and use it for other purposes.

“The tax delinquent sales revenue is a dedicated source not a surplus to be used at will by [the] administration,” Robertson wrote. “It’s essential that Council ordinances are carried out and not disregarded.”

Robertson faulted the “past administration” for not telling the Council how much tax sale revenue the city had and not introducing ordinances to transfer the money. The Avula administration’s proposal to now use the money to pay Grimm, Robertson wrote, is “a violation” of the ordinance the Council already passed.

“Silence by council and the citizens is not an option,” Robertson wrote. “The city is in a housing crisis. It is not acceptable to repurpose dedicated revenues without proper justification and authorization. Our citizens are forced out of the city. Homelessness is out of control. Trailer courts and public housing are in deplorable conditions. Rent rates are through the roof.”

According to the city, there has been only one transfer out of the tax sale fund since fiscal year 2020. In early 2022, officials took $1.3 million out of the fund to support ongoing efforts to build a slavery museum and historic site in Shockoe Bottom.

Signer said Mayor Danny Avula, who took office eight months ago, wasn’t aware of the code section that instructs the city to use money from tax sales of delinquent properties for affordable housing. New Chief Administrative Officer Odie Donald II brought it to the mayor’s attention as part of a “deep dive” into the budget, Signer said.

“We’ve now built an extraordinarily talented team and they’re putting a plan in place for an affordable housing strategy, including a full understanding of the code and its requirements,” Signer said. “The mayor has made housing a pillar of his administration. He feels strongly that meeting the housing needs of a growing city means that we must show up in a way that allows Richmonders at every level to afford good housing in safe neighborhoods with strong public amenities.”

The Council is set to take up the proposal to use the money to pay Grimm at a committee meeting Tuesday.

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.

City says it stopped tax auctions due to COVID-19, and hasn’t restarted them

The city attorney’s office once had a goal of auctioning or collecting payment on at least 240 tax-delinquent properties per year, a performance metric meant to cut down on unpaid taxes.

The city stopped doing auctions altogether due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not yet restarted the process, according to a memo from Donald.

“The suspension of collection activities during the pandemic, coupled with the delayed resumption, has significantly limited the city’s ability to recover outstanding balances,” Donald wrote in the memo. “To address this, the city is preparing a structured plan intended to strengthen delinquent tax collections.”

City leaders often complain that Richmond’s finances are constrained by the large amount of tax-exempt land owned by VCU and the state. The suspension of tax auctions means the city isn’t using all the tools it has to try to collect revenue from property that is taxable.

Officials have conflicting incentives to collect taxes that are owed and return blighted properties to productive use, without causing more evictions or coming down too hard on those who simply don’t have the money to pay.

An internal audit of the tax sale process completed in 2021 faulted the city for having an “unwritten policy” of not initiating tax sales against owner-occupied properties. The auditor’s office recommended eliminating the “disparity” and treating all tax-delinquent properties the same.

“The disparity between owner occupied and non-owner occupied properties could create a negative perception of city procedures, hence decrease trust,” the audit report said. “Additionally, the city suffers financial loss due to uncollectable real estate taxes.”

Between fiscal years 2014 and 2023, there were 981 delinquent properties sold at auction, according to data provided by the city.

In fiscal years 2024 and 2025, there were zero auctions.

Virginia law allows local governments to pursue tax sales for properties delinquent on taxes for at least two years, or one year for particularly troublesome properties that have been formally condemned or deemed a neighborhood nuisance.

The city attorney’s office has to go through several steps before finalizing a tax sale, such as sending letters to the owner, publishing notices in a local newspaper and placing a lien on the property.

Money generated from tax sales also funds the costs to the city attorney’s office for carrying out the process. The Council’s 2019 policy specified that up to $1 million of any leftover funds should be directed to affordable housing. Because those transfers weren’t made, money not dedicated to affordable housing stayed in a fund controlled by the city attorney’s office.

Though the city attorney’s office has conducted no tax auctions in the last two budget years, officials said there can still be staffing costs for the office because delinquent property sales are typically a multi-year process.

Council staffers have recommended that the legislative body seek more information about whether any money from the tax sale fund is still available to be used for affordable housing.

Contact Reporter Graham Moomaw at gmoomaw@richmonder.org

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.