$126 million segment of Fall Line Trail could rewire Southside's transportation

Extending across six lanes above the James River, the Manchester Bridge was built for cars, and the stretch of Commerce Road into which it flows is similarly engineered: multiple north-south lanes, overhead signage, large parcels of land scattered with parking lots fronting on the street.

Over the coming decade, that picture could change dramatically.

This August, city leaders broke ground on the first Richmond trailhead of the Fall Line Trail at Bryan Park. But while the completed trail will run 43 miles from Ashland to Petersburg, local leaders and planners say one of its most significant benefits could be its expansion of bike and pedestrian infrastructure in Richmond’s Southside, which has long lagged other parts of the city in options to get around without a car.

“Southside has been underinvested, period,” said Dironna Moore Clarke, a deputy director of the city’s Department of Public Works and head of its Office of Equitable Transit and Mobility.

That underinvestment shows up in not only a lack of sidewalks in residential neighborhoods like Bellemeade and Oak Grove, but also fewer trails and parks compared to areas north of the river.

Some of that is due to Richmond’s final, controversial annexation of parts of Chesterfield in 1970: “Developers built these neighborhoods to more rural design standards with minimal consideration for transit, walking, and biking,” notes Richmond’s Path to Equity, a plan adopted by City Council in May 2022 to help incorporate equity considerations into transportation decisions.

Correcting historic inequities

Sheri Shannon, a co-founder of nonprofit Southside ReLeaf, said historic practices like redlining and urban renewal also led to fewer investments in the city’s 8th and 9th districts, which have large Black and, increasingly, Latino populations.

“Those historic disinvestments have been because people have chosen to intentionally ignore, neglect, try to erase and push away certain populations of people within the city,” she said.

Clarke said the city has put “a really key focus on the Southside and trying to bring them up to par” over the past few years, adding miles of sidewalk and bike lanes and ramping up infrastructure like flashing lights meant to protect pedestrians from cars. In 2020, Mayor Levar Stoney announced Richmond would add five new public parks in Southside.

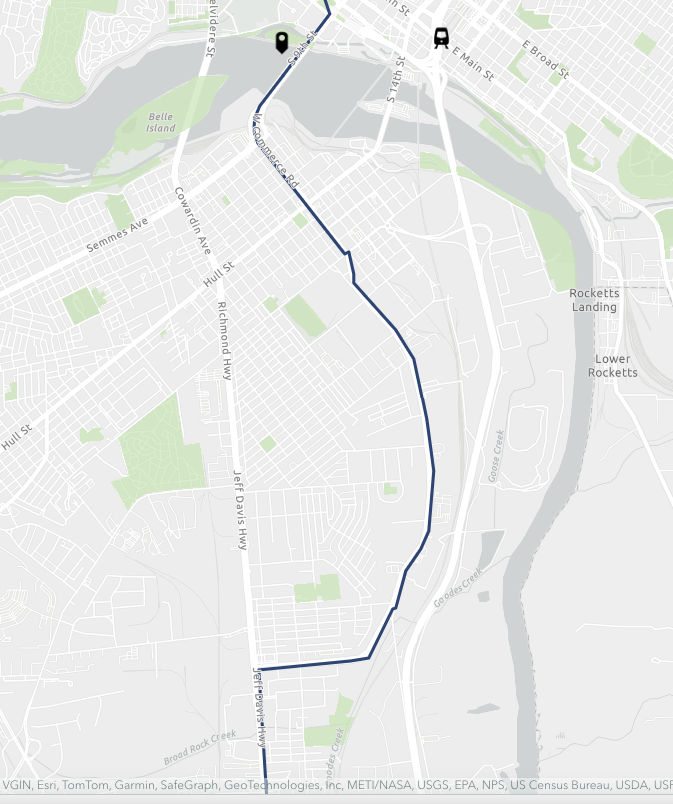

But the Fall Line Trail promises to add bike and pedestrian infrastructure to the area on a whole new scale. After crossing the Manchester Bridge, it will continue 2.5 miles down Commerce Road and Bellemeade Road — a path described as “an alternative to the area’s auto-dominated past” — before embarking on a 7-mile stretch down Route 1 into Chesterfield County.

“We have intentionally routed it to the most important places to go,” said Brantley Tyndall, director of the Bike Walk RVA program run by Sports Backers, one of the driving forces behind the Fall Line Trail’s creation. “Route 1’s future is going to look very different in 10 years.”

The goal of the trail isn’t just recreation; it’s also an attempt to provide a safer and more enjoyable transportation route for residents who don’t have a car — including children who in some cases walk to school along streets with no sidewalks.

“It is an economic driver for the region and the city,” said Shannon. “It also is a way for folks to get around to these green spaces, these other public amenities throughout the city.”

Plans for the Richmond stretches of trail show close connections to an array of community facilities, including Bellemeade Community Center, the new T. B. Smith Community Center, Summer Hill Preschool and the future Broad Creek Park — although, Shannon said, it won’t connect with most of the new Southside parks under development.

Crucially, it also will overlap with the new north-south bus rapid transit route being planned by GRTC, which will cross the Manchester Bridge before turning down Hull Street.

The trail “is really helping to make Richmond what we like to call ‘complete streets,’ where we have room on the street within our right-of-way for everybody to safely move about the city,” said Clarke.

A 'big price tag'

The project doesn’t come cheap. According to figures provided by Clarke, the Southside segments will cost upwards of $126 million, of which about half is funded. City projects tend to be more expensive than rural ones, she pointed out: Not only does land tend to be more valuable, but construction is more challenging in spaces that are already built out.

But for the Fall Line Trail, nearly everyone agrees one thing has been a game changer. The General Assembly’s 2020 creation of the Central Virginia Transportation Authority allowed local governments in the Richmond area to raise money specifically for transportation projects through the imposition of special sales and gas taxes for the first time. (Northern Virginia has had its own transportation authority since 2002.) The Fall Line Trail is the first major regional project funded by those dollars, getting $104 million from the new pot of money.

“This is a big idea, a big project with a big price tag that’s coming to fruition because of the work of a number of jurisdictions right here in central Virginia,” Stoney said at the August groundbreaking. “This type of thinking, this type of work would not be possible without people saying yes and getting to yes.”

Tyndall said the project will “pay for itself” through economic development, pointing out roughly 340,000 people live within 2 miles of the trail. Similar trails in places like Indianapolis and Atlanta, he said, are already spurring billions of dollars’ worth of increases in the value of surrounding properties.

In Richmond, where rising property values have led to some residents being priced out of their neighborhoods, those increases could be a double-edged sword.

“If this is a benefit with many assets and amenities that come along with it and Southside residents are able to use the trail and enjoy the additional investments that will come with it afterwards in a way that does not displace them, that doesn’t raise property values, that ensures that where they live right now, they can stay in their home, then yes, that is what we are supportive of,” said Shannon.