‘We’ve heard clearly that it is a priority for the community’: Bike lanes remain a sticking point on Mayo Bridge proposal

Bike lane protection — or a lack thereof — continues to be a sticking point for many Richmond officials and members of the public as plans to replace Richmond’s 113-year-old Mayo Bridge move forward.

On Tuesday, the Richmond Planning Commission agreed to greenlight a conceptual design for the bridge put forward by the city’s Department of Public Works and the Virginia Department of Transportation, which together are tasked with carrying out the project.

But over more than two hours of discussion, numerous commissioners expressed major heartburn with the early plans, and particularly their lack of physical barriers to separate two proposed bike lanes from car traffic.

“You’ve got to find a compromise for separation for bike safety,” Commission Chair Rodney Poole told engineers and planners. “I’m willing to give y’all the opportunity to do that.”

He continued: “My one vote is contingent on y’all finding something that provides the safety more than what we’ve talked about at this point.”

In replacing the Mayo Bridge, Richmond is hoping to meet several goals. The biggest is keeping the connection across the James River operational: Mayo is classified as being in poor condition, and in 2024 federal and state officials determined a full replacement was necessary.

Other aims are also at play. The bridge will be the public’s access to Mayo Island, which the city is transforming into a 15-acre public park. And its reconstruction offers planners a rare chance to overhaul a structure widely seen as dangerous in order to better incorporate non-car modes of travel like biking and walking — a priority highlighted by a streak of recent pedestrian deaths.

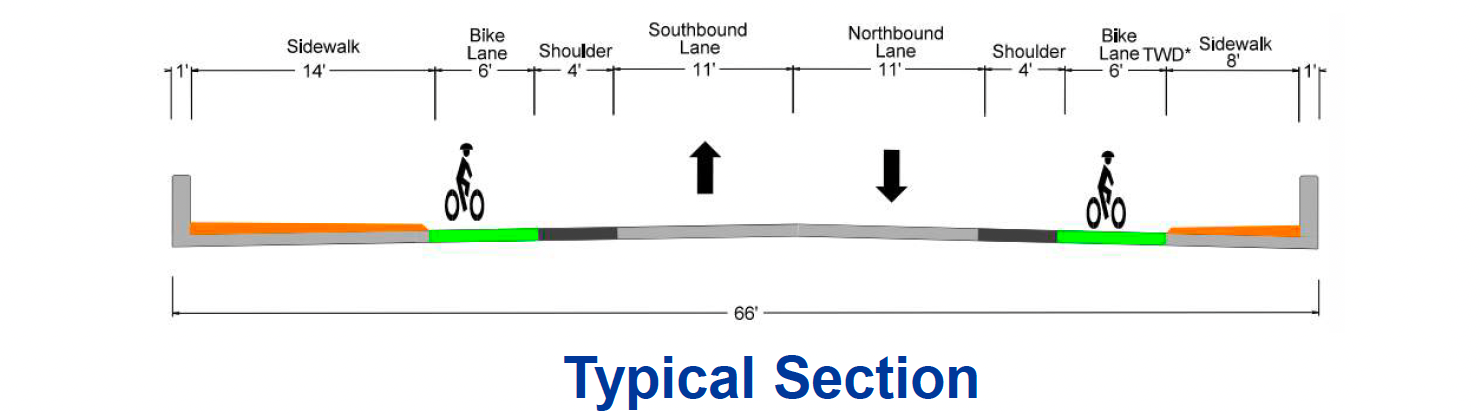

To meet all those needs, the Department of Public Works and Virginia Department of Transportation have proposed a 66-foot-wide, 25 mph bridge with two car lanes, two bike lanes and two broad sidewalks. At Mayo Island, the bridge will bend, buses will get a pull-off lane to stop and a raised crosswalk with flashing beacons will alert drivers to pedestrians who want to cross the road to access either side of the new park.

Whether bikers and pedestrians will be safe enough under that design was a question that cropped up again and again at the Planning Commission.

“The whole idea just makes me nervous as to why anyone would feel any safer than they currently feel on that bridge,” said City Councilor Ellen Robertson (6th District), who sits on the commission, at one point.

Engineers and planners have said the bridge’s bent design, lower speed limit and raised central crosswalk will significantly slow speeds, and they have promised to explore other ways of making the pedestrian crossing on Mayo Island safer.

The bike lanes, which under the conceptual design are only separated from the car lanes by four feet of painted space, have raised particular worry.

In reviewing the plans last week, Richmond’s Urban Design Committee recommended that the city and VDOT revise the plans to “incorporate low height, high contrast visible barriers for protected bike lanes.”

But the agencies have balked at that request. The Richmond Fire Department has said that any physical barriers would keep cars from getting out of the way of fire trucks crossing the bridge, which it says happens about 14 times a day. With only one lane of vehicle traffic in each direction, RFD says cars will need to be able to pull into the 4-foot buffer and 6-foot bike lane to let emergency responders pass.

“The more obstacles that you put in their place, the less likely they are to move over to allow us to proceed across the bridge,” said Anthony Jones, an RFD engineer and assistant fire marshal.

Many commissioners were skeptical. Richmond is full of narrow roads already, they pointed out; Hull Street, which lies at the bridge’s southern terminus, has little room for trucks to maneuver. Others questioned the safety of a plan that would divert cars into the bike lane.

“We’ve heard clearly that it is a priority for the community to have a separate bike lane,” said Commissioner Brian White. “I think from a safety perspective we’d risk a lot more people getting hurt by not having a protected lane than we would by not having a pullover location for this relatively short bridge.”

The UDC’s chair, Justin Doyle, said he stands by his committee’s recommendations.

“The key takeaway for me is the need to come up with a solution to separate the bike lane from vehicular traffic,” he said. “I believe there are precedents in the commonwealth that we can look to and find a solution.”

VDOT and Public Works acknowledged narrow streets exist elsewhere but said they don’t want to add even more bottlenecks into the system. And while they conceded that they are leaning toward not including any barriers, they said they would continue exploring the possibilities.

“We’re going to look into something like rumble strips,” John Kim, Richmond’s bridge engineer, told the commission as its members discussed the possibility of physical barriers. “We need to give [the fire marshal] options that they can approve. Rumble strips is one that they can approve. This one we cannot agree to.”

Despite members’ reservations, the Planning Commission agreed to approve the conceptual plan in an effort to keep the project — which requires hefty state and federal funding as well as federal review — moving forward.

They put some caveats on the approval, however, asking planners to explore an array of alternatives for various features, including the bike lanes, and requiring them to come back with a more detailed plan before seeking the commission’s final approval of the design.

“I don’t want to be back in this position months down the road where we’re being asked to give final approval and have all of these questions and concerns raised,” said Vice Chair Elizabeth Greenfield.

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org