'Un/Bound' exhibit at VMHC asks visitors what it means to be free

Nestled behind double doors on the Virginia Museum of History & Culture's main floor is a new exhibit tracing Black Virginians’ history from the commonwealth’s colonial roots to modern day.

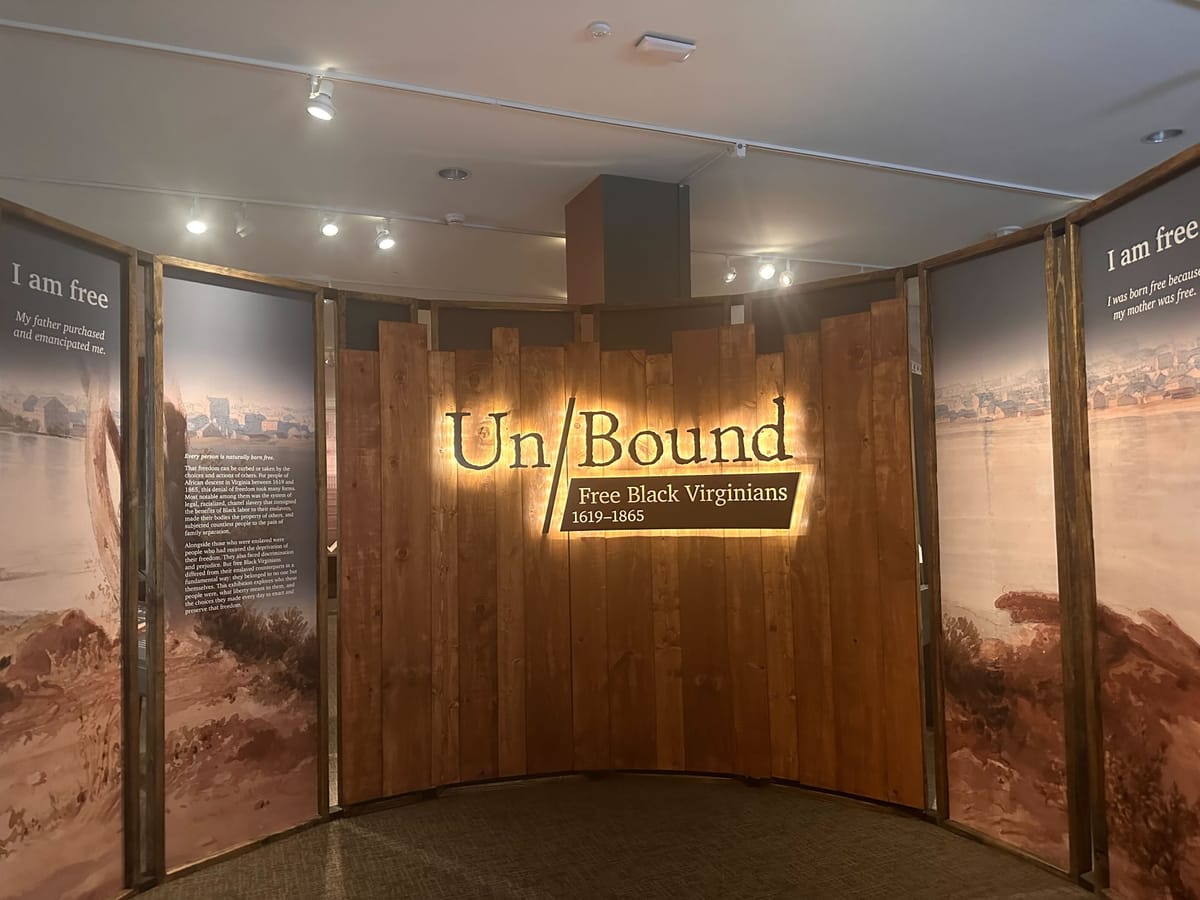

“Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619-1865” officially opens its doors to the public on Saturday after two years of development and will remain open until July 4, 2027 — an intentional date, completing the installation’s run with a focus on freedom.

Museum-goers will be greeted by the exhibit’s glowing name and will walk through a circular physical timeline starting with slavery being established as a legal institution.

Photos, artwork and scans are plastered on walls — sourced from various archives and Virginia families. Periods of time are differentiated by color and feature artifacts ranging from love letters to family heirlooms.

The exhibit’s curator, Elizabeth Klaczynski, said it was inspired by a 2021 Richmond Times-Dispatch editorial by two of the exhibit’s advisers — Timothy “Tim” Sullivan and James “Jim” Dyke, Jr. — which called for Virginia institutions to better platform Black history.

“The time is long overdue not only to tell but to highlight those stories and to recognize that Black history is Virginia history,” the duo wrote.

Sullivan and Dyke worked alongside Alvin Schexnider as the main advisers to the exhibit. Alongside Klaczynski, they wanted visitors to understand Black individuals had been part of Virginia’s history since its beginnings.

“The heart of this show is the people and their stories,” Klaczynski said.

During her research, Klaczynski said she focused on both urban and rural Virginians. She time traveled using published and archived sources from several centuries, and contacted descendants. Creating the exhibit was a collaborative process between designers, an academic committee and stakeholders.

Un/Bound's heart is its 19th century portion — the era Klaczynski said Virginia’s free Black population began establishing themselves. More people owned land, got married and founded churches.

The section hosts Klaczynski’s favorite piece: a $200 bond shakily signed by Benjamin Short, who was born into enslavement and later emancipated. Short, like many others in his position, was illiterate. Still, he learned how to sign his name on the small, now-yellow piece of paper — an act Klacynski called “an assertion of personhood.”

“If he were enslaved, he could never have done this legally,” she said. “He would have never been able to enter into a bond or any sort of financial transaction at all.”

Like Short’s bond, the featured artifacts were chosen for their ability to bring Black Virginians’ stories to life.

An eye-catcher is the large silver cup with “John Dabney” engraved on its face — also in the 19th century section. Dabney, a Richmond mixologist, was also born enslaved. Around the time the Civil War dawned, he bought his and his wife’s freedom using money he earned as a bartender. The displayed cup was awarded to him for his invention: the mint julep.

Klaczynski said these otherwise humble objects gain importance when placed into context. Artifacts and accounts ask onlookers: What does it mean to be free?

The experience ends with a glimpse into the time between the Civil War’s end and now. On the wall are glowing pictures of emancipated Virginians’ descendants — people the exhibit names “the connection between past and present,” each image captioned by their names and contributions. One featured community member is Carlos M. Brown, who chairs the Virginia Historical Society Board of Trustees.

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.

Klacznski said closing with the 21st century also reminds visitors that, even though slavery was abolished, questions of freedom remain relevant.

“It allows people to reflect on their own situation and on the world we live in today,” she said.

“We like asking questions, and then people can come and create their own answers from the information we give.”

Contact Reporting Intern Eleanor Shaw at eshaw@richmonder.org