THE NEXT 50 YEARS: Richmond’s zoning overhaul envisions a denser city. What will that look like?

In the city of Richmond, few things provoke more feelings than a vacant lot.

3000 Q Street is no exception. Once a small, one-story shop, the narrow corner lot in North Church Hill now sits empty, a rectangle of grass that neighbors have come to view as an extra spot of green in the urban landscape.

All that will soon change. This March, Richmond’s Planning Commission and City Council signed off on a plan by Baker Development Resources to transform the lot into a three-unit apartment building. Each one-bedroom, 650 square foot unit is intended, said Baker planner Alessandro Ragazzi, “to provide attainable housing opportunities to individuals increasingly priced out of the market.”

The proposal sparked a backlash from many neighbors alarmed by a recent influx of construction in the area: a three-story, 13-unit development that houses popular eatery Soul N’ Vinegar on its first floor. Two duplexes. Two new single-family homes.

“The density of our block has greatly increased, which I understand is a good thing, but Church Hill is not downtown,” said T. Maxwell Shoup, who with his wife Alayna Craig owns the property next door. Besides worries about increased trash and less privacy, parking was a key concern, especially for elderly, long-time neighborhood residents who were finding themselves forced to park farther and farther from their doorstep.

“This effort to squeeze multiple residents into small spots is just getting exhausting for members of the community that are already here,” said another resident, Amy Ferry.

But for the Planning Commission, the project was a prime example of what Richmond needs. By offering both greater density and more housing, the proposal seemed to fit neatly into the vision of the city’s future laid out in its master plan — a document known as Richmond 300 that was the product of thousands of residents’ comments and years of labor.

“This is precisely what Richmond 300 is aiming at,” said Commission Chair Rodney Poole. “It’s going to be rezoned so that it will be more dense.”

The decision, and the conflict it sparked, is one likely to be repeated again and again in the coming months. Richmond officials and the public agree more affordable housing is critically needed in the city. Many also embrace the idea that a denser city is a healthier city, one with greater opportunities, more economic and cultural activity, less need to rely on cars, and, for a government that relies heavily on real estate taxes, the potential for greater revenues.

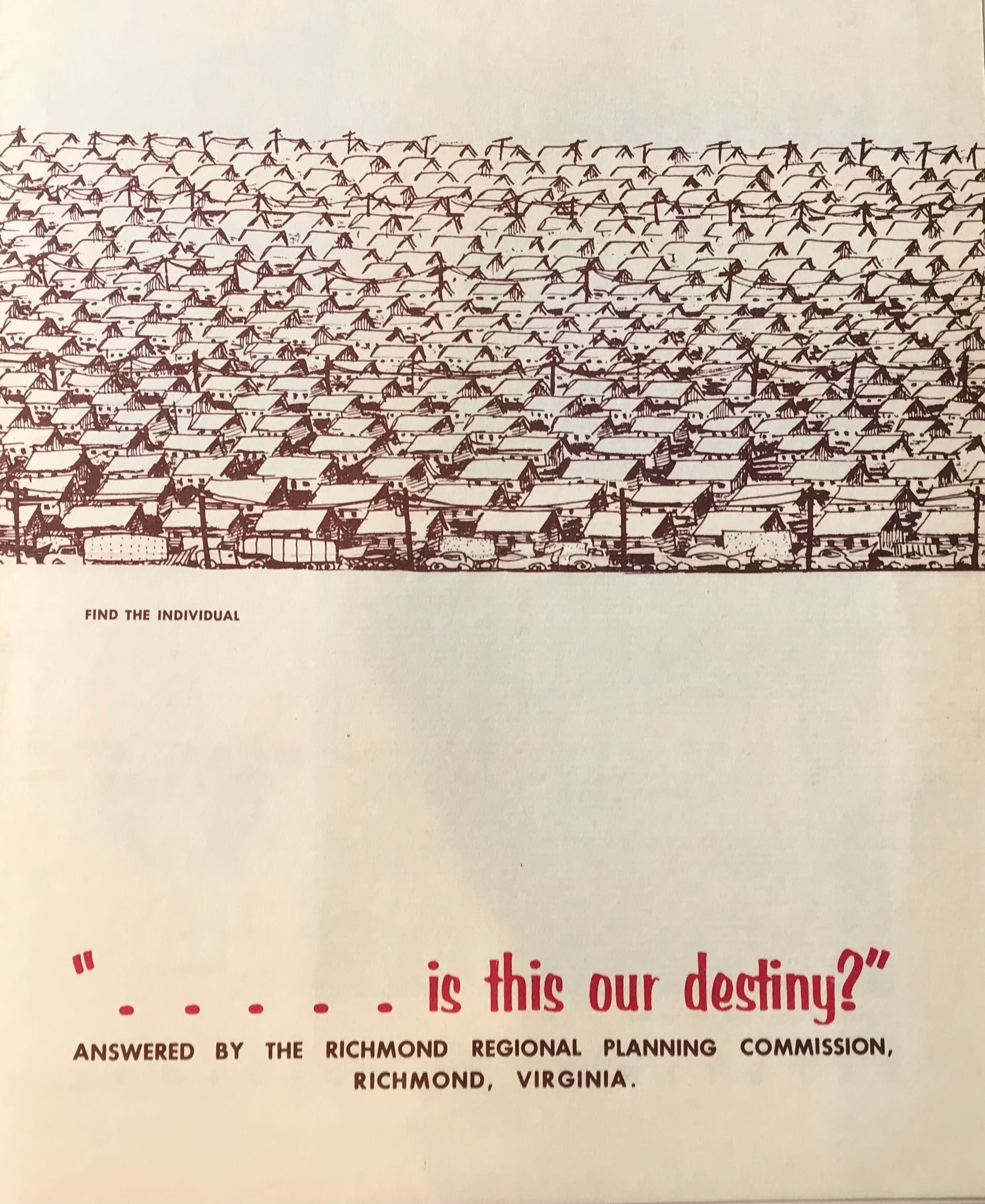

But while those ideas enjoy wide popularity in the abstract, feelings can get more complicated when the density moves in next door and residents feel its impacts in real time. It’s a possibility that many Richmonders will need to contemplate as the city overhauls its 1970s-era zoning code over the next year — a refresh aimed at not only encouraging greater density but also adapting the city’s land use rules to better reflect how people live in the early 21st century.

Richmond isn’t alone in its efforts: Chesterfield County too has undertaken a major overhaul of its zoning, which also dates back some 50 years.

“Most of this code that we have right now, this latest version, the bulk of it is majority-1970s, and it just doesn’t align with the economic, social, environmental realities of today,” said Richmond Planning Director Kevin Vonck.

So far, the Planning Department has rolled out potential new categories for zoning districts, potential new standards and what’s called a “pattern book,” a document that identifies the common elements of a neighborhood that give it its particular look and feel. Planners have organized panel discussions of the code refresh and are shopping it around for feedback at neighborhood association meetings, as well as soliciting the public’s thoughts through surveys and workshops.

The stickiest step is still to come. Citywide draft maps that will show how every address in Richmond could be zoned under the new code are expected to be released in May or June.

That, said Vonck, is “where we really need to have nuanced discussion.”

Officials acknowledge some pushback is likely. Residents in Oregon Hill have already complained about some of the city’s findings, including its determination that most of the structures in the historic neighborhood near VCU don’t conform with the current zoning code — a situation Vonck says is exactly the kind of problem the code refresh is designed to address. And the detailed maps are certain to trigger concern from at least some residents who live near transportation corridors where Richmond 300 envisions more multifamily development.

“I think people fear change, and the fear and uncertainty of ‘This is how my neighborhood has looked and felt, and now it’s going to change,’” said Elizabeth Hancock Greenfield, the vice president of government affairs at the Home Building Association of Richmond who also serves on the Planning Commission and chairs the city’s Code Refresh Zoning Advisory Council. But, she cautioned, “just because the zoning changes, it doesn’t mean your community is going to change overnight.”

Councilwoman Ellen Robertson, a proponent of the refresh who represents the city’s 6th District, stretching from Manchester in the south to Highland Park in the north, said it was important “to manage our expectations."

“Too drastic change will face opposition from people that are not comfortable with drastic change,” she continued. “I think the desire is to do drastic change, to significantly increase the zoning that allows more particularly multifamily housing, but I believe also that Richmond has such an entrenched history of such a large share of our land restricted to single-family housing that we may not accomplish the level of rezoning that I would like to see done.”

For Craig, one of the property owners next to 3000 Q Street, the fear is that in ushering in change, the city will fail to protect what is already flourishing.

“It’s so complex, because I understand what the city is trying to do for Richmond to help with our housing crisis, but I wish our city would be more thoughtful,” she said. “We do need more density, but it can’t come at the cost of established families and neighborhoods.”

A history of ‘excluding and welcoming’

The invisible hand that guides how a city grows or withers, zoning is always a fraught issue.

It determines where you can live and what kind of house you can build, where you can operate a business and what kind, whether you can have a driveway or a separate rental unit.

For almost 20 years in Richmond, it was also a tool of segregation. The city was the second in the U.S., after Baltimore, to pass an ordinance prohibiting Black and white people from living on the same block. While the U.S. Supreme Court declared that unconstitutional in 1917, Richmond took a second crack at racial zoning in the following decade, passing an ordinance that prohibited people from living on a block where they could not legally intermarry with the majority of other residents there — a ban that because of Virginia laws forbidding Black and white people from marrying had the same effect. That too was struck down.

But while the Supreme Court had quashed race-based zoning, housing segregation remained entrenched, enforced through private covenants and government-backed lending and insurance practices like redlining.

Equally as damaging in Richmond were urban renewal programs. From the 1940s to the 1970s, the city forcibly displaced thousands of residents, most of them Black, from Jackson Ward, Randolph, Navy Hill, Fulton, Shockoe Valley and elsewhere for projects including Interstates 95 and 64, the Downtown Expressway and the Coliseum.

To replace those residents’ demolished homes, the city constructed its public housing courts, the dense multifamily developments that today remain majority Black. The courts “were in specific areas, and they had really specific zoning districts,” said Vonck. They were also a world away from the majority-white streetcar suburbs made up of leafy, single-family properties that Richmond had progressively been annexing from Henrico and Chesterfield counties.

For Tom Okuda Fitzpatrick, executive director of fair housing nonprofit Housing Opportunities Made Equal, zoning boils down to a “history of excluding and welcoming.”

“Race-based zoning started in Richmond and Baltimore,” he said during a March panel on the code refresh. “That’s our legacy, and this opportunity now is to really redefine what our legacy is for the next century.”

By 1976, the year Richmond completed its last comprehensive overhaul of its zoning ordinance, the city’s population was in decline, with white residents leaving the city in droves for the increasingly suburbanized counties. Even today, Richmond is less densely populated than it was in 1950.

Zoning responded to those trends, with Richmond’s code ultimately coming to duplicate many of the suburban features homeowners then found attractive. Minimum lot sizes and required setbacks were increased, and planners attempted to strictly separate residential areas from commercial ones through restrictions and buffers.

In that vision, single-family homes were king. Today, about 59% of the city is zoned for single-family residential living. Vonck said that isn’t unusual in the U.S. — “most cities are like that.”

But for a city like Richmond, it’s a particular challenge. That’s because Virginia, unlike every other state, establishes cities as independent entities, completely separate from the counties that surround them. Elsewhere cities can tap into the land and resources of the larger counties that contain them as they grow, but in Virginia they go it alone, forced to compete with their more expansive neighbors. And while the state initially allowed cities the flexibility to annex territory from the counties as they grew — Richmond annexed land 11 times — the General Assembly put a moratorium on the practice in 1987.

With the boundaries of the city locked in place and vacant land scarce, land use decisions have become ever more fraught. Fresh surges in population have added an extra strain, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, when an influx of residents from larger, more affluent cities caused rent and housing prices to skyrocket.

The need to grapple with the housing crisis was one of the key themes Mayor Danny Avula, a Church Hill resident, emphasized during his campaign this fall.

“This push of folks from outside of Richmond coming in here has really changed the dynamic,” he said last month. “Over the years, I’ve seen a lot of my neighbors be displaced.”

Richmond “is largely built out,” said Greenfield. “A lot of our opportunity for new development does require density.”

Density and conformity

In Richmond, the poster children for density are, of course, Scott’s Addition and Manchester.

From mostly low-lying industrial areas, both neighborhoods have mushroomed over the past decade into some of the city’s densest nodes of development, packed with high-rises anchored by businesses on the ground floor and stacked with story after story of residential above. Both transformations were preceded by major rezonings that opened the door to redevelopment.

“That’s where we’ve maximized the growth potential in both of those locations,” said Robertson. But there have been tradeoffs, she acknowledged: “What we have done in that process is transform those communities to a predominantly rental community.”

The zoning overhaul underway isn’t looking to promote that kind of development everywhere. Vonck said he’s heard the criticism that “you just want everything to look like Scott’s Addition” but flatly denies that’s the aim. Instead, he said it’s intended to promote “incremental growth.”

“That does not mean apartment buildings everywhere, but it does mean probably some more apartment buildings on some more major transportation corridors,” he said.

It also could mean adjustments to minimum lot widths and sizes, maximum building heights or the number of units permitted on a lot.

The latter is one of the key questions the Zoning Advisory Committee is weighing. For years, the current code only allowed one housing unit in most residential districts. Then, in 2023, City Council voted to allow owners of single-family lots to construct an accessory dwelling unit by right. Now, the committee is weighing whether the default should become two units along with the ADU, a change that could allow duplexes in more parts of the city.

While that kind of zoning shift would encourage greater density, proponents say it won’t necessarily cause monumental ripples in neighborhoods.

“You can have density without it looking scary, because you can have that three-story multifamily unit, but it just looks like a regular two-story or one-story house from the street,” said Toccarra Nicole Thomas of urbanist group Smart Growth America at the March panel.

Backers say that would also let homeowners and developers build structures that are similar to what already exists in a neighborhood but under the current code require a special use permit to construct. The Fan is a classic example: While many of its residential lots are narrow, zoning revisions in 1961 required properties in that and other neighborhoods to be on parcels at least 50 feet wide.

In planner speak, that means the property is “nonconforming,” and when high percentages of properties in a neighborhood fall under that designation, it can signal a zoning code is out of step with the reality of what people have or want.

As the code refresh has ramped up, Planning Department analysis has found rampant nonconformity throughout Richmond, reaching to an estimated 83% in the Fan and Museum District, 82% in Oregon Hill and 68% in Oak Grove on the South Side.

“We’ve gotten special use permits in the past, and almost every time, it’s just to build something that would have been legal before 1976,” said Marion Cake, the vice president of affordable housing for nonprofit project:HOMES, which both repairs housing for low-income and elderly residents to allow them to stay in place and constructs affordable housing. “We need to get to the point where we can build stuff that looks like Richmond by right.”

City officials also say the current code restrictions are creating a glut of special use permit applications that drive up work for planners and crowd the agendas of the Planning Commission and City Council, which must sign off on each one regardless of how inconsequential it might seem.

“There are an overwhelming number of SUPs, and that’s kind of been the practice as long as I’ve been a part of the Planning Commission,” said Greenfield. “Some are necessary,” she said. Others are not.

“I am trying to get us away from these silly SUPs of building a single family [home] or building something in a neighborhood that looks just like everything else,” said Vonck. “We shouldn’t be doing those as SUPs.”

But for residents with genuine concerns about projects, the special use permit process also offers valuable protections, from mandatory notifications about what is being planned to a chance to offer comment and criticism about problems that developers may not have considered or have downplayed.

That public input can have an impact. A wave of impassioned concerns from neighborhood residents about a proposal to construct a mixed-use building at 7100 Jahnke Road has tied that project up at the Planning Commission for almost five months and spurred staff to suggest adding a condition to the permit to prohibit any sale of tobacco or vaping products. Q Street neighbors’ complaints about rising parking pressure in Church Hill North prompted Robertson to urge city officials to “pay very close attention” to how Richmond’s abolition of parking minimums plays out as density increases.

At the March meeting where the Planning Commission greenlit the Q Street plan, Commissioner Rebecca Rowe acknowledged some of the growth happening throughout the city “is not sensitive to the surroundings” and voiced the hope that the pattern books the city is producing for the code refresh could help.

On Q Street, she said, “This neighborhood has already experienced death by a thousand paper cuts.”

‘There’s so many pieces of the puzzle’

For Robertson, one of the most critical questions underpinning the zoning overhaul is simply: “What kind of city does Richmond want to be?”

That’s partly a numbers game. The University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center put the city’s population in July 2024 at about 233,000 — roughly 6,500 more people than it had in 2020 at the time the pandemic began. The region as a whole saw more than 52,000 new residents over that period. Whether those figures continue to grow or plateau out matters for planners trying to make decisions about the best uses of land.

But Robertson’s question is also about values.

“Our zoning needs to be driven by principles,” she said. In her view, one of those principles is that people of any income should have access to decent housing in Richmond, regardless of if they earn enough to buy a home in Windsor Farms or bring in only a fraction of the area median income. That means using zoning to encourage the creation of more housing.

“The bottom line is that we are pricing ourselves out of the market right now with this spike in the values of homes, and as we increase the inventory of houses, then we will position ourselves to be more competitive and be able to increase the supply,” she said. “And when the supply is increased, the demand is less, and so the costs become more equitable.”

Equity is also on many Richmonders’ minds when it comes to location. Shoup, the Q Street resident married to Craig, called it “baffling” to see multiple developments being approved in his Church Hill North neighborhood “while things like Jackson Ward remain neglected and stretches of Broad Street remain shuttered.”

Vonck said the code refresh should ideally allow for greater density all throughout the city, rather than concentrating everything in the same lower-income areas where land is cheaper and residents have fewer resources to marshal in opposition to undesirable plans.

“Everybody has to have their fair share,” he said. “In areas that are very well-serviced, let’s find some spots that allow for different types of housing in those areas. Because the land’s expensive, but it’s expensive because we’ve got grocery stores, pharmacies, transportation options.”

Despite the desire to open the door to more housing development, planners aren’t embracing every project. In recent months, the Planning Department urged the city to reject a special use permit for a 352-unit affordable housing proposal on Rady Street in Highland Park because it would remove industrial land from the city’s portfolio, although City Council approved it anyway. Staff are also urging rejection of a 180-unit affordable housing plan off Snead Road in Piney Knolls on South Side; among the host of reasons they list is that it would insert too much density into the neighborhood too abruptly and would be “located in an un-walkable, car-dependent area, far from frequent transit, employment centers, and services.”

“Part of living in a city, it's like, I need housing and I need a way to get around,” said Vonck. “There's parts of the city where sure, you can allow for more density, but if you can't get there from here, there's no sidewalks or bike lanes or transit … I'm still having other issues.”

Craig put it bluntly: In any decision, “there’s so many pieces of the puzzle to make it work.”

Still, for people like Cake, the project:HOMES developer who was part of the March panel, it’s worth trying something different.

“I think we spent a lot of the last 70 years doing exactly the wrong thing, particularly in suburbs — making all the houses the same size, all the houses the same type, thinking that that was preserving value,” he said. “But it was narrowing the market. We need to expand the market.”

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org