State will put Richmond water plant on corrective plan after review finds faulty batteries caused January crisis

Richmonders recently learned the hard way that the city’s water treatment plant is more than 100 years old.

But the city’s failure to maintain a more modern piece of technology — backup batteries meant to keep key equipment working during a power outage — was the “root cause” that allowed a relatively minor winter storm to knock out the city’s water supply for days, according to the results of a state-initiated investigation.

In a cover letter recapping the state’s findings for Gov. Glenn Youngkin and Richmond Mayor Danny Avula, State Health Commissioner Karen Shelton took an unsparing tone. She strongly implied the Virginia Department of Health’s Office of Drinking Water had overseen a more thorough and detailed investigation than the one the city released earlier this month.

“In contrast to the City of Richmond's report, the ODW investigation found that the water crisis was completely avoidable and should not have happened,” wrote Shelton, a doctor whom Youngkin appointed as health commissioner in 2023.

After state drinking water regulators found 12 “significant deficiencies” at the Richmond plant, Shelton wrote, the state intends to send the city a second violation notice and put Richmond on a corrective action plan to ensure fixes are completed. The concerns VDH identified in their follow-up visits to the plant largely deal with maintenance issues like leaks and corroded pipes, as well as “scum” observed in a finished water basin.

The state review, Shelton wrote, found a “faulty culture” in addition to faulty equipment, one in which problems were worked around or accepted as normal instead of being addressed head-on.

“DPU management and leadership allowed a complacent and reactive culture to persist,” Shelton wrote. “Known problems and flooding risks were not addressed or were allowed to exist for extended periods of time.”

Shelton ended her letter by noting the city has already made several senior management changes in the Department of Public Utilities, which operates the water plant, that are leading to more “active management and an emergency preparedness mentality.”

The Richmonder obtained a copy of the letter, dated Tuesday, as well as the 314-page report prepared for VDH by the infrastructure consulting firm Short Elliott Hendrickson Inc. The SEH report is expected to be formally released later this week.

The report identified nearly $64 million worth of upgrades the city could make at both the water plant and throughout the water distribution system. The city is already doing some of the projects identified in the report, such as replacing the batteries and automating the process of switching the plant to generator power.

Though the report found there was little that staff working at the water plant could have done differently on Jan. 6 to prevent the situation from spiraling, a lack of preparation beforehand “inadvertently amplified the risk” of the catastrophic flooding that occurred.

“General acceptance and normalization of problematic issues at the [water treatment plant] resulted in high risk for a water crisis,” the report says.

‘This aspect of the failure could have been avoided’

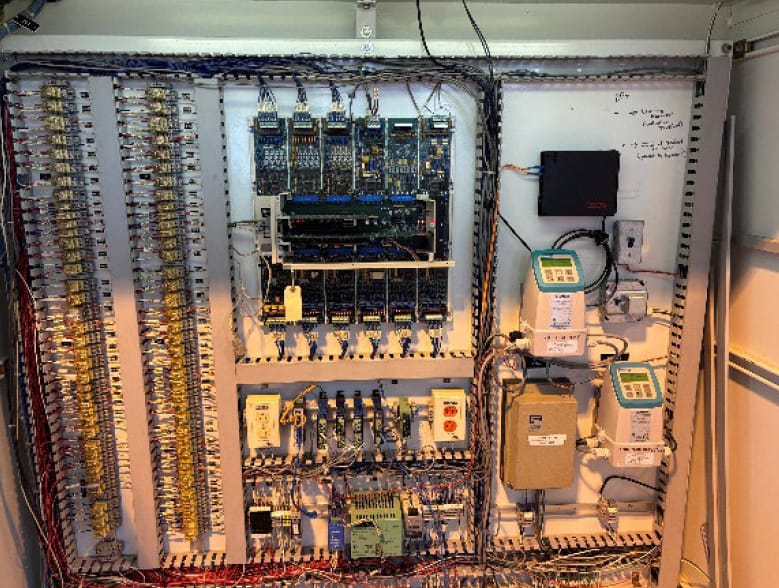

A lack of testing by the city’s Department of Public Utilities left some of the water plant’s batteries — or uninterruptible power supply (UPS) systems — in a “non-functional state” when the power outage occurred on Jan. 6, the state review found.

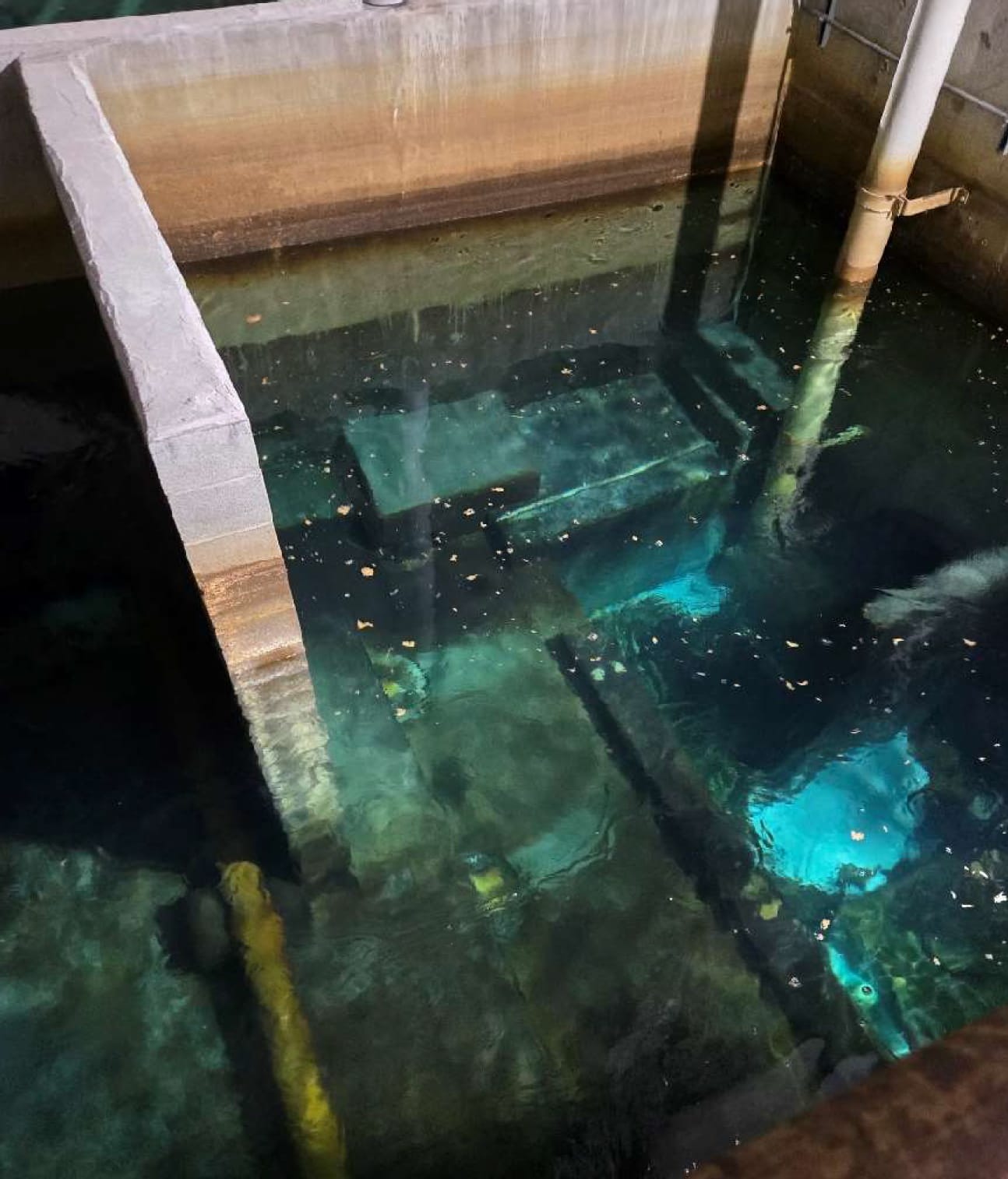

After the power loss, the faulty batteries left valves open that were supposed to close, allowing water to continue to flow into the plant’s basement. The room quickly flooded, the report says, damaging equipment severely enough that the plant lost the ability to produce treated water and pump it out to the city.

“DPU’s lack of testing and verification of the UPS system and functional testing of this failsafe was the cause of the water crisis,” the state report says.

It’s not clear what would have happened at the plant if the valves had closed in time to keep the flooding to a minimum. But with less flood damage, the plant could have potentially returned to normal operations sooner than Jan. 9, three days after the power outage hit. It took another two days of testing to ensure the water was safe to drink.

The engineering firm the city hired to conduct its own water review, HNTB, also flagged the batteries’ failure to close the valves as a key issue. However, the city’s report on the water crisis left the battery issue somewhat open-ended, saying they had failed either “due to insufficient battery power” or because of broader malfunctions with the plant’s IT and control system.

The SEH team reached a more specific conclusion. After reviewing information from the water plant system about when “bad” data signals started to appear, they determined the valves went offline “virtually immediately” instead of getting the minute or so of backup power that would have allowed them to close.

“This aspect of the failure could have been avoided with adequate preventative maintenance and testing,” the report says.

Because all batteries deteriorate over time, the report says, the city should test the batteries every six months to ensure they’ll work when needed in an emergency. Water plant staff had been relying on built-in battery health monitoring systems, but SEH said those indicators “are not always sufficient to determine when batteries need to be replaced.” The city wasn’t closely tracking maintenance work orders, the report says, which meant SEH could not determine when the batteries that failed were last replaced.

There were two previous incidents in 2021 and 2022 that should have made DPU aware there were problems with the backup batteries, SEH found, but the city still lacked an adequate maintenance plan to ensure the batteries were working and not so old they were beyond their “useful life.”

“The underlying known issue of clearwell overflow and flooding of basement is a critical failure point that DPU staff worked around for decades,” the SEH report says. “Valve operation is the critical last line of defense and the UPS did not work to close the valves to stop the flooding.”

‘This vulnerability was well known’

The SEH report doesn’t point the finger solely at the city, explaining part of the problem lies in the water plant’s basic design. Because water from the James River flows into the treatment plant by gravity, some of the plant’s key components are in underground areas. And in order to avoid flooding, water has to be pumped out as fast as it’s coming in.

“This vulnerability was well known, however, studies, reports, surveys and plans by consultants and regulators did not acknowledge or address this vulnerability,” the SEH report says. “With no external flags and historical frequency of flooding staff came to accept this as standard practice at the [water treatment plant], staff indicated they didn’t consider repair of this issue feasible.”

Modern water plants are required to have overflow pipes to avoid that problem, according to the SEH report, but Virginia’s drinking water regulations don’t require old facilities to be updated to comply with rules enacted after they were built.

The report suggested state water regulators work with the Virginia Board of Health to consider ways to “improve and update certain regulatory requirements to better address grandfathered and legacy design issues.”

The city’s water plant also wasn’t set up to handle flooding well, the report found. The flow rate the plant is authorized for means flooding can happen quickly, the report says, and the temporary pumps the city tried to use for dewatering weren’t powerful enough for the job. Water was flowing into the area that flooded at a rate of about 42,000 gallons per minute, but the dewatering pumps could only handle about 1,700 gallons per minute, according to the report.

Some of the state’s findings overlap neatly with the results of the city’s investigation.

Both reports suggest it was a mistake for the city to run the plant in a less power-intensive “winter mode” as opposed to “summer mode.” The facility normally runs on dual power feeds from Dominion Energy. In winter mode, only one of those feeds is active. In summer mode, both are active, resulting in more reliable power for the plant if one of the feeds were to be knocked out by a thunderstorm.

That decision made the plant more reliant on the switchgear equipment that failed on Jan. 6. That switch was supposed to automatically transfer the facility to the second Dominion feed after losing the first one. The automatic switch didn’t happen due to a faulty coil, but an electrical supervisor was able to complete the switch manually after the power was out for about an hour and 20 minutes.

Plant staff did not attempt to manually turn on the facility’s diesel-powered backup generators, the report says, because they felt doing so while one of the Dominion feeds was still active could cause “further damage to the electrical equipment.”

The SEH team found that the Richmond plant is overly dependent on manual processes that could be automated.

“The back-up diesel generators were useless in response to the power failure because they required manual start and were tied to the single point of failure from ‘Winter mode’ operation,” Shelton wrote as she recounted her views on what SEH found. “Had the back-up diesel generators been automatically available with both power feeds activated in ‘Summer mode,’ then the water crisis would not have happened.”

City officials have already said the plant is now operated in summer mode at all times.

State takes aim at city’s PILOT payment

The state health commissioner also zeroed in on the city’s practice of diverting some money it collects from monthly utility bills away from the water system and into the city’s general operating budget.

That type of transfer, known as a payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT), basically amounts to the city paying itself the taxes a privately owned waterworks operator would pay.

That policy has been controversial, because critics see it as a regressive way to squeeze more money out of city residents for an essential service, without investing the money back into the water system.

In her letter, Shelton echoed that criticism. If money is a factor in why the city didn’t quickly respond to all the water plant issues identified in a 2022 inspection by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, she said, the city could stop “diverting” millions of dollars from water bills away from water projects.

“ODW believes this PILOT funding could be leveraged to generate at least $80 million for recommended infrastructure upgrades,” she wrote. “ODW is aware of only a few cities in Virginia that might use PILOT as a routine practice for utility billing. While ODW does not regulate billing, a best practice would be to keep the water utility billing income within the water utility's enterprise funding.”

City findings vs. state findings

The HNTB report, estimated to cost the city around $234,000, criticized some aspects of the city’s response. But it reached less detailed conclusions than the SEH report prepared for the state at a cost of about $358,000, according to state procurement records.

“The event was caused by an equipment failure, and the effects of this equipment failure were compounded by lack of planning, lack of standard and emergency procedures and poor communication,” HNTB wrote in its report.

When HNTB representative Bob Page recently presented his firm’s report to the Richmond City Council, he said the valve problem that caused the flooding was “preventable.” But he didn’t go into detail about why the valves failed to close.

As council members pressed for an explanation of why the switchgear failed, Page said “sometimes things just fail at inopportune times.”

When City Councilor Andrew Breton (1st District) asked if there was any specific preventative maintenance the city failed to do, Page said he couldn’t talk specifics “off the top of my head.”

After the council meeting, The Richmonder attempted to ask Page if HNTB agreed with the state’s initial assessment that the water crisis was avoidable.

DPU spokeswoman Rhonda Johnson, who was walking with Page along with DPU Director Scott Morris, interjected to say Page probably couldn’t speak to the press without checking with his firm’s PR team.

The Richmonder has reached out to HNTB representatives via email and phone calls on several occasions since the city hired the company in January. The company hasn’t responded to those inquiries, and did not respond when asked if Page was available for an interview.

Contact Reporter Graham Moomaw at gmoomaw@richmonder.org