Richmond’s immigrant populations remain uneasy entering 2026

On a November drive in Williamsburg, Maria breezed down the hill of a 55 mph highway. She did not notice that her speed had increased to 70 mph. Before she knew it, a police car pulled up behind her. Scared, she listened to the police officer as he explained that he was giving her a speeding ticket.

Since January, Maria (She requested The Richmonder use only her first name due to her undocumented immigration status) has lived a life filled with anxiety. The 35-year-old and her husband work in construction, and have intentionally sought out jobs at different work sites to avoid potentially getting caught up in the same raid. A speeding ticket was the last thing they needed.

The Guatemalan couple have three children and made the voyage to Richmond in 2018. Maria traveled with her daughter through Mexico, spending 43 hours in a container with only a bottle of water as subsistence. They eventually made it to Richmond and were joined by her husband and two other children two months later. Now, worried about deportation, they limit trips outside of the house, focusing on the necessities like grocery shopping and commuting to work.

“If we go out, we don't know if we'll return to our families,” she said. “I have children here and, honestly, I live in fear every day.” She added that her children have had nightmares that she was deported.

As for the speeding ticket, Maria was grateful to learn that she did not have to show up in court and could pay the $171 fine online. It's a fear shared by many, as ICE has made arrests at courthouses in Chesterfield County and Albemarle County.

Those tactics have accompanied President Donald Trump’s second presidency. His administration has restricted asylum, declared an invasion of the U.S. by non-citizens, and sought to end birthright citizenship.

Trust policies

While immigration policy is set at the federal level, immigrant rights advocates see opportunities for local and state governments to take actions that would make life less stressful and safer for Richmonders like Maria.

Josue Castillo with New Virginia Majority is pushing for the city to adopt a “trust policy,” which would enshrine the city’s commitment to not cooperate with ICE. The City of Arlington and Fairfax County have also adopted such a policy.

“Some folks in the community don't feel safe going to court. They don't feel safe interacting with local law enforcement, calling emergency services,” he said. “They think that doing these things could put them at risk of deportation, and a ‘trust policy’ is meant to give a sense of ease to these people and let them know that the city is doing something to fight for them.”

But Castillo said he has heard from some City Council members who worry that adopting such a policy would make Richmond a target for increased ICE enforcement.

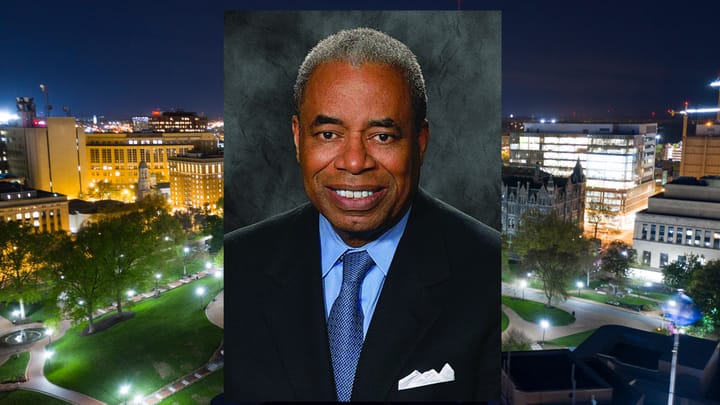

Mayor Danny Avula’s Office commented on the topic to VPM in October: “We reiterate and continue to affirm that we do not and will not coordinate with ICE on deportation. Mayor Avula and RPD Chief Rick Edwards are in lockstep in their support of local communities, and the RPD has not signed a 287(g) agreement with ICE. Officers are here to protect our neighborhoods, not to enforce federal immigration policies.”

Immigration rights advocates also hope that the transition from Gov. Glenn Youngkin to Gov.-elect Abigail Spanberger will yield better protections at the state level. In February, Youngkin signed an executive order directing state law enforcement to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement, as a part of the 287(g) program. During her campaign, Spanberger told the Virginia Mercury doing away with Youngkin’s executive order would be one of her first acts as governor.

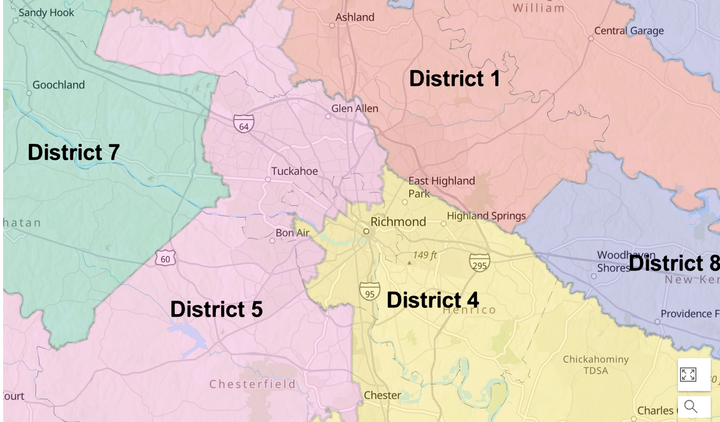

During Trump’s first term, the state did not see much participation in the 287(g) program. But it has gained momentum statewide during his second term, with 32 jurisdictions signing an agreement as of December 12.

“There's just an overwhelming, pervasive sense of fear and uncertainty, and that fear and uncertainty has really considerably grown with the collaboration between federal immigration enforcement and law enforcement in Virginia,” said Sophia Gregg, a senior immigrants’ rights attorney with ACLU Virginia.

Local impact

As for local immigration attorneys, they have seen workloads soar under the Trump administration. Dustin Dyer has been running his immigration law firm in Richmond since 2001. He said his firm’s immigration removal defense team is “super busy.” The firm went from one attorney focused on deportation proceedings in 2020 to three currently.

Trump’s second term has presented different challenges. For example, he said clients are increasingly unlikely to show up to court for removal proceedings out of fear.

“I think the administration wants people to not show up so they don't have enough time to fight their case,” he said. “They get an order of removal entered in their absence, and then at any point in the future, if ICE comes across them, they can remove them immediately.”

He has also noticed that clients don’t seem to want to go near an immigration attorney’s office. Dyer helps the City of Richmond’s Office of Immigration and Refugee Engagement put on legal clinics. Typically, there is a line of people looking to speak to him, but when he volunteered this fall he had one person show up.

“What they're trying to do is they're trying to get people to self-deport, to make life here as miserable as they can, so people just give up,” Dyer said.

But Maria does not consider self-deportation an option for her family. She sees opportunities for her children in Richmond that wouldn’t be possible back in Guatemala.

“They have a future here,” she said. “I don't want to ruin their future.”