Richmond officials say the $5.8M bill for a wrongful conviction was a surprise. But the city slow-walked a response for months

Richmond officials have suggested they were caught off guard by a recent demand to pay a wrongfully imprisoned man $5.8 million in accordance with a new Virginia law. But the city had several opportunities to engage on the matter before Gov. Glenn Youngkin threatened to withhold state funds if the city doesn’t pay, according to records obtained by The Richmonder.

On May 27, a law firm sent Richmond Mayor Danny Avula’s office an email explaining the city would have to provide a local match for the $5.8 million payment state officials had approved for its client Marvin Grimm, a Richmond man who was formally exonerated last year after being wrongly convicted for the murder and sexual assault of a child in 1976.

Richmond also had an “obligation” to pay Grimm $5.8 million, Arnold & Porter said, because of two bills approved by Youngkin after winning unanimous passage in the General Assembly. One of those bills required local governments to match the state’s compensation in cases where local police helped lock up an innocent person.

“Can you please let us know if Mayor Avula has availability to meet with us either later this week or early next week?,” the Arnold & Porter associate wrote to Avula’s scheduler, Kelsey Larus.

Larus responded two days later on May 29.

“I’m not familiar with this case so appreciate the details,” Larus wrote to Grimm’s legal team. “Sadly, the mayor’s schedule is literally back-to-back in the coming weeks but let me connect with folks on this end and will circle back with next steps.”

With no further response, the law firm sent two more emails on June 3 and June 11.

A more formal letter followed on June 17, addressed to both the mayor and City Attorney Laura Drewry. The state was planning to pay its $5.8 million when the new laws and new budget took effect July 1, the letter said, and Grimm’s team asked what Richmond’s plans were. A city official confirmed receipt of the letter, without giving an answer on the money.

In a fourth email to the mayor’s office on June 23, the firm stressed that “July 1 is quickly approaching.”

After waiting until late July, Arnold & Porter asked Youngkin to help by using his newly granted power to withhold state money from localities that refuse to compensate wrongfully convicted people. That enforcement power was built into the legislation passed this year for the express purpose of forcing reluctant local governments to pay wrongfully incarcerated people.

The mayor’s team shared the Arnold & Porter inquiries with the city attorney’s office, according to the city, and apparently deferred to the attorneys’ legal advice.

“While we did respond to the May communication from Mr. Grimm’s counsel, we understand that delays in additional responses have been frustrating,” a city spokesperson said. “Nevertheless, we are committed to appropriate restitution for this deeply troubling case.”

The governor quickly complied with the request to pressure Richmond to pay. Youngkin sent Avula a strongly worded letter on July 25 — nearly two months after the law firm’s initial email to the mayor’s office — that said the city must pay Grimm by Aug. 15 or risk losing state funds.

The governor’s letter (and the news coverage that followed) got the city’s attention. But Richmond officials are still scrambling to figure out how to proceed. And they’ve struggled to explain how they were caught flat-footed by legislative action happening in public right across the street from City Hall.

In a brief interview Wednesday, Avula said the governor’s letter “felt like it came out of nowhere.”

The city is still trying to understand the nuances of the new law, he said, and what Richmond’s “appropriate response” should be.

“Nobody in the General Assembly ever brought this up with us,” Avula said. “The lobbyists never brought it up. The delegation never reached out.”

When the mayor was asked if the city intends to pay Grimm some amount of money, his Press Secretary Mira Signer interjected.

“I don’t think we really know,” Signer said. “You know that the mayor cannot spend any money unless the City Council gives permission. That’s the normal course of action.”

Avula said officials were still exploring whether a payment to Grimm could be covered by the city’s liability insurance. But according to the early research, he said, the city would probably have to come up with the money from its own funds.

The City Council also just learned about the financial obligation recently, and some members are frustrated they weren’t looped in earlier. In an interview, Councilor Reva Trammell (8th District) questioned why the city attorney’s office didn’t deal with the situation sooner or make Council members aware of it.

“I think they should pay it,” Trammell said. “But where do we find the $5.8 million?”

The city attorney, who is appointed by the City Council but oversees legal strategies for the city as a whole, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

An auto-reply email said Drewry is out of the office until Aug. 13, which is two days before the governor’s deadline. (UPDATE: The city has set a meeting and committed to making the payment.)

‘Any localities want to speak on this?’

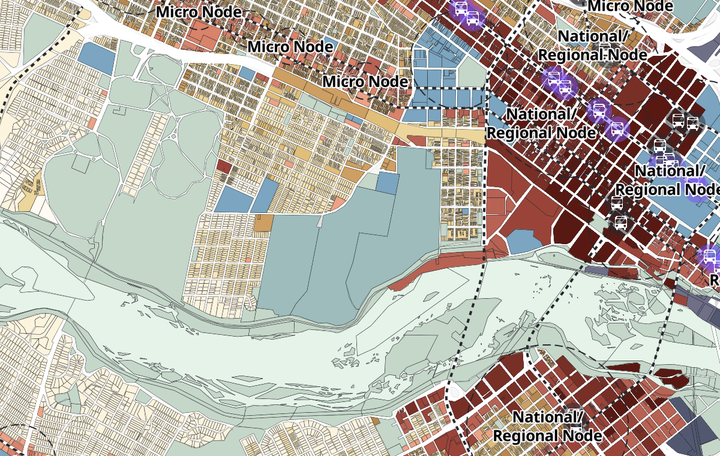

Grimm was convicted for the alleged murder and sexual assault of a 3-year-old boy whose body was found in the James River after he disappeared from an apartment complex. Grimm lived in the same complex, and became a suspect in the case because of neighborly disputes he had with the boy’s family.

Grimm confessed to the crime and entered a guilty plea, but later said he only did so after being interrogated to the point of exhaustion and being incorrectly told he could get the death penalty if he didn’t admit to killing the child. He was paroled in 2020, and successfully pressed his innocence claim thanks to new DNA testing that undercut key evidence in the case and a more modern understanding of false confessions.

With so much of the hard evidence in the case nullified, the Virginia Court of Appeals ruled that the state was left only with “a body and a man claiming responsibility without accurately describing any of this case's facts.”

Until 2020, Virginia law barred people who had pleaded guilty from filing court petitions seeking to prove their innocence based on new biological evidence.

Grimm’s case is the longest wrongful incarceration in Virginia history, which partly explains why the sum he’s been granted by the state is so large.

Though city officials have yet to discuss the Grimm matter in a public meeting, there appears to be some frustration that state policymakers enacted a law that creates major financial impacts for local governments without building in any advance notice or giving localities a window of time to budget for the expense.

Councilor Stephanie Lynch (5th District), said the new law might need some tweaks going forward, but she supports the intent behind it.

“I think we have to have a discussion maybe next year about how to plan for this in our own city budget,” Lynch said. “Or talk to our General Assembly members to create some type of flexibility on the payment date so that it is aligned with our local budget.”

Officials also seem to be exploring whether there was an equal amount of state and local culpability in the Grimm case that would warrant an even split in paying him for the decades of freedom he lost. The law mandates equal payments from the state and locality, so it’s not clear how the city could resist paying without challenging the law in court.

Given the fiscal constraints the capital city is under due to the large amount of tax-exempt property in Richmond owned by the state, it will probably be more difficult for Richmond to find $5.8 million than it was for the state’s budget-writers.

It’s not lost on some city officials that the General Assembly is effectively ordering Richmond to come up with millions of dollars after the same officials ordered VCU not to pay Richmond $56 million the city felt it was owed in the fallout of a botched VCU Health development deal.

Though city officials may have quibbles with the law as written, Richmond’s representatives didn’t appear to be closely tracking the legislation during the General Assembly session earlier this year, when there were numerous opportunities to seek revisions or raise objections.

“Is there anybody opposed to the bill? Any localities want to speak on this?,” Senate Majority Leader Scott Surovell, D-Fairfax, said at a committee hearing in February. “OK, doesn’t look like it.”

With no opposition raised at that hearing or others, the bill cruised through the legislature with bipartisan support for the idea of maximizing compensation for people mistreated by the criminal justice system.

A Richmond lawmaker — Democratic Del. Rae Cousins — was a co-sponsor of the bill that created the financial obligation for the city.

In a statement, Cousins said she supported the bills related to Grimm because “wrongful incarceration destroys lives and families.”

“I recognize the difficult financial position that the city currently faces; however, the city, as well as the Commonwealth, has an obligation to right the wrongs of the past and fairly compensate Mr. Grimm,” Cousins said. “I am happy to be part of any discussions to resolve this difficult situation."

The bills were mostly spearheaded by Del. Rip Sullivan, D-Fairfax, who said he too thinks Richmond should pay Grimm as the revised law requires.

Richmond’s delayed effort to grasp the implications of the new law has created clear risks to the city. In addition to the governor’s threat to dock Richmond’s state funding, Grimm’s legal team has said he’s reserving the right to sue the city until Richmond confirms it will pay.

The delay and unresponsiveness have also created an awkward political dynamic for the city, making a tough-on-crime Republican governor appear more eager to right a law enforcement wrong than a heavily Democratic city with more progressive views on criminal justice.

It’s not clear how long Richmond can continue to think things over before either Grimm’s attorneys or Youngkin take additional action.

The correspondence obtained by The Richmonder shows Grimm’s legal team contacted the city as far back as December, before the General Assembly session had begun.

On Dec. 16, Arnold & Porter sent the city a notice of claim, a legal notification that’s often a precursor to a lawsuit or negotiations about a financial settlement.

Deputy City Attorney Wirt Marks sent a brief reply indicating the city was referring the matter to its third-party legal claims handler “without waiving any defenses.”

Though the city received that notice in late 2024, the possibility of paying Grimm didn’t come up in the city’s 2025 budget talks.

Even if city representatives didn’t have a full understanding of the immediate budgetary impact from the pending law, it didn’t go unnoticed by the local media.

In late March, the Richmond Times-Dispatch published an article about the new state law requiring the city to pay Grimm $5.8 million.

“While Richmond tightens its belt to take on potential financial losses, it will also be asked to pay millions of dollars to deal with a skeleton that has come out of the prosecutorial closet,” read the first paragraph of the article written by reporter Luca Powell.

The city budget wasn’t finalized until mid-May.

Contact Reporter Graham Moomaw at gmoomaw@richmonder.org

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.