Richmond cuts 200 seats in Head Start program as it struggles to get eligible families to enroll

Richmond will have 200 fewer slots next year for children to enroll in Head Start and Early Head Start, the nation’s preeminent early childhood education and care programs for low-income youth under the age of 6.

While President Donald Trump’s administration has recently floated plans to defund Head Start nationwide, the Richmond decision is being driven by a more local problem: persistent underenrollment.

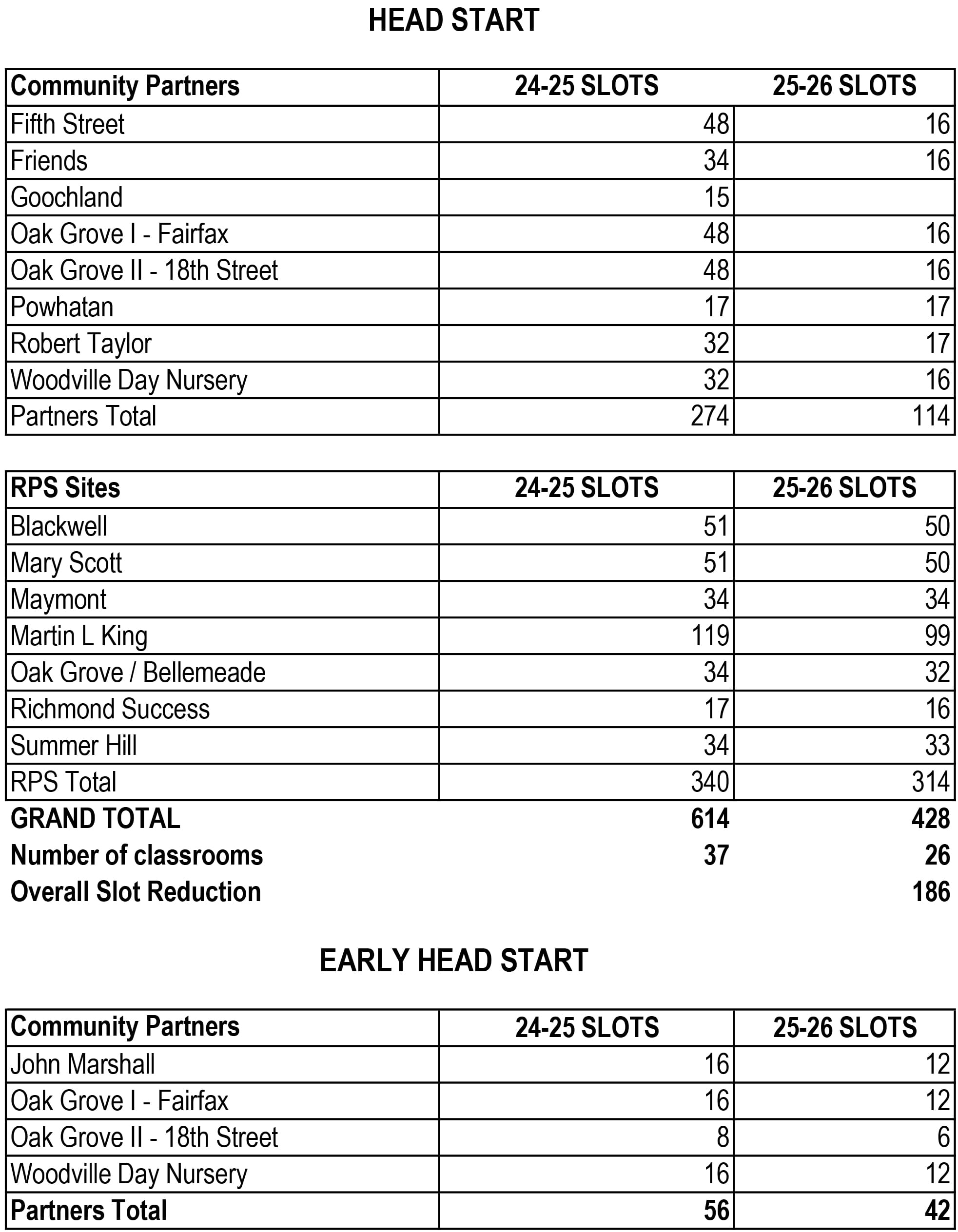

Although Richmond’s Head Start program, which is managed by Richmond Public Schools, has 614 slots available for children this year, its average enrollment is only 503. The situation is similar with Early Head Start, a companion program that serves children under the age of 3: Of 56 slots available, only 44 are filled on average.

For the School Board, that situation poses an immediate existential problem. Because the federal government requires all Head Start programs to consistently fill nearly every seat it funds, low participation will eventually trigger funding cuts.

“We’re at risk of losing the grant altogether if we didn’t take action,” said School Board Vice Chair Matt Percival (1st District) after an April 28 vote on where specific slots would be cut. Board member Stephanie Rizzi (5th District) echoed that view: “We had no other choice,” she said.

RPS has cited a range of reasons for why it has struggled to fill the program’s seats. Among them are transportation gaps, child care worker shortages and competition with other programs that have less rigorous rules than the highly regulated Head Start. The plan it has put forward to reduce seats would reallocate funding to improve worker pay as well as transportation.

But with thousands of children in Richmond eligible for the program — just under one-fifth of the city’s population lives in poverty, according to U.S. Census estimates — some child care and education providers say the persistent underenrollment indicates RPS needs to significantly change how it’s managing the program.

“We should not be doing this to ourselves,” said Rupa Murthy, CEO of YWCA Richmond, which offered Head Start seats for decades until they were eliminated under another 100-seat cut approved by the School Board last year. “It’s not as though you can’t enroll families. It might just be you can’t enroll families the way RPS has been working to enroll families.”

A spokesperson for Mayor Danny Avula, who during his campaign last fall called for the city to “support and strengthen” its pre-K programs like Head Start and Early Head Start, said in a statement that his office was “monitoring the School Board’s decision on this important matter.”

“We continue to believe in the incredible social-emotional and cognitive benefits that Head Start and Early Head Start programs provide,” wrote Mira Signer. “We recognize that these and other health and human services programs play a really important role in supporting Richmond’s families and children.”

What is Head Start?

Head Start was created in 1965 as part of former President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Besides providing free preschool education, the taxpayer-funded program offers medical care and screening, nutritional guidance and family services to children ages 3 to 5 whose families are at or below the federal poverty level, are receiving other forms of public assistance or are part of the foster care system. In 1995, Congress expanded the program through the creation of Early Head Start, which works with children from birth to age 3.

While Head Start and Early Head Start are overseen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, they are administered locally by thousands of organizations around the country, many of whom partner with other groups.

In the Richmond area, Head Start was initially overseen by the Richmond Community Action Program (now known as the Capital Area Partnership Uplifting People, or CAPUP) but is now managed by Richmond Public Schools, which is also responsible for classrooms in Petersburg as well as Goochland and Powhatan counties.

High need, low enrollment

Data indicates thousands of Richmond children are eligible for Head Start and Early Head Start.

One presentation from Richmond Office of Children and Families Manager Eva Colen to a City Council committee this February estimated the city has over 5,700 children living below the federal poverty level who are under age 5.

Head Start and Early Head Start aren’t the only way to serve them; both the state’s Virginia Preschool Initiative and Mixed-Delivery Program, as well as the Child Care Subsidy Program, provide financial assistance to families.

But Head Start has been around longer, is more widely known and offers more services than its counterparts, features that have garnered it a passionate following of supporters who for decades have seen it as one of the most effective tools for putting children on a path out of poverty.

“Head Start does a lot of things behind the scenes that people just aren’t aware of,” said David Young, executive director of the FRIENDS Association for Children, which operates two Head Start and Early Head Start centers in Church Hill and Jackson Ward that next year will see their seats halved, from 66 to 33.

Despite the need, Richmond has struggled to get children into its programs. In that, the city is in stark contrast to Petersburg, whose program it also oversees. While Petersburg’s average enrollment sits at 99.5%, Richmond Head Start is at 84.9%. Early Head Start hovers at just under 80%.

“We know, especially in the areas we operate, that the need is still out there,” said Young. “So what is the problem making a connection with these families?”

Limited transportation

No one has a firm answer for why enrollment in Richmond is so poor. RPS points to multiple factors, ranging from a lack of transportation to partner centers, worker shortages, greater competition from other programs with fewer requirements, population shifts and “parent preference for other preschool options.”

Others say those factors are real but that enrollment won’t improve unless RPS works more collaboratively with partner organizations to come up with solutions to the challenges the program is facing in Richmond.

“We need partners, and we hope that RPS understands that too,” said Murthy. “We have to figure out how to build that trust within our education system and our district.”

Where the vacancies are occurring may be indicative. Many of Richmond’s empty seats are in classrooms run by community partners. That means that most of the slots being cut next year — 174 of the overall 200 — will come from these organizations.

Providers have limited control over that situation. Richmond’s enrollment process is done through RPS, which then matches children to particular classrooms based on their location and preferences.

Transportation is a particular chokepoint, say many providers and parents. Head Start regulations require that children be moved via school bus or similar vehicle, and mandate the use of child restraints and bus monitors. But while RPS provides transportation for children who attend classrooms at its schools, it does not for classrooms at sites run by community partners.

That “has made it very difficult to enroll families for reasons that are perfectly understandable,” said Superintendent Jason Kamras. “If you are very low income and you don’t have a way of getting to the partner sites other than public transportation, it can be a disincentive for you to participate.”

Kamras has pledged to provide transportation to the non-RPS centers next year. That can be accomplished, he said, because while the division’s application reduces slots, it doesn’t reduce funding, meaning money can be routed in new directions.

Pay pressures

Salaries for Head Start workers are also likely playing a role in depressing enrollment. Without steady teachers, classrooms cannot be staffed. Nationally, turnover among Head Start staff has been rising, a trend the federal government concluded in 2024 was being driven by “low wages and poor benefits.”

Right now, none of the reimbursements made to child care providers for children enrolled in Head Start “cover the actual cost” of the programs, said Young. Furthermore, increasingly competitive salaries offered by Richmond Public Schools have caused the pay gap between staff in RPS classrooms and staff at partner centers to grow.

The division says decreasing slots will let it increase reimbursements from $654 to $820 per month for every Head Start slot and from $1,027 to $1,052 for every Early Head Start slot.

Kamras has also said those bumps will bring RPS in line with a 2024 federal mandate that will require Head Start programs to ensure workers earn salaries that “are at least comparable to those of preschool teachers in public school settings” while also providing better benefits and “wellness supports.”

But the speed of the increase has caused some concern. None of the new mandates go into effect until 2027; the salary requirements don’t have to be in place until Aug. 1, 2031. Programs will also have the option to ask for a waiver in some circumstances.

Kamras acknowledged RPS has several years to meet the mandates but said the School Board and the Head Start Policy Council, a group of parents and community members who help guide local programs, wanted to “rip the band aid off” all at once.

“My sense of how the Policy Council and the School Board were thinking about this is that to put ourselves in the best possible position with the Head Start office would be to meet the requirements as soon as possible and get the enrollment north of 97% as quickly as possible in an effort to prevent any more draconian measures such as not getting the funding,” he said.

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org

List of reduced slots: