Richmond, Bermuda are forever linked through a momentous storm

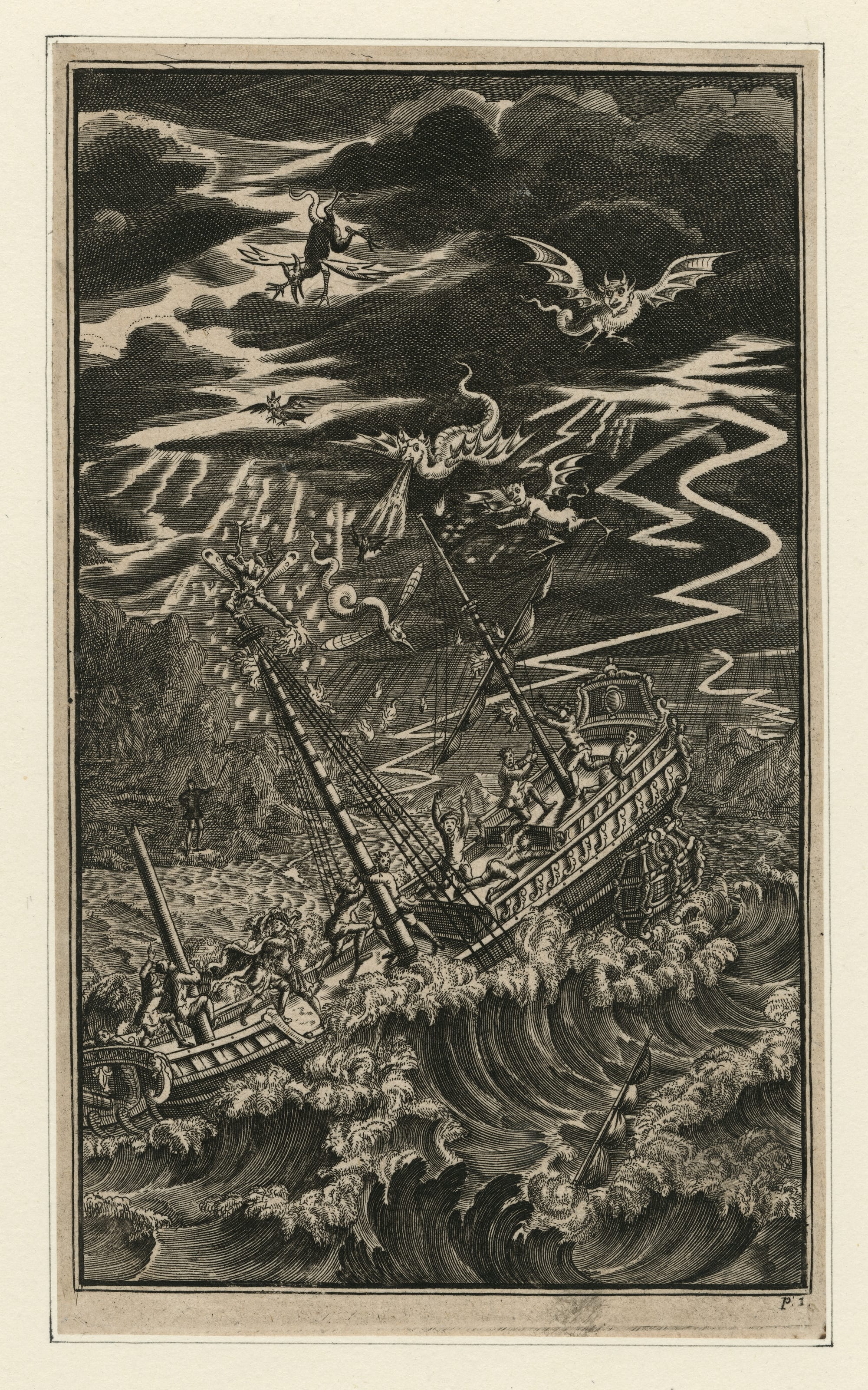

The sky turned black as the storm gained strength.

For weeks, the Sea Venture had enjoyed clear skies and smooth sailing, but the ship’s luck began to change on July 24, 1609. Part of a nine-vessel fleet sent to resupply the fledgling Jamestown colony, the Sea Venture was the 300-ton flagship of the Virginia Company of London.

Typically, European ships destined for North America at that time headed south to the Canary Islands, hung a right, then used the westward mean direction of the wind to carry them to the West Indies. But with the Canaries firmly in the grip of the dreaded Spanish, the fleet took a more direct route to Virginia. While they managed to avoid the Spanish, the new course put them directly into the heart of a hurricane.

On July 24 and 25, the rain and wind steadily grew stronger, and massive, menacing clouds filled with lightning closed in on the fleet.

In the squall, the Sea Venture was separated from the rest of the flotilla. The waves were so tall they reached the ship’s topmast. Over and over, the Sea Venture struggled to crawl up mountain-sized waves only to flounder at their crest then slide down the other side. The steersman struggled to keep the ship from capsizing. Below deck, fearful colonists tried to brace themselves as slop buckets spilled over and floors were slicked with waste and vomit.

For four days the Sea Venture was caught in the terrible storm before wrecking on a reef in Bermuda. The otherwise uninhabited archipelago offered the wreck’s survivors a chance to recuperate and construct two new vessels to complete their voyage.

Their efforts saved Jamestown, the first enduring English colony in North America. They paved the way for Bermuda to become a British Overseas Territory. They also likely inspired William Shakespeare to write “The Tempest.”

Through storms and Shakespeare, Virginia holds a unique connection to this land of pink-sand beaches, dark ‘n’ stormy cocktails and shorts worn as business attire. Here’s the story of how a fateful tempest started it all.

The Isle of Devils

The Sea Venture began coming apart.

In the 17th century it was common for ships to be made from long planks of wood that were held together by caulking called oakum. Usually made from tarred fibers of unraveled rope, oakum was packed into a ship’s joints to make a vessel watertight. The practice usually worked well to seal a ship, but it was no match for the storm’s pounding. The Sea Venture began taking on water.

William Strachey, a widely traveled passenger who chronicled the voyage, said the storm was incomparable to anything he’d ever seen before: “Winds and seas were as mad as fury and rage could make them,” he wrote. He expected that the ship would either capsize or split apart.

Those aboard witnessed St. Elmo’s fire, a weather phenomenon where an electric blue plasma discharge can be seen with the naked eye, dancing atop the masts.

After four days of the passengers and crew fighting for their lives, Sir George Somers, the admiral of the company, spotted land. The crew attempted to steer the ship through the offshore reefs surrounding Bermuda but became lodged in the shoals. Eventually, 140 men, 10 women and one dog were taken ashore in boats.

Among the survivors were ship’s Captain Christopher Newport, arriving Jamestown Governor Thomas Gates, John Rolfe, a Powhatan emissary named Namontack and his companion Machumps.

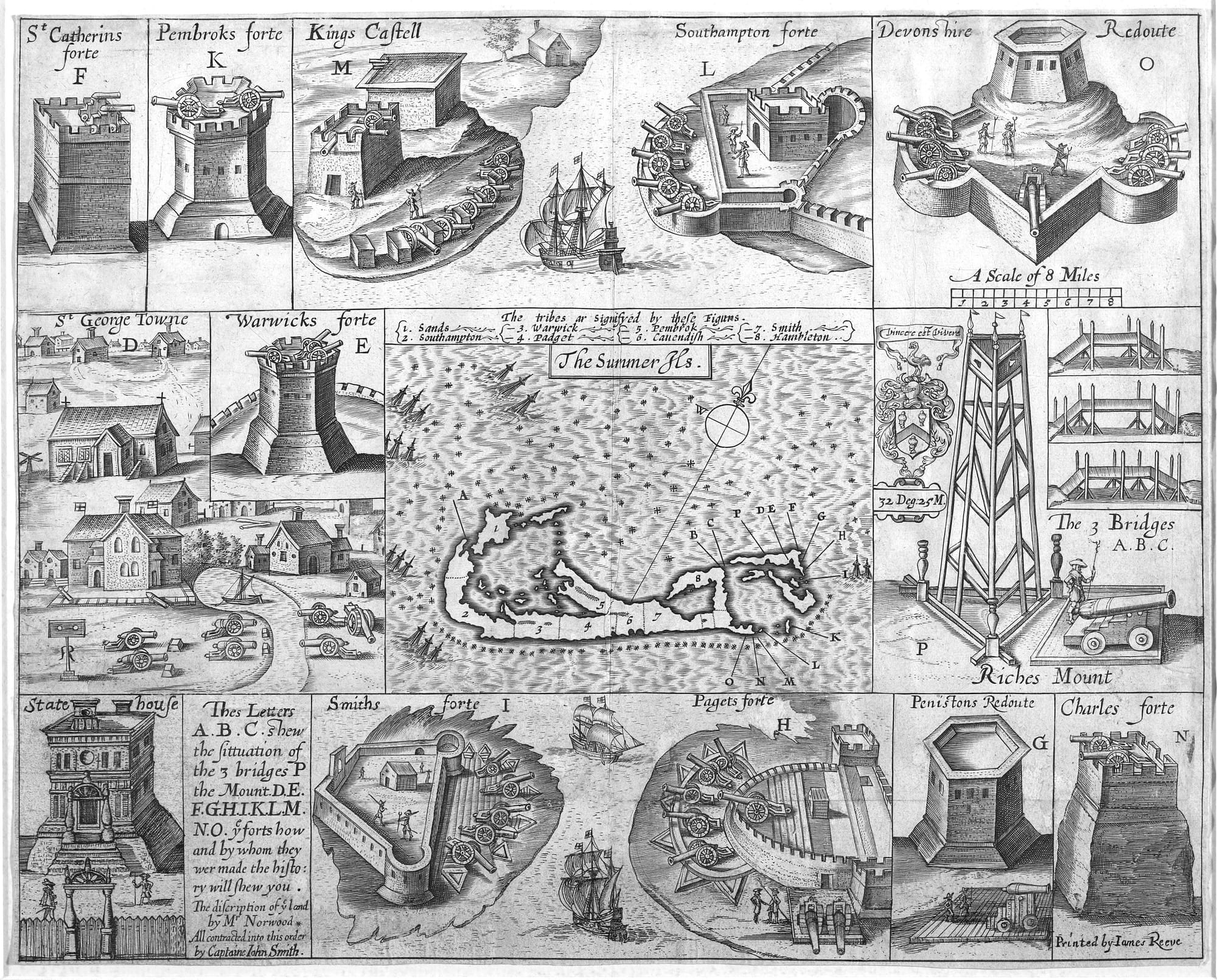

At that point, Bermuda was an uninhabited but known point on the map. It was first discovered by Spanish explorer Juan de Bermúdez in the early 1500s; legend held that the archipelago was the home of devils and spirits, likely because of the noises made by its raucous birds — known as petrels or cahows — and wild hogs. Because of the island’s sounds, frequent storms and dangerous reefs, Bermuda was known as the Isle of Devils.

“Everyone thought it was a haunted island,” said Bly Straube, senior curator at Jamestown Settlement and the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown.

To the survivors’ surprise, Bermuda was an idyllic land with abundant fish and birds to eat. As some of the survivors had heard by now about the rough conditions that awaited them in Jamestown, attempts were made to stay in Bermuda and establish a new government. The settlement became a prison labor camp as the leaders of the Virginia Company forced the survivors to build two new ships, the Deliverance and the Patience. They continued their journey to Jamestown on May 10, 1610.

Still, two troublemakers wished to stay behind. The sailors were allowed to remain and provided a small amount of rations. It was the beginning of Bermuda becoming a permanent British settlement.

‘A really fantastic place’

Modern-day Bermuda is an escape for the well-to-do.

An archipelago of 181 islands, Bermuda has a tropical climate of warm winters and hot summers. It’s known equally for the friendliness of its people as it is for being one of the costliest places on earth; the high standard of living, lack of space and high import costs contribute to this reputation.

Adam Scott wants more people to experience this luxurious paradise. On Sept. 1, 2023, Scott’s BermudAir airlines began offering “boutique” flights to Bermuda from airports in America and Canada. A two-hour route between Richmond International Airport and Bermuda’s L.F. Wade International Airport launched last June.

“It’s really a tight-knit, charming community,” said Scott of Bermuda in a June 2025 interview for this story. “It has sophisticated hotels; it has sophisticated dining. There’s a lot of natural beauty to be seen: crystal caves, pink sand beaches. We’ve got the benefit of a railway trail that stretches the entire island. Some of the best snorkeling in the world. It’s the northernmost coral reef in the world. It’s a really fantastic place.”

Having previously worked in banking for Goldman Sachs in London and Moscow, Scott is a prolific traveler. Of the more than 100 countries he’s visited, Scott says Bermuda is his “favorite place on Earth.” He created the airlines out of a desire to make it easier for people to visit the archipelago by flying directly.

“From the moment you get on the aircraft to the moment you land, you’re already experiencing the hospitality of Bermuda, the warmth of Bermuda, the smiles of Bermuda — but also the taste of Bermuda,” said BermudAir’s founder and CEO; complimentary dark ‘n’ stormys, the rum and ginger beer cocktail that was invented in Bermuda after World War I, are served aboard the airline’s planes.

Last month, BermudAir ceased that route, ending the only international offering of Richmond’s “international” airport. According to one news report, the route cancellation was a result of “a shift toward more strategic, higher-demand markets.”

Asked for comment, a spokeswoman with BermudAir sent the following statement: “Like many airlines, we’re responding to global economic uncertainty and shifting market conditions that are impacting travel demand. These schedule adjustments are part of our ongoing effort to operate a sustainable and resilient network. We continue to work closely with Visit Richmond and Richmond International Airport regarding potential opportunities. We are grateful for the warm welcome we received and would be open to revisiting opportunities there if conditions allow.”

Cannibalism and cahow bones

The survivors of the Sea Venture wreck were shocked by the conditions they found in Jamestown when they arrived on May 23, 1610.

The winter of 1609-10 is famously known as the “Starving Time” at Jamestown as the colony was contending with multiple misfortunes.

Provisions had been lost in the storm, relations with Native Americans had deteriorated to the point where the groups were raiding each other, and the wells had run dry. Some Jamestown colonizers had deemed themselves “too gentlemanly” to do farm work and neglected the crops. According to a modern-day tree ring analysis, the settlement of Jamestown coincided with the worst dry spell to hit Tidewater in eight centuries.

When he approached a group of Powhatans to trade, acting colonial president John Ratcliffe was captured and flayed with mussel shells until he died; he was tied to a stake and forced to watch as pieces of his skin were thrown into a fire. Some settlers ate insects, then the horses, then each other. One man was accused of murdering and butchering his wife.

“Terrible shape,” said Straube of the conditions at Jamestown. “They had burned their houses for firewood. The front palisade gate was broken. Everything was in disrepair.”

This was the scene that greeted the survivors of the Sea Venture. Of Jamestown’s roughly 500 original settlers, about 60 were left when the Sea Venture survivors arrived; those who remained looked like walking skeletons. The supplies transported by the Sea Venture survivors’ ships Deliverance and Patience — including salted petrel and pork from Bermuda — helped revive some of the Jamestown colonists.

“The arrival of the Sea Venture crew castaways did help revitalize those who were left, but they were still in desperate shape,” Straube said.

The colonial administrators decided to call it a day. On June 7, 1610, everyone alive boarded ships to set sail for England, relegating Jamestown to the same fate of the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke from two decades earlier.

But upon reaching open water, the colonizers unexpectedly found an English fleet. Thomas West, Baron De La Warr — for whom Delaware is named — was arriving with a last-ditch supply effort for the colony. De La Warr convinced them to turn around, and Jamestown became the first permanent English settlement in the Americas.

Taking charge, De La Warre told the settlers to cleanse the fort, which meant sweeping all surface debris into any available hole in the ground. This effort has proven invaluable for archaeologists like Straube.

“We can date these filled pits to a three-year period of time, which is unheard of in archaeology,” said Straube, who was part of the team of archeologists who found the long-lost James Fort in the mid-1990s. “Usually you’re saying a quarter century, but we can say that the material in these De La Warre-filled fissures dates from 1607 to 1610.”

Cahow bones, sea turtles, tropical fish bones, Bermuda limestone and the cannibalized remains of a young woman were found among the debris.

In the interest of reviving the colony, an authoritarian system of government was imposed upon the return to Jamestown. Enacted by Deputy Governor of Virginia Thomas Dale, “Dale’s Code” prescribed capital punishment to anyone who endangered the colony through theft or other crimes. Punished under the code, one oatmeal thief was tied to a tree and left to starve; a pregnant woman miscarried after she was whipped for “sewing shirts too short.”

Dale’s Code was replaced in 1619 by the founding of the Virginia General Assembly, the first elected assembly based on a European model in the New World and the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere.

John Rolfe was among the Sea Venture survivors who now found himself in Virginia. After his first wife and daughter died in Bermuda, Rolfe completed the journey to Jamestown, introduced a sweet strain of tobacco from Trinidad to the colony, and married Pocahontas, daughter of Native American leader Powhatan. Bermuda Hundred, the first English administrative state in the colony, was named for the Atlantic archipelago that had saved the settlement. It was here, in modern day southeast Chesterfield County, that Rolfe cultivated the cash crop that sustained the fledgling colony.

Shakespeare’s storm

In William Strachey, a failed lawyer of precarious financial circumstances, the Sea Venture survivors found their scribe.

Strachey’s account of their ordeal, titled “True Repertory of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight,” proved to be a bestseller in England even though it was originally intended for Virginia Company shareholders.

As it had been roughly a year since the Sea Venture had been presumed lost, the survival of its passengers was big news in England. In November 1610, the Virginia Company published the promotional tract “True Declaration of the Estate of the Colonie in Virginia” that promoted their salvation in biblical terms. Church sermons celebrated “The Lost Flocke Triumphant” and rekindled faith in English colonization.

“The Sea Venture story would have been a huge event,” said Deborah Atwood, curator of the National Museum of Bermuda and a native of the archipelago. “It was effectively the flagship vessel. It had the governor, it had the admiral onboard, and it was, for all intents and purposes, lost at sea in an area known for shipwrecks.”

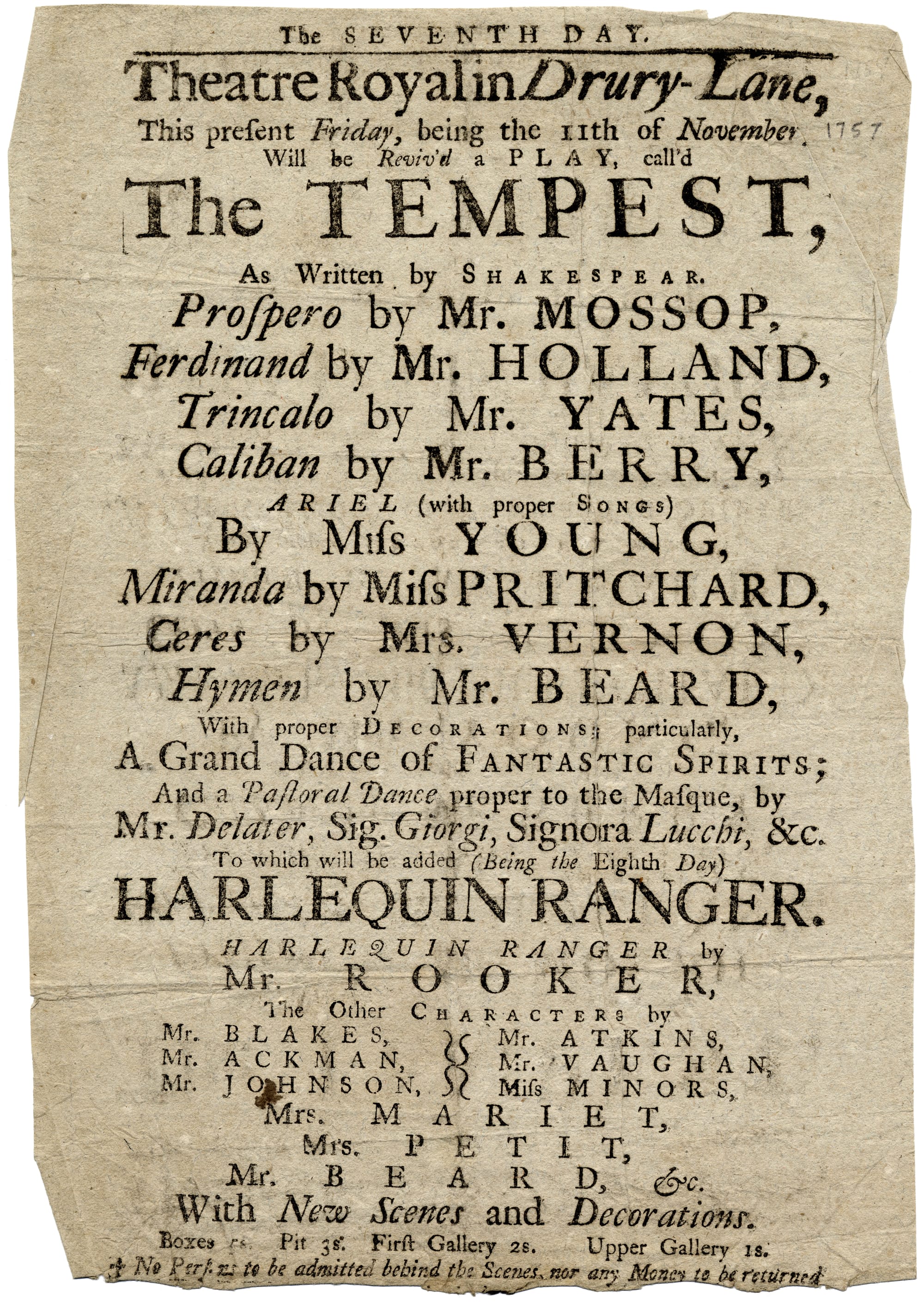

Many Shakespeare scholars contend that the Sea Venture and Strachey’s account of the wreck were the likely inspiration for “The Tempest,” the Bard of Avon’s tale of a powerful sorcerer who conjures a storm that destroys a ship and leaves its survivors shipwrecked on a remote island. The authoritative Arden Shakespeare states that “Shakespeare’s borrowings from several sixteenth-century travel narratives are overshadowed by his almost certain familiarity” with Strachey’s account.

“Strachey traveled in theatrical circles and was friends with friends of Shakespeare,” says Bly, noting that Strachey was friends with the Lord of Southampton, one of Shakespeare’s biggest patrons and a member of the Virginia Company’s governing council. “A lot of people have felt that Strachey’s account did get into the hands of Williams Shakespeare and probably inspired ‘The Tempest.’ Not verbatim, but there are instances and phrases in it.”

One such example is the appearance of St. Elmo’s fire, which appears in the text when Shakespeare describes Ariel as a fairy-like thing flitting about the mast of the ship. In another, Ariel mentions “the Still-vex’d Bermoothes,” a likely reference to the stormy reputation of Bermuda.

In the Fall 2008 issue of Shakespeare Quarterly, historian Alden T. Vaughan argued against claims that Strachey’s account didn’t influence the Stratford playwright: “The abundant thematic and verbal parallels between the play and ‘True Reportory’ have persuaded generations of readers that Shakespeare borrowed liberally from Strachey’s dramatic narrative in telling his island tale.”

At Jamestown, Bly says archeologists found a signet ring they believe belonged to Strachey, who, being a literary man, was made secretary of the colony. If the ring was Strachey’s, it’s possible that he used it to stamp the wax that sealed his account of the shipwreck.

Coming full circle, “The Tempest” was first performed at Whitehall Palace on Nov. 1, 1611, before King James I, the monarch for whom Jamestown was named.

The 'Bermudian connection'

With the cessation of BermudAir’s service, Virginia may have lost its direct link to Bermuda again, but the two former colonies are forever connected by their history.

Another link was formed in the summer of 1958 when a Virginian named Edmund Downing began a search for the wreck of the Sea Venture, the whereabouts of which were unknown.

Employed at the U.S. Naval Operating Base in Southampton, Downing began devoting his spare time to the search. Using a converted utility boat, Downing and another man began scouring the reefs off Bermuda’s St. George’s Island. On Oct. 18 of that year, the two discovered the remains of the wreck; identification of objects found at the site was conducted with the assistance of archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume and his wife Audrey at Colonial Williamsburg.

Today, the Sea Venture is heralded in Bermuda. The coat of arms and flag of Bermuda features a wrecked ship with a Latin motto meaning “Whither the Fates Carry [Us],” though sources vary on whether the distressed vessel is supposed to be the Sea Venture or another, earlier wreck.

“It’s a foundational wreck, in terms of British occupation of the island,” said Atwood of the Sea Venture, noting that some Bermudians can trace their ancestry back to the ship.

Without the Sea Venture, it’s possible that the English might have given up colonizing America altogether.

“The Sea Venture basically saved Jamestown,” Atwood said. “Everyone hears of Jamestown, but no one really understands that really important Bermudian connection.”