Photo essay: Richmond has a soil problem. Here’s what is being done about it.

A large percentage of Richmond's soils are comprised of a heavy clay, which is prone to compaction.

Compaction, which can happen from the pressure of heavy machinery or just footsteps trodding on soil, is a problem. This is because it condenses the porous spaces in soil that air, water, and nutrients occupy, which makes it difficult for the root systems of plants to establish themselves and limits the plants' lifespan and ability to thrive.

One way the city is increasing its climate resilience is by planting native plants and trees. Along with some of these plantings, the city’s soils are also receiving a novel process to combat compaction called ‘Soil Profile Rebuilding,’ which was created by Virginia Tech’s Urban Forest Ecosystems Lab under the direction of Dr. Susan Day.

“If the soil is compacted…then the roots can't penetrate that - those fine roots that take up water and nutrition…And they [trees] don't get taller, they don't recover really well from transplant shock, and ultimately they die and kind of live less.” — Lara Johnson, Virginia Department of Forestry Urban and Community Forestry Program Manager

There used to be three tennis courts at the corner of West 29th and Perry Streets in Fonticello Park on Richmond’s Southside. Now, where there was once a half-sized practice court there is a thriving, 6,000-square-foot piedmont grassland savannah, the sort of landscape that once covered large swaths of the southeast where bison and elk would graze.

The savannah restoration at Fonticello Park, which included the removal of the old tennis court, reprofiling of the soil, and subsequent new plantings of native trees and plants, was one of a handful of such projects made possible by grant funding obtained by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), "Greening Faith’s Places and Community Spaces," alongside funds contributed by Friends of Fonticello Park, and was brought to life by employees of the Department of Parks Recreation and Community Facilities and community volunteers.

“It’s just really ideal to identify a necessary impervious surface and make a complete 180 transformation. From something that was letting a lot of stormwater roll off it, to something that’s now lush with meadow plants with deep roots providing a bunch of habitat, pollinator forage, and stormwater infiltration.” -Kate Rivara, Community Engagement Manager, City of Richmond Department of Parks, Recreation & Community Facilities

CBF grant funding has covered costs necessary for the intensive process of removing impervious surfaces, the reprofiling of compacted soils, and purchasing native plants and trees. This work is a boon to Richmond's climate as impervious surfaces (think sidewalks, roadways, etc.) contribute to stormwater runoff into the sewer and ultimately the river, and the heat trapped in these surfaces is re-emitted back into the atmosphere, raising ambient temperatures (the urban heat island effect).

Some other projects made possible by grant funding in the past few years include lots of new trees: those planted after the removal of a basketball court at Branch’s Baptist Church and along Westover Hills Boulevard on the Southside, 70 new trees at Jefferson Hill Park in 2023, and 72 new trees around a vita course at Oakwood Playground in 2024. If you're interested in being a part of city tree plantings, check out those scheduled for this year's Richmond Tree Week.

Soil profile rebuilding and subsequent plantings have been carried out by the Department of Parks, Recreation and Community Facilities, alongside various community partners.

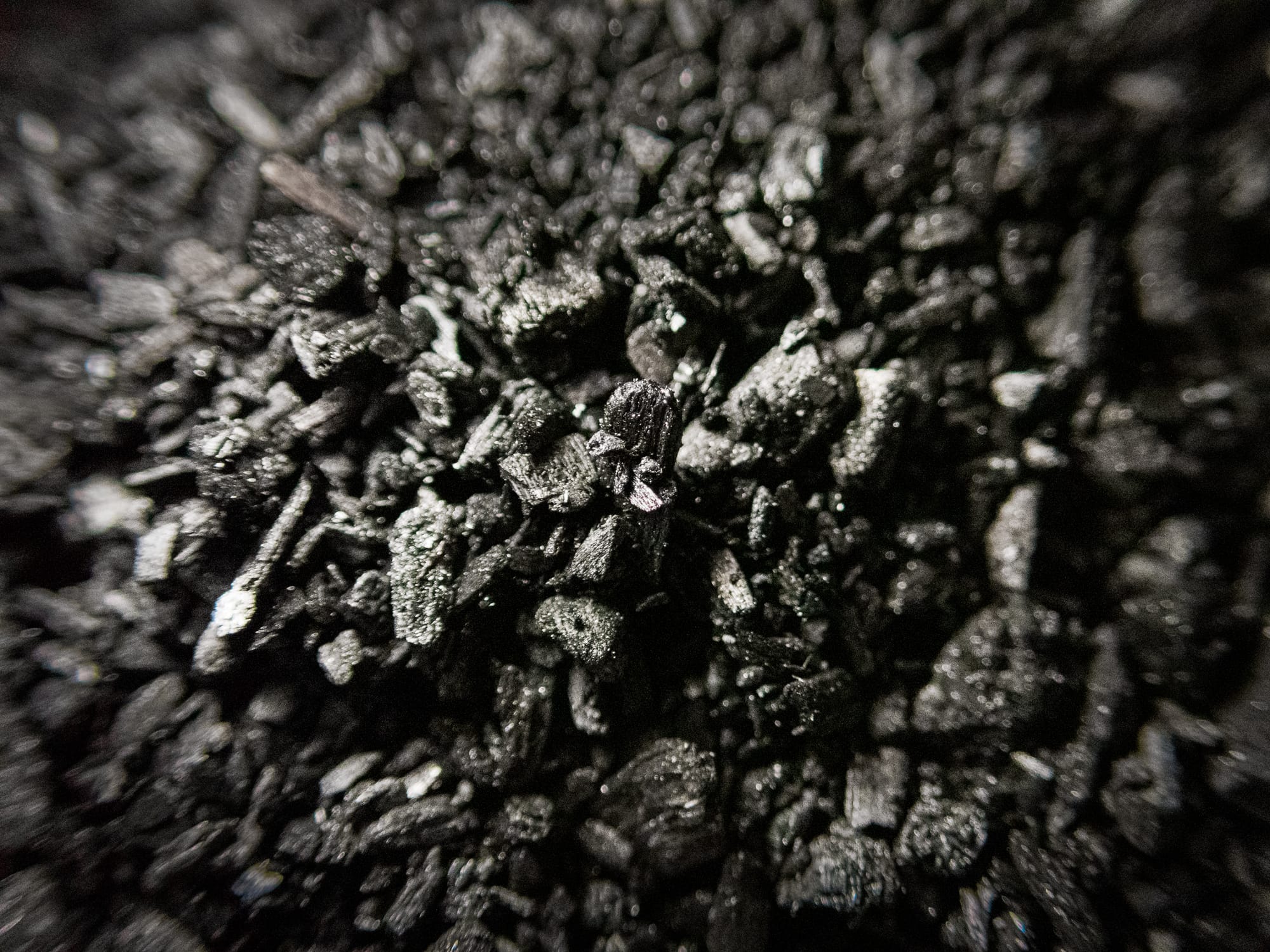

Coming back to Fonticello Park over a year and a half after the old court was removed, its soil amended, and new plantings made, tall grasses and colorful flowers such as plains coreopsis now reach taller than the average human, and are outlined by a rope-bordered walking path around which bees buzz and hover. The backbone of what makes all of this possible are two unique substances involved in soil profile rebuilding: biochar and compost.

Rebuilding the Soil

Soil profile rebuilding encourages plant growth by creating porous, uncompacted soils that provides space for nutrients, water infiltration, the exchange of gasses, and the proliferation of root systems.

Soil profile rebuilding is relatively simple: biochar and compost are mixed in at a specified depth with mechanically uncompacted soils. As a bonus, the process carries inherent ecological benefits, such as increasing soil’s ability to retain stormwater runoff, and the fact that biochar helps soil to resist further compaction. The compost provides an initial bolus of nutrients in the soil.

In many situations, using these substances also carries a combined price tag that is cheaper than buying conventional topsoil. This was the case with rehabbing the soil beneath the old tennis court in Fonticello Park.

According to Michael Gee, current PRCF Interim Superintendent for the Southern Divison who helped organize and oversee the project, the replanted space at Fonticello would have needed 138 cubic yards of topsoil, which would have cost around $5,400. Contrast that with the cost of amending the soil: $1,200 in compost and $500 in biochar.

This decrease in cost doesn’t incorporate another source of savings: if the city used new topsoil, it would have had to pay to haul away the old compacted soil.

”That's kind of the magic ingredient when you think about soil rebuilding… it [biochar] hangs on to that nutrition to help get those trees over, that like transplant shock, that initial phase of planting that is really challenging for trees to adapt to.” Lara Johnson, Virginia Department of Forestry Urban and Community Forestry Program Manager

Biochar is essentially fancy charcoal, its black grains full of microscopic pores that allow it to retain impressive quantities of water and nutrients. There is evidence of a substance similar to biochar, terra preta (meaning ‘black earth’ in Portuguese), having been used for soil amendment in the Amazon River Basin thousands of years ago.

Creating biochar utilizes a process called pyrolysis, where an input biomass (i.e., forestry waste) is heated to a high temperature in the absence of oxygen, either in industrial-sized or small-scale kilns, where the matter’s carbon is largely captured and locked into the biochar instead of being emitted as a greenhouse gas. Governor Glenn Youngkin has touted the benefits of producing biochar in Virginia via the ability to utilize state forestry waste (think of downed trees leftover after a hurricane or similar storm) to create the substance.

This is something the administration has supported via direct investment of funding and support from the Virginia Jobs Investment Program, which has helped two manufacturers of biochar establish themselves in the Commonwealth. The closest, Restoration Bioproducts, officially opened in September 2024 an hour to the south in Waverly, Virginia.

“I’ve planted roughly around 1,000 trees through grants and other small projects. I have started to use a combo of compost and biochar for every single planting, and certainly 3 years out we have around a 95% success rate for the trees we’re putting in the ground. That’s a pretty high survival rate in an urban environment: they’re dealing with pollution from cars, increased heat, bad stock or site selection.” — Michael Gee, Parks Recreation and Community Facilities Interim Superintendent, Southern Division

Composting's role

The other substance used for soil amendment in Richmond, compost, is made via a closely managed process allowing microorganisms to break down organic matter, which in its final form provides the nutrients for plants in soil profile rebuilding.

Compost used by the city for different projects is largely purchased. However, In the Whitcomb neighborhood on the Northside, the pungent smells that are a byproduct of manufacturing the substance are readily apparent as compost is produced each week in a city space home to the Richmond Community Compost Initiative, a program that has been in operation since 2022.

The program, carried out by the Department of Parks Recreation and Community Facilities, was created by Kate Rivara, Community Engagement Manager, City of Richmond Department of Parks, Recreation & Community Facilities and contractor Mark Davis, owner of Real Roots Food Systems LLC, and is based on programs at work in Philadelphia and other places worldwide.

The program runs on food scraps contributed by city residents, which in turn prevents them from being landfilled and mitigates a major source of methane emissions, which are over "...28 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere," according to the EPA. The program, which collects an average of 20,000 pounds of compostables each month, is recognized by its hallmark purple trash cans with green lids, and are present at locations such as community centers, community gardens, and public libraries.

On any given Tuesday (and sometimes on Wednesdays), you may see a solitary city pickup truck crisscrossing the city gathering the cans for delivery to the production site in Whitcomb. Much of the finished compost is given to community gardens, and other locations that host the cans. Some has even been used in new tree plantings. Coming this fall, the city-run program will be transitioning to a larger regional program facilitated by CVWMA.

Given that some city plantings have utilized city-made compost, a question arises: could the city also make its own biochar from sources such as city forestry waste? If so, the city could create both of the substances for soil profile rebuilding in the city from city-generated waste.

Tamara Jenkins, Richmond City’s Public Information Manager, said that although the city does not currently have a program to create its own biochar, it is a prospect worth exploring given how it is “...a sustainable approach that could align well with our long-term environmental goals.”

Max Posner is a documentary photographer based in Richmond, Virginia. You can view his work at maxposner.com.

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,200+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.