On Chamberlayne Ave., rezoning and rapid transit raise worries about displacement

A proposal to rezone a two-mile stretch of Chamberlayne Avenue where Richmond plans to run a new Pulse line is causing worries that increased development could lead to the loss of one of the city’s greatest concentrations of affordable housing.

“The fear we have is that our homes will be on the chopping block and will be knocked down,” said Emeka Anyawelchi, a member of New Virginia Majority and a tenant of Bloom Apartments, the largest of several complexes that sit on both sides of Chamberlayne. “This area is special to many of us who have no other option for affordable housing and also access to the bus.”

Nearly everyone agrees that the portion of Chamberlayne that runs from Brookland Park Boulevard in the south to Azalea Avenue in the north is unique.

Even as rents have risen precipitously citywide — one recent study found a typical Richmond one-bedroom apartment costs about $1,500 per month — the hundreds of units that line both sides of Chamberlayne have remained well below market value, offering a lifeline to people otherwise priced out of housing (even if they have, under various owners, offered substandard living conditions).

Unlike many concentrations of affordable units, the Chamberlayne housing is also fairly low density. None of the multifamily buildings rise above three stories, and most are set back from the road behind wide green lawns, interspersed with single-family homes and churches.

With plans for the north-south Pulse line and a major citywide rezoning underway, however, that could change.

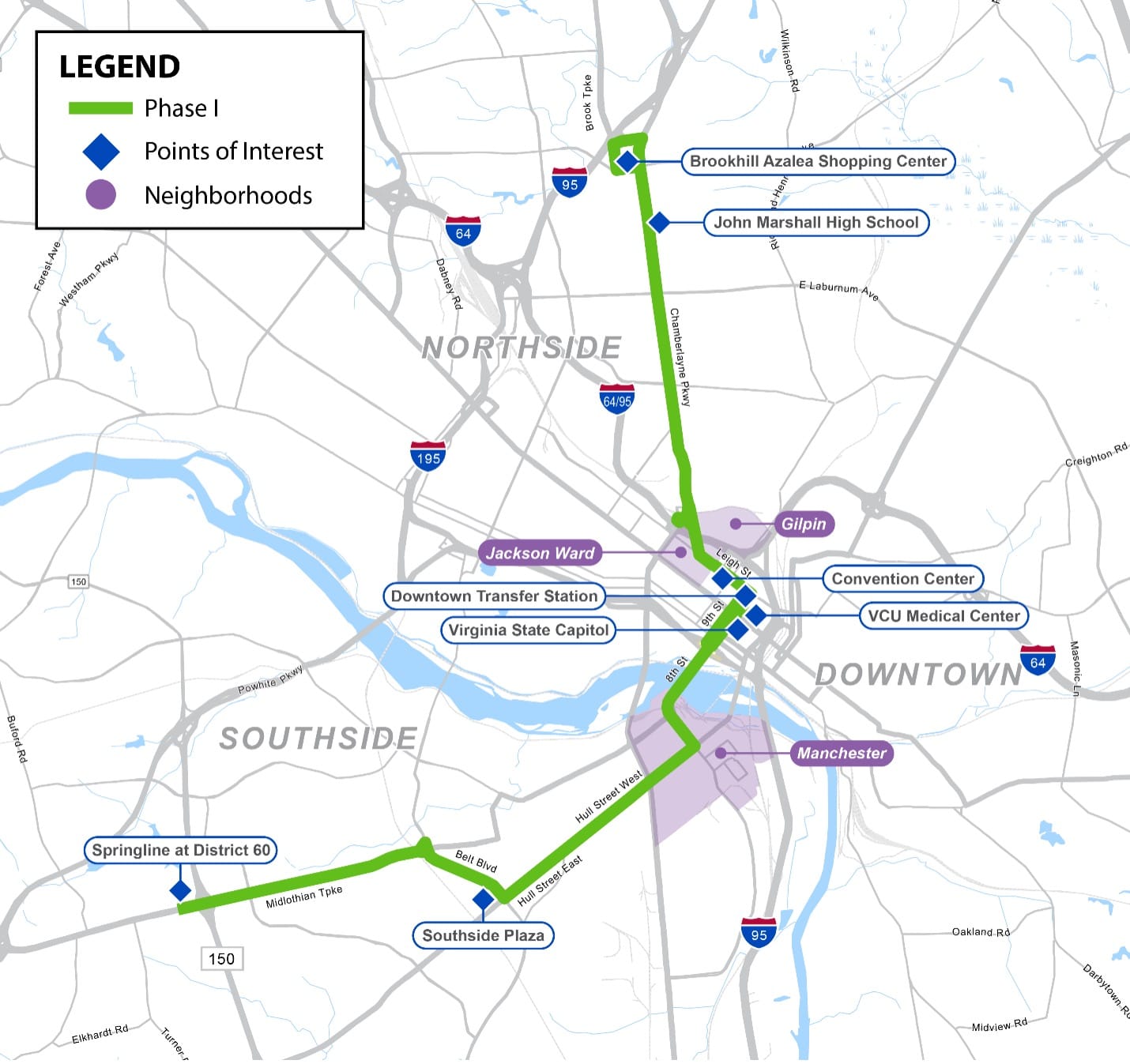

Like the original Pulse, the new bus rapid transit line will offer a more direct path through the center of the city, with more frequent and reliable service than the existing lines. Beginning at the Brookhill Azalea Shopping Center near the Richmond-Henrico boundary, it will travel down Chamberlayne before turning to cross the James River at the Manchester Bridge and then heading toward Hull Street and Midlothian Turnpike.

“Currently there is no direct service from the northern part of the city all the way down to the south. You have to take different routes just to get there,” said Frank Adarkwa, GRTC’s director of planning. “So look at it from an accessibility level, look at it from a connectivity level, it puts people in connection with a lot of jobs, social services, schools, all of that.”

As the corridor becomes a backbone of Richmond’s transit system, planners also envision development will follow. The first Pulse line along Broad Street is one model: There, large swathes around the bus rapid transit line in the Scott’s Addition area were rezoned to encourage denser, more mixed-use development.

GRTC is currently studying what’s known as “transit-oriented development” along Chamberlayne. But in the meantime, the corridor has become a point of particular interest in the wider overhaul the city is doing of its 1970s-era zoning code.

“This is a bit more of a planning issue than it is a zoning issue, so it's a little bit challenging for us to deal with,” consultant Rene Biberstein said Wednesday during a meeting of Richmond’s Zoning Advisory Council, a body that is helping guide the drafting of the new code but has no final decision-making power. “There was pushback from the public when we put this out there.”

Potential changes to neighborhood’s character debated

Today, the entire two-mile stretch of Chamberlayne is designated as multifamily residential, with requirements for wide front yards and heights capped at 35 feet, or roughly three stories. The new zoning — which is still in a draft stage and subject to change — would be a combination of multifamily zoning, with heights of up to four stories allowed, and mixed-use zoning, with heights up to six stories. Front yards for new development would also be much narrower, set back from the road by between 5 and 15 feet.

While any zoning change is likely to be felt gradually, with the new rules kicking in only when parcels are developed or redeveloped, many neighbors and residents worry that the combination of the north-south Pulse and the greater latitude for growth will not only transform the neighborhood’s character but cause affordable housing to disappear by making property values spike.

“If there are not protections added to Chamberlayne or any of the places the north-south BRT line is going through, there will be so much displacement,” said Rachel Hefner, an organizer with progressive group New Virginia Majority.

Hefner’s organization is not taking a stance against the Chamberlayne rezoning, she said. But it is pushing for planners to find ways to protect some of Richmond’s more vulnerable residents. She pointed to Charlottesville’s use of special overlays that aim to deter displacement by requiring developers to jump through extra hoops if they are eliminating affordable units as one possibility.

(Charlottesville’s zoning overhaul, like most others throughout Virginia, has been controversial; this summer, a legal challenge to the new code led to the city having no zoning whatsoever.)

Members of the Ginter Park community that flanks Chamberlayne have also worried that between the north-south Pulse and the rezoning, treasured green space like the tree-planted median that splits Chamberlayne’s four lanes in half will be lost.

“We are creating a heat island,” said resident Meg Lawrence.

Adarkwa with GRTC said the latest conceptual designs of the route call for the replanting of 400 trees along the new line’s path through Northside in response to neighbor concerns.

“We are very aware that the trees are going to be impacted,” he said. As of right now, GRTC expects to remove about 200. But, he continued, “for every tree that will be impacted, we are planting probably more than two.”

A ‘conflicted’ Council

Several members of the Zoning Advisory Council described themselves as conflicted when it came to reconciling the new bus corridor with neighbor concerns about green space and affordable housing.

“I tend to find myself persuaded that it’s a laudable policy goal to try to focus on transit-oriented development in key corridors such as this,” said Preston Lloyd, a ZAC member and lawyer who specializes in land use issues. “And yet I also hear very clearly the concern about what that density is going to mean in changing the character of those existing neighborhoods.”

Still, ZAC chair Elizabeth Greenfield, who also works for the Home Building Association of Richmond and serves on the Planning Commission, warned that even if planners back away from rezoning Chamberlayne, growth is likely to come due to the Pulse as developers seek to build using special use permits.

“As soon as that becomes final, you’re going to see development on this corridor. That’s what we saw with Broad Street,” she said. “I think we need to be forward thinking about what that street, that community, is going to look like, knowing that it's highly likely that [bus rapid transit] is coming.”

And Eric Mai, an affordable housing consultant with HDAdvisors, argued that requiring developers to go through the costly special use permit process would make it less likely for new projects to include affordable housing.

“By allowing for this kind of density by right, there are better opportunities for more affordable housing, more options,” he said. “So I support the direction that we were going.”

For now, the question of what the Chamberlayne proposal will look like remains open, with the ZAC delaying any decisions until they could consider the Pulse plan in more detail.

Still, council member and architect Dave Johannes struck an optimistic note.

“I'm definitely pro-[bus rapid transit] plan, but I also believe there's a way to create a BRT going down that street that still produces a nice boulevard,” he said. “And there's a way to develop this boulevard that does not separate the districts, but provides opportunities for people to have places away from their homes and services.”

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.