'It's part of who I am': Richmond's large Cambodian community is learning to embrace its heritage

Many Cambodian refugees felt the need to hide and assimilate when they arrived in Richmond more than 40 years ago. Fleeing a genocide that nearly destroyed their culture, they almost lost a part of themselves to survive.

Now, representing one of the largest Cambodian communities in Virginia, they and their children are showing pride in their dual Khmer-American identity.

Still weaving themselves into the fabric of America, many of the area’s Cambodian families are seeing their familial narratives mirrored in a new locally produced documentary.

“Chasing Cambodia” follows the story of a 39-year-old Richmond real estate agent and father of two who competed with the Cambodian national cycling team at the 2021 Southeast Asian Games. Directed and produced by two filmmaker friends that attended VCU with Phan, the documentary chronicles how his passion for cycling and reflections on becoming a dad inspired him to reconnect with his family’s roots.

Before visiting Cambodia with his wife for the first time in 2020, he started to think about what life would be like once his parents pass away.

“There was this ‘aha’ moment where I realized they’re my only connection to Cambodia,” Phan said in an interview with The Richmonder. “That’s why we decided to go to Cambodia as our last big trip before we have kids. … I wanted to soak it all up. I wanted to know where my parents came from.”

Phan says his journey healed invisible wounds from his youth.

“I think there was this guilt of pushing it away,” he said. “If I knew what I know now, I would have talked to my grandma so much more. I would have asked to hear more stories and cook a meal with her. There’s so much I wish I would have done.”

Others who grew up similarly – traumatized by the Khmer Rouge genocide and feelings of being unwelcome in their adoptive home country – see hope and joy in his story.

A hard journey

Many of Richmond’s Cambodian residents can trace their family’s arrival to the US to the 1980s and ’70s.

American jets bombed large swaths of Cambodia during the Vietnam War. Dictator Pol Pot took over afterward. His communist government seized private property and forced people into concentration camps. Ethnic minorities, college-educated citizens, religious people and suspected enemies were targeted. There were mass executions in the killing fields. Experts estimate that 1.5 million to 3 million people died in the genocide.

Many who escaped the terror have trouble talking about their experience.

“I can’t speak Khmer fluently. I understand it pretty well, so yeah, I caught my parents talking about it with their friends and aunts and uncles,” said Santana Hem, a 34-year-old chef aspiring to open a Cambodian-style restaurant in Richmond. “I knew about it early, like in kindergarten, but I didn’t really know the details until I was older.”

Survivors who escaped to refugee camps in neighboring countries eventually made it to America. In the Richmond area, a few churches sponsored families and helped them resettle.

The Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service reports that the Cambodian population in the US leaped from 18,000 in 1980 to 187,000 in 2000. About 2,000 of them live in the Richmond area.

“Henrico has the second largest Cambodian population in Virginia after Fairfax County, but Cambodians make up a larger share of both Henrico and the Richmond Metro Area's population than in Fairfax or the Washington DC Metro Area,” said Hamilton Lombard, a demographics research manager at the University of Virginia center.

People who came as children or young adults still have memories of tip-toeing around landmines, hiding in humid jungles and scavenging on mice and insects to survive.

Meng Ky, an owner of a local family-run medical practice, said he was taken from his parents when kids typically learn to read and write. He ran away from a labor camp and stayed hidden near another camp where his mom was taken.

“I think back on it all the time. I didn’t have a place to sleep. I didn’t know where my family was,” he said. “Imagine in one life you see all that. Then all of a sudden you’re here in the United States, you have your own office, a good job, a nice car – I mean, sometimes I pinch myself and wonder, ‘Man, is this real?’”

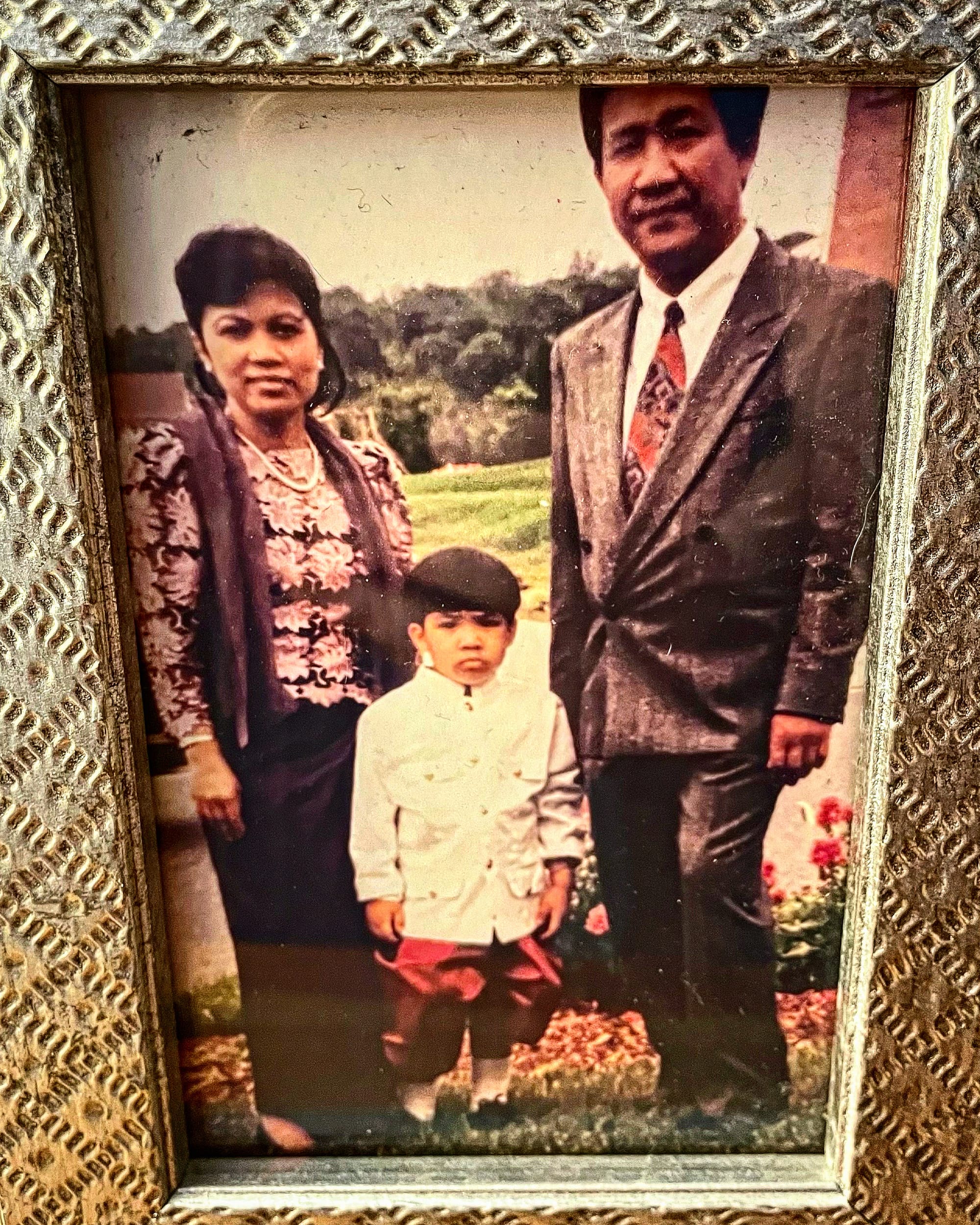

He eventually reunited with his family and came to the US when he was 11. Pim Bhut arrived in 1984 when she was 27 years old. She said a man saved her as they were running away in the jungle. They made it to a Thai refugee camp and fell in love. They had a son in the camp, before coming to America.

There were stories of hope and perseverance. But it was undoubtedly painful.

“I think that’s why the older generations don’t like to talk about it. They’re either traumatized or just don’t want to bring it up, so they put it behind them,” she says. “But I tell my story all the time.”

Bhut couldn’t speak English when she arrived in Richmond. But she got a job at a sandwich shop near the federal courthouse downtown.

Within a few months, she started talking more confidently as she became friendly with the judges, lawyers and news reporters whose orders she remembered by a system of numbers for the cold cuts. A few patrons encouraged her to dream big now that she was living in the US. She started her own housekeeping company.

As her American-born daughter started grade school, however, she struggled with feeling inadequate.

“We never went to PTA meetings or anything to do with the school until she was in high school. She was just embarrassed that her Asian parents don’t know anything, don’t speak English and are poor,” she said. “It made me sad that she would say that. But it’s not like that anymore.”

Bhut said her children have more pride in their culture today. (Her daughter, Tida Tep, helped design Chasing Cambodia’s title, which includes a translation of the movie’s name in a traditional Khmer script.)

Shaping an identity in a new country

Bhut wanted nothing more than a comfortable life for her children.

She told them education was most important, but like many other Cambodian-Americans, she also hoped that she would be proud of where they came from. Growing up somewhere else, though, it takes effort to not lose touch with the cultural heritage that shapes a person’s life and identity.

Discovered in the lifeless arms of her mother, Aiyana Bradshaw came to the US as an infant in 1975. She was adopted by a mixed-race family in San Francisco.

Due to complications in bringing her over, Aiyana was listed as a Vietnamese citizen. “I had a hard time self identifying. Am I white? Am I Black? Am I Cambodian? Am I Vietnamese? And I also had a little sister at the time who was Chinese,” she said. “People used to make fun of me because I had white parents, so I got into a lot of arguments.”

Her adoptive mother, however, always told her where she was really born. With her mother’s support, Bradshaw learned where she came from spending time with other Cambodian people.

Decades later with two adult daughters, Bradshaw still attends ceremonies and festivals at Cambodian Buddhist temples like Khmer Samacky in Henrico to feel at home. She said it’s one of the best ways to keep her family connected to the Khmer language and folklore.

“They love their culture. They are half-Black, half-Cambodian. But they're very into the Cambodian culture,” she said.

With a granddaughter that’s two years old, Bradshaw hopes that she’ll always have memories of dressing in the traditional silk dresses of her grandmother’s people.

“I’ve brought her to the temple a few times. She got blessed here when she was first born. She also knows certain words ... in Cambodian. And she wears Cambodian clothing,” she said. “I want her to learn how to dance, too.”

'Pushing away of that culture'

Located in Richmond National Battlefield Park, the Khmer Samacky temple features a rug-filled prayer hall, golden statues of Siddartha, lodging for monks and amenities for large events. There’s an outdoor stage, picnic shelters and tables. Many have contributed time and money to sanctify the monastery and preserve their heritage.

Though his parents converted to Christianity, Phan said gatherings at Buddhist temples and other family functions kept him connected to his culture when he was little.

“Having my grandmother around … she was kind of the glue that kept the family together. So it was always around me,” he said. “It was always something that was celebrated.”

Trying to fit in with other kids in Henrico County in the early 2000s, though, Phan did not talk much about his family’s colorful background or how his parents were refugees. He started to hide those things by the time he got to Godwin High School.

“I went to an all-white high school, basically,” Phan said. “I didn’t want to stick out. I didn’t want to be the different kid. There was like an active pushing away of that culture.”

Vannara Om, a member of the Khmer Samacky temple who also grew up in Henrico, said he remembers a similar tension when he was a student around the same time at J.R. Tucker High School.

“We pretty much had the same lineage of friends,” Om said. “After watching his film, it felt like it was definitely a reflection of my life.”

Om played sports and made friends with kids from other backgrounds. It was a transgression to some. Often at temple events and Khmer parties, other kids gave him a hard time for trying to be too much like his American friends.

“My parents were a big catalyst for staying in touch with the community and volunteering,” Om said. “I never felt ashamed. I felt like I didn't know which side to go. So I just stayed in my lane, in the middle.”

Phan said his decision to largely ignore his Cambodian heritage extended into college.

Aspects of his American upbringing in Richmond influenced his behavior. Skateboarding preoccupied his high school days. His interests shifted to Sailor Jerry tattoos and fixed-gear bikes at VCU.

What initially started a method for getting around campus and exploring the city with his friends became a passion. Then he learned about the annual bike competition series in Bryan Park.

“That was my first race. I got my teeth kicked in,” he said. “I kept showing up.”

His high-energy aura matches RVA’s.

“It’s still part of who I am,” Phan said. “I feel like it’s built into my DNA. That’s why I love the aggression and speed of bike racing.”

Phan’s thrill-seeking nature, fostered by Richmond’s bicycle scene, eventually reconnected him to the missing part of himself. When he visited Cambodia for the first time, he quickly found native cyclists. His athleticism and experience made him a strong candidate for the country’s nascent cycling team.

He trained for months in preparation for the race, dedicating himself to compete. “I didn’t win,” he said, “but I was there.”

Reconnecting through tradition

Sports and arts have helped other first-generation immigrants form stronger ties to their culture.

Santana Hem, the local chef, said he originally had a career in finance before entering the culinary world working in high-profile kitchens in New York City. His parents weren’t thrilled about it, but Hem said the love he felt through his mom’s home cooking inspired his passion.

“We never went out to eat,” he said “That was probably mostly because she didn’t want to spend money to eat out, but she also thought her food was better than everyone else’s.”

Hem said he’s still figuring out plans to open a Cambodian restaurant. Right now his efforts are focused mostly on pop-up events and home-delivery orders for black sesame chocolate chip cookies.

He says his family has warmed to the idea as he’s sought to embrace his heritage.

“We're growing and there's more Cambodian restaurants opening up and things like that, but I just wanted to honor my upbringing,” he said. “Everyone's doing Italian and French and things like that, so I wanted to do something new and honor my mom.”

Over the past year, Meng Ky has been supporting his son’s burgeoning career as a professional fighter in Cambodia. His son, Ethan, is training in Kun Khmer, a Cambodian martial arts tradition similar to kickboxing.

Ethan, 23, navigates being both American and Khmer living in Cambodia. He’s been billed as an American, but he also wore a Cambodian flag entering the ring in his pro debut. Meng said he’s immensely proud to see how his kids and others like them are embracing both parts of their identity.

“Back in our day, we just wanted to be American,” he said. “I wouldn’t even want to speak Khmer. … That’s why I’m so proud of this generation.”

Instead of hiding, he sees families like his own flying Cambodian flags and stickers on their cars and homes. He says it’s especially gratifying to still hear their native tongue.

“Before my son’s first fight, they interviewed him and he spoke Khmer,” he said. “It gave me chills.”

Aside from cooking, Hem said he mostly stays in touch with his Cambodian side through his parents. Earlier this year, he built his mom a new greenhouse at her home in Fairfax so that she can grow even more lemongrass, peppers, eggplants and herbs for her traditional home cooking.

Of all the things in her garden, a Makrut lime tree she’s nurtured since coming to America is perhaps the most symbolic of his relationship to his heritage.

“She makes me lug it inside every winter. It’s spiky … and like 120 pounds or something,” he said. “It’s older than me. It’s been propagated so there’s little baby trees, too.”

He says it’s something he plans to inherit when she passes away. Even if it’s cumbersome and hard to maintain, it’s something he cherishes.

He can’t imagine letting it wither and die. It means too much to him.

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.