Is this Fan monument an ode to heroic efforts or an act of 'fictional self-glory'?

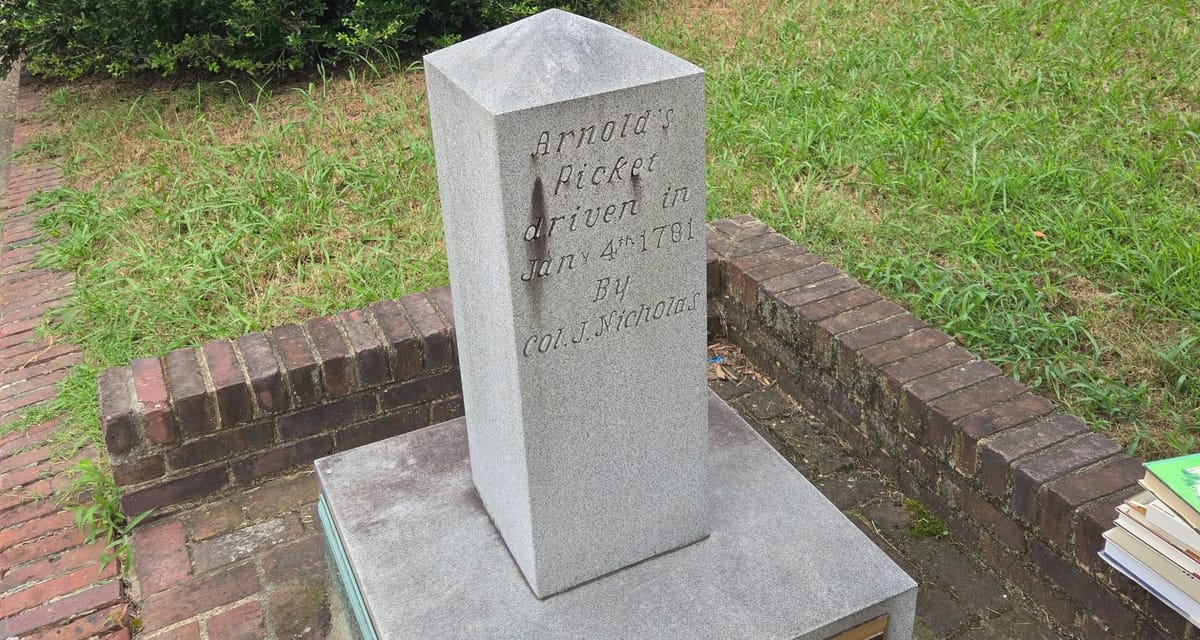

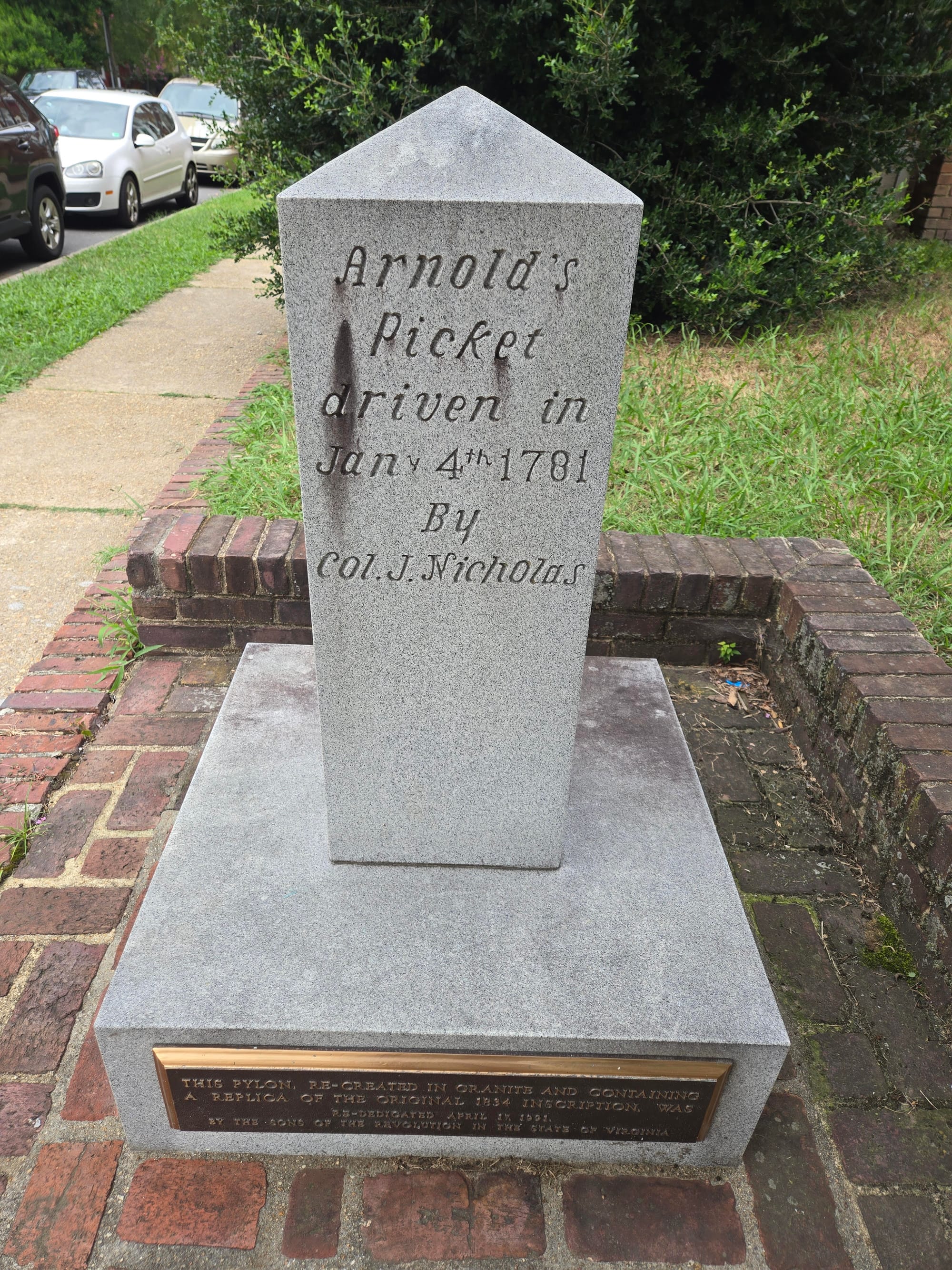

A granite obelisk located at the corner of Grove and Mulberry in the Fan District stands out among Richmond’s many historical monuments not because of its size (it’s just three feet tall), but because it may be based on a tall tale.

The story of “Arnold’s Picket” took place during the 1781 British invasion of Richmond during the Revolutionary War.

Here’s what we know for sure happened on January 5, 1781: As 1,600 British troops approached from the east, Richmond was defended by several hundred militiamen hastily assembled on high ground on what is now Chimborazo Park. Many lacked firearms. When a portion of the much larger British forces marched up the hill, the militia broke and ran for the woods. They may or may not have gotten off a single volley.

Governor Thomas Jefferson’s name was besmirched for not calling out the militia sooner, leaving him no choice but to abandon Richmond, a small town that only the year before had become the capital of the rebelling Virginia colonists.

To add insult to injury, the hit-and-run mission against Richmond was led by the traitor Benedict Arnold. Arnold’s troops plundered a nearby foundry, destroyed government records and set several buildings on fire. Within 24 hours, Arnold marched out of town without losing a single man.

Eight months later, the British forces surrendered to Americans and French troops at Yorktown. But the sacking of Richmond was a humiliation that Virginians would soon rather forget.

In 1819 – nearly 40 years later – the militia officer who was in charge during that dark day in Richmond history stepped forward with a heroic story that, after subsequent telling, credited him with Arnold’s “repulsion” from Richmond.

Did it really happen?

John Nicholas Jr. was an aging Revolutionary War veteran who believed he had been shortchanged in compensation for his military service. In seeking a fatter state pension, Nicholas had every reason to embellish his war record.

In his book “Discovering Richmond’s Monuments,” Robert C. Layton said that some are convinced the monument is an “act of fictional self-glory.”

Christina Vida, a curator with the Valentine Museum, believes that Nicholas “gussied up” events, but stopped short of calling the monument “fake history.”

“We are appreciative of the marker because it gives us a chance to tell what happened in 1781,” Vida said, “even if it doesn’t tell the whole story.”

Vida noted the available historical record lends a whiff of plausibility to the general outline of Nicholas’ story. Jefferson placed Nicholas in command of the militia at Richmond with orders to stay close to the enemy, but not engage them directly. There are contemporary references to Arnold posting pickets (small groups of soldiers who can warn of an attack) on the outskirts of town.

It is possible that Nicholas and his men encountered a picket in a place called Scuffle Town (which later became the Fan). It’s also possible a skirmish ensued, which caused a few British soldiers to fall back toward Richmond.

In Nicholas’ telling, the encounter at Scuffle Town spooked the British and prompted Arnold to evacuate Richmond with “great precipitancy & confusion.” In other words, Nicholas and his men sent Arnold packing back down the James River to his winter headquarters in Portsmouth.

There is nothing in the historical record to suggest that Arnold faced resistance that chased him from town. His orders were to smash and run, not to occupy. All other accounts indicate that Arnold left town at a time of his choice.

Nonetheless, the General Assembly rewarded Nicholas with additional compensation for his service. But that didn’t satisfy him. In 1835, shortly before his death, Nicholas himself placed a stone marker – the precursor to the current granite obelisk – that would ensure his name would not be lost to history.

Finding fame and making enemies

John Nicholas Jr. was born in 1758 or 1759 into a family of privilege near Charlottesville in what later would become Buckingham County. His father was clerk of the Albemarle court and owned Seven Islands Plantation near where the Rockfish Creek empties into the James River.

At age 17, Nicholas interrupted his education to accept a captain’s commission in the local company of “minute men.” In 1777-78, he served in the 1st Virginia State Regiment under General George Washington. Nicholas completed his military service as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia state militia, which is what placed him in Richmond during the fateful events of January 5-6, 1781.

After the war, Nicholas returned home where he eventually succeeded his father as clerk of Albemarle Court. He gained notoriety by making a habit of stirring up political controversies. One historian called him a “meddler and marplot with a genius for intrigue.”

An ardent Federalist, Nicholas was author of a series of letters published under the name Decius that leveled personal invective against leading Virginia anti-Federalists, particularly former Governor Patrick Henry.

In 1797, Nicholas sought to ingratiate himself with then former president George Washington by accusing Jefferson of attempting to entrap Washington with a forged letter. The so-called Langhorne letter incident led to an irreconcilable break between the two founding fathers, prompting Jefferson to label Nicholas “a malignant neighbor.”

After Jefferson became president in 1801, Nicholas is believed to be the source of a Federalist preacher in Connecticut whose sermons described Jefferson as a “whoremaster” who kept at Monticello a mistress named Sally Hemings.

Nicholas relished his impact on political events. He once boasted that the Decius letters “excited an interest and anxiety in the public, beyond anything that was ever witnessed before and since, from any publication in this country.”

By 1819, Nicholas decided to cease all political feuds. He had come to believe that Virginia had not adequately compensated him for his services during the Revolutionary War. Golladay said Virginia granted Nicholas 4,000 acres of land, but he considered that inadequate because the land was valued at 40 cents an acre.

Nicholas understood that success would require the goodwill of prominent Virginians like Jefferson. In fact, Jefferson wrote a letter on his behalf of his former nemesis, but could not recount any specific details of Nicholas’ actions during the 1781 invasion of Richmond. (In his letter, Jefferson got the date wrong. He had Arnold arriving a day earlier, on January 4. This may explain why the Arnold’s Picket monument places the events one day before they could have happened.)

The additional compensation did not satisfy his desire for recognition. In 1835 – 15 months before his death — Nicholas took steps to ensure his place in Virginia military history. He organized a ceremony to place a stone marker at the approximate spot in Scuffle Town where he said he had encountered Arnold’s picket. An inscription read: “Arnold’s Picket driven in Jan 4th 1781 By Col. J. Nicholas.”

He placed an ad in the Richmond Enquirer that perpetuated his story, tying his actions to Arnold’s “consequent expulsion from Richmond.”

As streets in the Fan neighborhood were laid out in the early 20th century, the stone marker ended up in the backyard of a home at the corner of Grove Avenue and Mulberry Street. The owner of the house moved it to the front yard, at the edge of the street.

In 1924, the Sons of the Revolution affixed a brass marker. In 1948, the group replaced the deteriorating stone with a granite obelisk. It added a second plaque, which notes this is approximate spot “where Benedict Arnold’s attack during the Revolution was repulsed.”

The wording could leave a reasonable person with the impression that Arnold’s invasion of Richmond was unsuccessful.

In 1990, the stone disappeared, but was later found. The Sons of the Revolution rededicated the marker in 1991.

When asked if the Sons of the Revolution had documented the story behind the monument, Carter Reid, past president of the group’s Virginia Society, emailed, “Unfortunately, we are more of a lineage society than a historical society.”

When asked if the group had concerns about lending its name to an event that may not have happened, Reid wrote, “To say that the event didn't happen is quite the stretch don't you think?”

One historian has written that Nicholas fabricated another Revolutionary War story in an attempt to wrest more compensation from the General Assembly.

In 1833, two years before he placed a stone marking the supposed spot of Arnold’s Picket, Nicholas sought to win claims based on the war record of a first cousin who shared the same name and who had died in 1818.

“Nicholas was apparently hoping that the intervening years had so confused the records that he could get away with the deception,” historian V. Dennis Gollady wrote in a 1978 article in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. “Fortunately, justice was served when the General Assembly rejected this last claim in 1835.”

Resources used to compile this story:

Cecere, Michael, “The Invasion of Virginia 1781,” Westholme Publishing, 2017.

Dauer, Manning Jr. “The Two John Nicholases: Their Relationship to Jefferson and Washington,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Jan., 1940).

Dawson, Henry B., “Battles of the United States, Volume I, New York, 1858.

Golladay, V. Dennis, “Jefferson's "Malignant Neighbor," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, July 1978.

Holton, Woody, “Liberty is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution,” Simon & Schuster, 2021.

James, John Q, “Arnold’s Picket Line,” Sons of the Revolution in State of Virginia Magazine, July 1924.

Jefferson, Thomas, Letter to John Nicholas Jr, November 10, 1819.

Layton, Robert C., “Discovering Richmond’s Monuments,” The History Press, 2013.

Nicholas, John Jr, “John Nicholas’s Memorial to the Virginia General Assembly,” 1781.

Nicholas, John Jr, Letter to Thomas Jefferson, received November 9, 1819.

Nicholas, John Jr, Newspaper ad, Richmond Enquirer, December 31, 1833.

Ward, Harry M., “Richmond during the Revolution, 1775-83,” University of Virginia Press, 1977.

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.