In Richmond, what is ‘affordable’ housing?

Just under 50 years ago, a real estate agent placed an advertisement in the paper for a three-bedroom, one-and-a-half story house in Bellevue with a basement and a fireplace. The price was $31,950.

Today, adjusted for inflation, the price of the house would be around $186,600. City property records show it still has three bedrooms and one and a half stories that together make up a modest 1,400 square feet. There is only one bathroom.

The actual value according to Richmond’s latest property assessment? $344,000. And even that is lower than the city’s median sales price of a single family home this year, which as of November was over $428,000.

As home prices have soared since the pandemic and newcomers have continued to stream into town, housing affordability has become one of Richmond’s most pressing issues. The City Council declared a housing crisis in 2023, and Mayor Danny Avula, a Church Hill resident, has repeatedly said home affordability concerns were a primary motivator for his campaign.

The challenges Richmond is grappling with aren’t unique, although it has been particularly hard-hit by the influx of higher earners from more expensive cities like Washington, D.C. Nor are the pressures likely to disappear anytime soon: Last week, Realtor.com ranked Richmond 6th on its list of 2026’s top markets.

“This is really happening in communities all across the US in response to really unprecedented challenges around affordability,” Gabe Kravitz of the Pew Charitable Trusts said during a recent panel discussion held by the city. “Rents are at their highest levels. It's becoming hard to access homeownership. Displacement is surging in places that are not building enough housing, and homelessness is reaching record levels.”

Richmond officials are trying an array of tools to keep housing costs down, although attempts by some City Council members to lower real estate taxes have failed. Affordable housing performance grants, the Affordable Housing Trust Fund, low-income home repair programs and the RVA Stay initiative have all either incentivized the production of affordable housing or offered assistance to people struggling with high rents or other housing costs.

Most controversial has been Richmond’s overhaul of its 50-year-old zoning code, which among other goals aims to encourage the development of affordable housing by allowing increased density citywide.

“The code refresh is a tool that we can use to allow for more housing to be built,” Avula told 8th District residents last week. “The second way that we need to address this is by investing more dollars in affordable housing, because the only way you get to housing affordability is by investing public dollars to bring down the cost of building.”

But as Richmond has increasingly invested money in affordable housing and planners have greenlit denser infill projects, residents have more frequently asked: What does the city mean when it talks about affordable housing?

Affordability and area median income

At first glance, defining affordability seems like a straightforward task.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines affordable housing as housing that costs no more than 30% of a household’s gross income, including utility payments. Households that devote greater percentages of their income toward that bucket are described as “cost-burdened.”

While local governments are free to set broader definitions of affordability, many rely on the HUD definition for ease and to make it simpler to draw comparisons with other areas.

To put numbers to that definition, every year the federal government calculates what’s called the “area median income” for each region across the U.S.

The AMI is then used to determine eligibility for various housing subsidies, including the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program — the biggest producer of affordable rentals in the U.S. — and HOME grants.

AMI is also used to evaluate whether a family is eligible for housing produced using those subsidies and to calculate allowable monthly rents based on the idea that no one should be spending more than 30% of their income on housing.

However, HUD doesn’t assign an AMI to every single city or county. Instead, it calculates AMIs for broader geographic areas that then apply to all of the jurisdictions within that area.

Richmond is part of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area, a grouping of 17 localities that also includes the cities of Colonial Heights, Hopewell and Petersburg and the counties of Chesterfield, Hanover, Henrico, Amelia, Caroline, Charles City, Dinwiddie, Goochland, King William, New Kent, Powhatan, Prince George and Sussex.

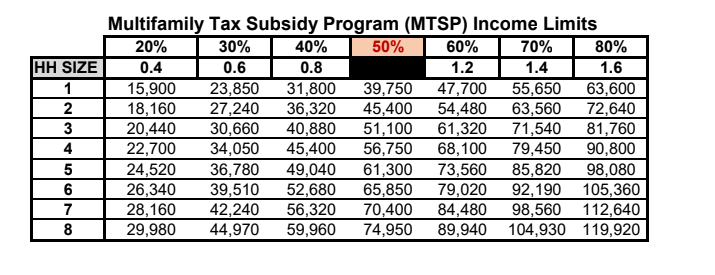

For 2025-26, HUD set the area median income for the Richmond area at $113,500, meaning that households making less than that amount could be eligible for affordable housing programs or housing developed using subsidies.

For the Richmond metro area, a household making 80% of the area median income could range from $63,600 for one person to $72,640 for two people, $90,800 for four and $119,920 for eight.

Lower down the scale, incomes for 30% AMI run from $23,850 for one person to $27,240 for two, $34,050 for four and $44,970 for eight.

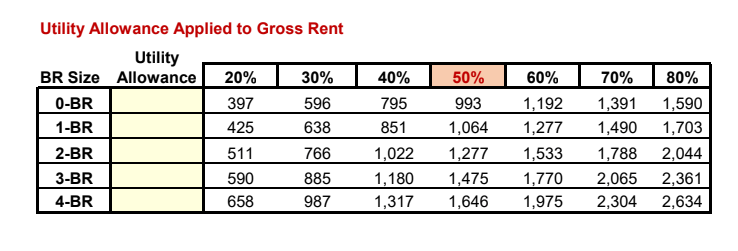

Meanwhile, rental costs for a person making 80% AMI could be up to $1,703 for a one-bedroom unit or $2,044 for a two bedroom. Someone making 50% AMI could pay up to $1,064 or $1,277 for those units, while someone making 30% AMI would pay no more than $638 or $766.

Those numbers often raise eyebrows in Richmond city, where the 2024 median household income of $63,390 falls far below the federal AMI calculation for the area. While debates about AMI tend to be complicated and technical, some elected officials have long complained that wealthier, more populous counties within the Richmond metro area skew the AMI and put low-income city residents at a disadvantage.

Who qualifies?

Many affordable housing developers say it’s not unusual for people to conflate “affordable housing” with “public housing.” But while both rely on public funding — nearly all affordable housing in 2025 uses subsidies in some way, shape or form — affordable housing covers a much broader range of incomes.

At 60% AMI, “we’re talking about people who have full-time jobs, who probably work at [Richmond Public Schools] or wherever,” said Charles Hall, vice president of housing for Commonwealth Catholic Charities. “This is almost like workforce housing that we’re talking about, middle-income housing.”

Even that pool is expanding, said Marion Cake, vice president of affordable housing development at project:HOMES, one of the most active builders of affordable homes for sale in the Richmond metro region.

While families making 80% to 120% AMI used to be served by the market, with no need for any type of subsidy to be involved in homebuilding or the home purchasing process, “that’s not really true anymore,” he said.

It’s a point Cake has made repeatedly in housing discussions, where he warns policymakers that nonprofit developers can’t meet the growing demand for affordable homes alone.

“Many buyers with incomes between 80 and 120% of the area median income — so that’s a single person making between $60,000 and $90,000 a year — there’s nothing that they can afford to buy,” he said during an April zoning panel held by the city. “The developers are not able to produce something feasibly that will meet their budget.”

Research earlier this year by the Partnership for Housing Affordability, a regional nonprofit that focuses on housing policy, found that the income needed to buy a single family home in the Richmond region, based on the then-median price of $410,000, had nearly doubled in four years, from $62,005 in 2020 to $122,866 in 2024.

The steep increase in prices has particularly narrowed the pool of starter homes available for younger people, a trend seen nationwide. While the median age of first-time homebuyers was 29 in 1981, this year it was 40, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Those changes have also triggered complicated feelings among many Richmond residents who live in neighborhoods that they are accustomed to thinking of as affordable but are now out of reach to many thanks to soaring home valuations.

The Union Hill area around the Jefferson Avenue corridor “until a few years ago was very much drug-inhabited, very much drug-overrun,” one man reminded the city’s zoning advisory council recently. West Grace Street residents on the edge of the Fan have repeatedly commented on the street’s gritty past and the drug and prostitution issues many had to navigate when they first moved into their homes here.

But today, most of the homes along West Grace west of VCU are valued at anywhere from $500,000 to more than $1 million. Current listings on Union Hill hover around $400,000.

“First-time homebuyers can’t compete in Richmond’s housing market anymore,” resident Tyler Misencik told the zoning council this September. “There aren’t enough affordable entry-level homes, and it’s turning many people who live in Richmond to the surrounding counties in search of more abundant and less expensive housing.”

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org