In a supposedly tight budget year for Richmond government, pay bumps for senior officials spark fierce debate

In 2022, there were five jobs in Richmond city government that paid median salaries of over $200,000 per year.

As of early 2025 that number had jumped to 45 positions, according to pay band data officials recently presented to the City Council.

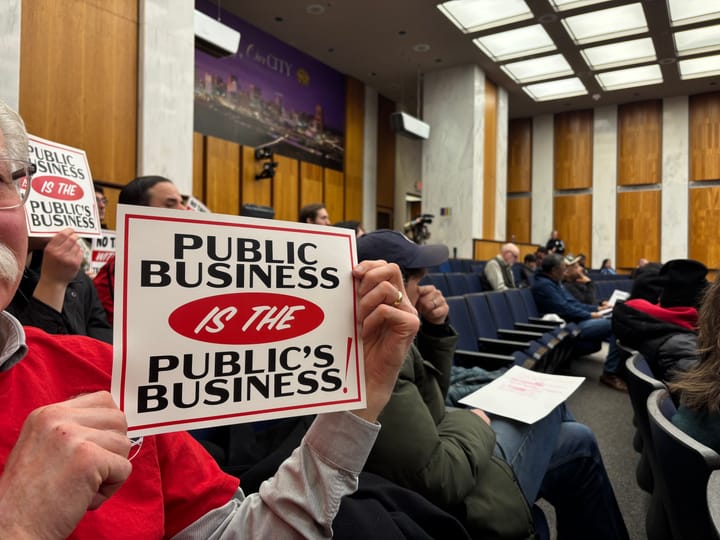

That growth — which came as city leaders were making a concerted effort to attract and retain high-level talent and shift to a unionized workforce through collective bargaining — has drawn pushback from some newly elected members of City Council.

Runaway salaries at the top levels of City Hall, Councilors Kenya Gibson (3rd District) and Sarah Abubaker (4th District) have argued at multiple budget meetings, should be one of the first places where officials can afford to slow down spending. Especially at a time when residents are being told there’s not enough money to go around even though the pending city budget envisions higher tax and utility bills for the fiscal year that starts July 1.

Instead of approving an across-the-board salary increase of 3.25% as proposed by Mayor Danny Avula, Gibson and Abubaker proposed saving nearly $750,000 by not granting raises to non-union employees making over $150,000.

The pay question has sparked a fiery debate over how Richmond should live up to the progressive values many of its leaders espouse as policymakers try to improve the culture and performance of City Hall.

Should fairness dictate that everyone gets a raise no matter how much they make and how much their salary has already grown? Or should higher spending on staff mostly benefit frontline workers making well below six figures?

“We’re using equity as a PR word. When in reality we are making sure that the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting moderately less poor just so that they stay quiet,” Abubaker said at a budget meeting Monday. “This is not corporate America. This is taxpayer dollars. And people are tired of this.”

The suggestion to block raises for high earners has drawn the ire of City Hall’s old guard, prompting several department directors to take the unusual step of publicly opposing the proposal as needlessly divisive and bad for morale. Several of the council’s more experienced members have pledged to support the city’s staff by giving raises to everyone.

“Let’s not sit here and try to say that our employees are here just to get some money,” said Councilor Reva Trammell (8th District). “They work. And they deserve every penny of it.”

Council President Cynthia Newbille (7th District) said the $20 minimum wage the city adopted for its employees allows workers at the lower end of the pay scale to “more than just survive but thrive.” But not giving raises to those at the top, she said, would leave a group of employees “unattended.”

“They’re certainly non-union but they certainly are our staff,” Newbille said.

Department heads speak up

Across two budget meetings Monday, nine senior City Hall officials spoke against the proposal for more targeted raises.

“Inflation doesn’t skip over senior-level positions,” said Charles Todd, the city’s director of information technology.

Several officials warned the $150,000 cutoff could create salary compression, leading to situations where a subordinate earns as much or more than their boss.

Director of General Services Gail Johnson said some employees getting raises while others go without would set back the team-building efforts she’s started as the head of a newly formed department.

“To not give raises across the board kind of negates my push that we’re all in this together,” she said. “It creates separation and it creates a sense of not being appreciated.”

Attempting to cut positions or withhold raises, said Director of Emergency Communications Stephen Willoughby, could set the city back “years.”

“Employees will leave,” he said. “And they have in the past, for other localities that they feel are more reliable.”

After the show of opposition from department heads and the city’s HR director, Abubaker and Gibson appear to be fighting an uphill battle to get to the five votes needed to pass their proposal.

“This is a city that has been plagued with the same issues for a very long time. I am not naive to think that change comes overnight,” Gibson said Monday as the body wrapped up another budget meeting without actually voting on any of the council’s ideas.

Some of the administration’s defenses of the budget’s compensation policies have been surprisingly blunt. So blunt, in fact, that Abubaker and Gibson have portrayed them as borderline offensive.

In one written response, the administration said that questioning pay raises for City Hall’s highest earners could overlook their unseen “financial burdens” and thwart a concept of equity based on “merit” and “contribution.” In another reply warning of the fiscal impact of expanding the city’s $20 minimum wage to contracted janitors and security guards, the administration seemed to imply there can be upside to low wages. Raising pay for those workers could hurt them, the administration wrote, by pushing them into a higher tax bracket or making them ineligible for government assistance.

Gibson asked the administrators to consider the totality of what they were saying.

“Yes, I would love to give you a 3% raise. But the person who comes and picks up the trash in your office makes $15 an hour,” Gibson said. “So when we’re talking about equity, I can’t hear the word merit.”

Applying the $20 minimum wage to contracted janitors and security guards would cost the city more than $3 million, according to the administration’s estimate. That idea has broad support among council members, but to pay for it the council would most likely have to find other ways to reduce spending or boost revenue.

All council members introduced ideas about where the city should spend more, but Gibson and Abubaker went further than their colleagues by attaching their names to proposed cuts and sharply questioning whether some spending was truly necessary.

The proposal to eliminate raises for high earners was one of the most significant spending reductions proposed by the council.

In a news release Monday morning breaking down what she called an “ethically hollow” stance by the administration, Abubaker said it sounded like a defense of “classist meritocracy” and the view that vast pay gaps are justified because City Hall’s highest earners are worth far more to the city than workers doing less-prestigious jobs like picking up the city’s garbage.

“Collective bargaining exists because of pay disparity and management abuse,” Abubaker said in her release. “If unionized workers receive modest cost-of living adjustments while non-union executives get five-figure merit raises and bonuses, then the conversation about ‘equity’ has been hijacked.”

A dispute over data

Using data the administration provided, Abubaker has been conducting her own analysis of city salary trends, flagging several major increases in the budgeted salaries for upper positions. For example, the salary for the city’s director of budget and strategic planning is going from $128,291 in fiscal year 2025 to $202,308 in fiscal year 2026. That’s roughly a $74,000 increase, worth almost 58% of the prior year’s salary.

The salary for the director of neighborhood and community services would rise by a similar amount, going from $128,290 to $191,012, an increase of almost 50%.

Abubaker has questioned what she called a “glut” of mid-level positions with good pay but vague-sounding titles like “policy advisor” and “management analyst.” Many of those jobs are also being budgeted for substantially higher salaries than they were the year before, well above the 3.25% envisioned for the across-the-board raise.

Abubaker, who works in strategic communications, has also taken issue with a plan to hire a new city press secretary at a budgeted salary of $165,000, when that person would report to a communications director with a salary budgeted at over $200,000. The previously budgeted salary for the press secretary role, which was formerly located in the mayor’s office, was a little less than $120,000.

“Are we in a hiring freeze or are we not?” Abubaker asked Monday, referring to Avula’s announcement in February that the city was taking steps to limit hiring for non-essential positions.

Budget Director Meghan Brown refuted some of Abubaker’s numbers, saying comparing last year’s salaries to this year’s proposed salaries is an imperfect metric because the budget reflects how much money is allocated for a position, not necessarily what the person in that role actually makes.

The large increase for her position, Brown said by way of example, happened because the city allocated a minimum salary for the job last year because it was vacant. The higher amount in the current budget, she said, reflects the salary she was given when the job was filled.

“You can’t just take two different years and compare them to have an apples to apples comparison,” Brown said.

Abubaker said the council can only work from the salary numbers it’s given.

“If this is the data I have, this is the data I have,” she said.

In a concession to the council, the administration has proposed around $1 million in additional budget cuts. That money would mostly come from eliminating jobs in the city election office, the anti-poverty Office of Community Wealth Building and cutting funding for the Richmond Resilience Initiative, a guaranteed income pilot program in which the city gives $500 every month to residents in extreme poverty.

It’s not clear whether the council wants to make those cuts. Councilor Ellen Robertson (6th District) said she was particularly troubled that anti-poverty programs would be first on the chopping block if the council wants to free up more money for its priorities.

But Robertson also assured city employees she would support raises for everyone.

“I don’t want you to walk away from here thinking that you’re not valued, that you’re not important,” Robertson told city employees. “The only reason why this city is what it is, is because of you.”

In an interview Tuesday, Abubaker said she doesn’t intend to back off, even though Monday’s meetings showed how much opposition she and Gibson are up against. She said she feels the administration is manipulating the budget process to try to make the council believe it has no power to do anything that doesn’t have the administration’s blessing.

It was inappropriate for department directors to “overtake public comment” on Monday to push for higher salaries, she said. That put influential City Hall leaders standing in the same line as children advocating for more money for positive youth programs at their high-poverty middle school and housing advocates asking for funding to ensure renters and mobile home residents don’t have to live in squalor.

“If that’s not an exemplification of how tone-deaf some people are to what is happening in this city, I don’t know what is,” Abubaker said.

The council will continue its budget discussions on Monday.

Contact Reporter Graham Moomaw at gmoomaw@richmonder.org