Gilpin Court redevelopment meeting turns testy as residents express skepticism about redevelopment plan

Before pews full of Gilpin Court residents and members of the larger Richmond community, Pastor Donte McCutchen prayed.

He prayed for collaboration. He prayed for clarity. He prayed for hearts to be softened. And he prayed that everyone might “work together to get things done from the people, with the people, for the people, and God, by the people.”

It was a hopeful start to the Richmond housing authority’s first public, in-person meeting since 2023 on plans to redevelop Gilpin, the city’s oldest and largest public housing community.

But over the course of the next two and a half hours at Greater Mount Moriah Baptist, the historic Black congregation that sits on the edge of Gilpin, those hopes ran smack into a wall of mistrust.

“It sounds like there’s a lot of money and a lot of land, and we ain’t getting none of it,” said community activist Art Burton.

“How do you sit in the position you’re in and see your people dismantled like this?” Umar Kenyatta of Black Wall Street Virginia asked Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority CEO Steven Nesmith. One resident called Nesmith a hypocrite; another pointedly asked how residents could trust him after the authority gave out $20 gift cards to tenants who came to City Hall to speak in favor of the redevelopment plan.

“You say people don’t come out,” one woman declared shortly before Nesmith called an end to the increasingly chaotic meeting just after 8 p.m. “You know why? Because we don’t like y’all lying to our face.”

Not everyone who showed up was against RRHA’s plans, which remain in their early stages.

Gilpin, which was built in the early 1940s, is “coming down, one way or another,” said Marilyn Olds, who is head of the Richmond Tenant Organization and the Creighton Court Tenant Council, and was relocated during the early phases of the ongoing Creighton redevelopment.

“Stop listening to them naysayers,” she said, even as she urged residents to keep abreast of the redevelopment process. “They want to fight RRHA and blind you to the truth so they don’t have no house to put us in.”

Charlene Pitchford, a Gilpin resident and vice chair of the RRHA Board of Commissioners, the local governing body for the public housing authority, argued that residents should “wait til the money gets to the table” before rejecting any plans.

“The commissioners have vowed and fought to make sure that if anything else — and I am a commissioner — anything else is wrong, we’re never going to let it go through,” she said. “But we’re going to support him right now because — hold on — only because it’s phase one. But if we find out anything different than what we have, we will not do that.”

Despite those urgings, the outpouring of suspicion and hostility from most of those who turned out to speak Thursday revealed the high hurdles RRHA will have to clear as it moves forward with its plans to rebuild the 1940s-era Gilpin, home to roughly 781 units and 2,000 residents. Besides getting support from Mayor Danny Avula, RRHA will need to meet numerous resident consultation and other requirements to secure federal approval of each phase of the project.

City Council has already shown some misgivings about how the authority has proceeded with its redevelopment plans. Most notably, Councilor Kenya Gibson, whose 3rd District includes Gilpin, has put forward an ordinance that would prohibit RRHA from moving forward with its redevelopment plans without Council authorization. Nesmith said he had met with Gibson, along with Avula and Council President Cynthia Newbille, for a “very constructive conversation” about the court.

To rebuild Gilpin, “people are going to be making some money,” Gibson told the people who assembled at Mount Moriah last week. “And we need to make sure that before anybody’s making any money, we’re doing right by the people who live here.”

Former Councilman Chuck Richardson said it was natural for residents to be “paranoid” about any relocation plans.

“Don’t come down here and pee on my back and tell me it’s raining,” he said. “That’s what these people are worried about, because that’s all Black folk have had to face.

Still, he called on residents to “stay calm and stay composed until you find out what’s going on.”

“If it’s good, you all should get behind it and support it,” he concluded. “If it’s a trick, you all who are presenting it should answer these questions.”

Even McCutchen, the pastor who voiced such high hopes at the meeting's start, aired concerns two hours in.

“I’m not necessarily opposed to redevelopment,” he said. “But I am opposed to the removal of Black families in the name of progress.”

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.

Replacement and relocation

Few people dispute that Gilpin, which was built in the early 1940s, needs to be rebuilt. A 2016 assessment of the physical condition of the court found that, like others in the city, it was far past its lifespan.

“Our public housing properties are functionally obsolete, meaning that they’re cost-ineffective and they have a lot of redevelopment needs,” RRHA’s former Deputy Director of Real Estate and Community Development Alicia Garcia told a City Council committee in an October 2021 presentation. “Full redevelopment would be the best option for our families and communities.”

Exactly how that should occur, however, remains controversial.

Since the 1990s, federal redevelopment programs like HOPE VI and Choice Neighborhoods have largely steered public housing authorities toward the creation of mixed-income communities in an effort to avoid creating large concentrations of poverty.

Nesmith has frequently cited that approach in speaking about Gilpin. “We have to be very careful,” he said Thursday. “We cannot reconcentrate poverty.”

At the same time, with federal funds for such projects declining, public housing authorities have increasingly turned toward partnerships with private developers, striking agreements that leave them with varying degrees of power over the units they create. In many of those scenarios, the new housing that rises to take the place of the old is no longer public housing exclusively owned and controlled by a public housing authority. Instead, while the new units are still reserved for extremely low-income families, residents get access to them through the use of a voucher — a tool that comes with a different set of protections for tenants.

That is the approach RRHA has taken with Creighton, where it has partnered with a developer called The Community Builders. It is also its planned approach with Gilpin. In October 2023, the RRHA Board of Commissioners authorized Nesmith to sign a master development agreement for Gilpin with HRI Communities, a developer who was also involved in the larger Jackson Ward Community Plan, a roadmap for the area that heavily focused on Gilpin’s redevelopment.

“It’s a public-private partnership,” Sherrill Hampton, RRHA’s current deputy director of real estate and community development, told meeting attendees Thursday. “It will not include public housing.”

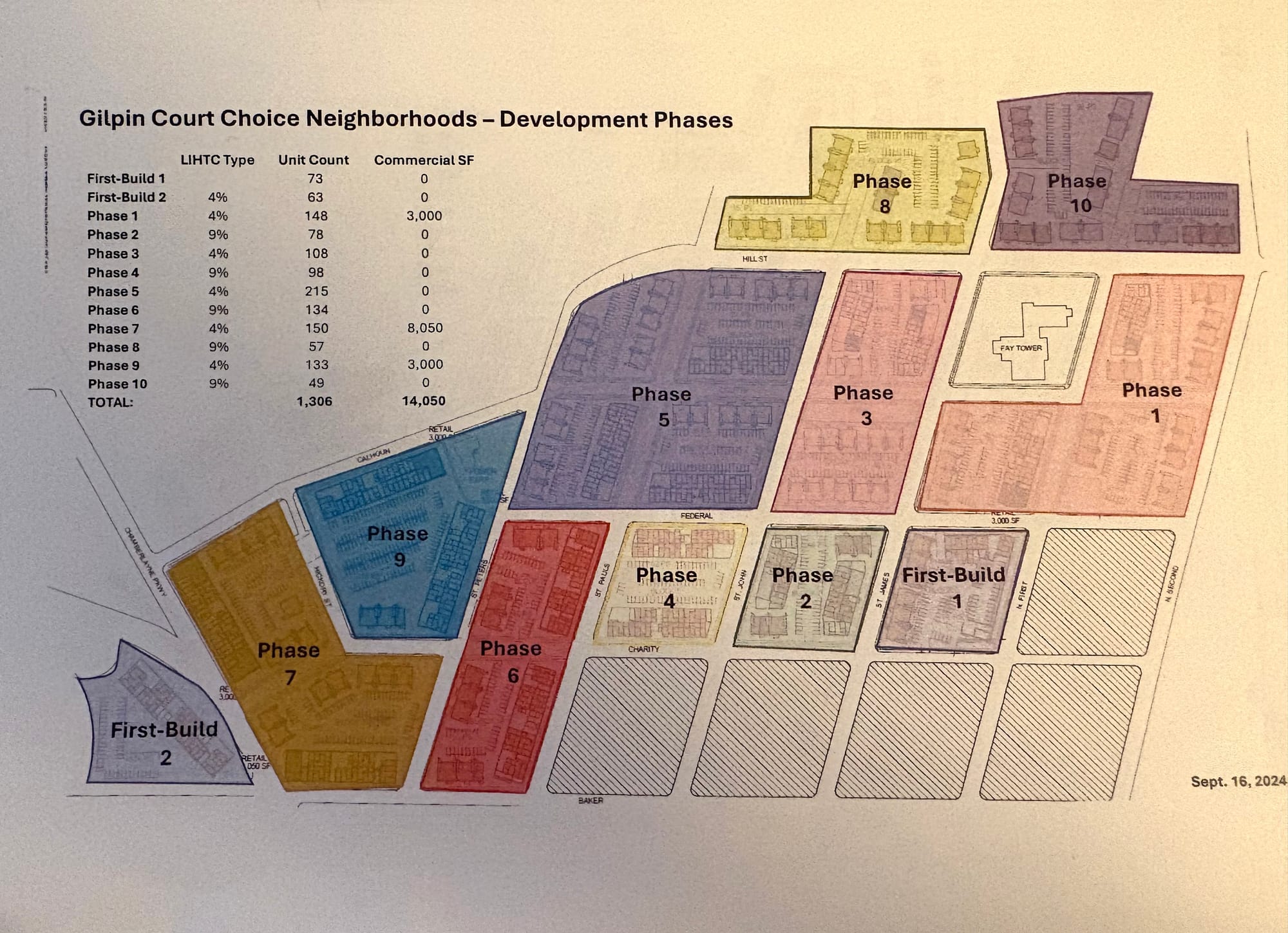

Documents handed out by RRHA Thursday indicate the authority intends to roughly follow the phased approach laid out in the Jackson Ward plan, building some replacement housing first and then beginning relocations, demolitions and rebuilding over the course of 10 phases.

The earlier document, which was completed using a federal grant in 2023 but has yet to be approved by City Council, called for the development of roughly 1,300 rental units as well as housing intended for purchase. Gilpin’s existing 781 units would be replaced “one-for-one” through 450 units located on the footprint of the current community and 331 units owned by landlords around the city. All of the “replacement” units would be occupied using project-based vouchers, or vouchers tied to a specific location.

The plans detailed Thursday call for the gradual development of 1,306 new rental units at a range of price points on the existing Gilpin Court site. RRHA officials said roughly one-third, or 450 units, would be set aside as replacement housing; one-third would be “affordable,” or up to 80% of the area median income; and one-third would be market rate.

Hampton cautioned that “those numbers can change.”

“As we develop each phase … we will come back and be able to give exact numbers for that,” she said. “But this whole housing market is fluctuating. The financing is fluctuating, so that’s why we are giving estimates to you right now.”

That uncertainty, though, has left some people unconvinced that residents will have a place to go as redevelopment occurs.

“The train is coming fast, and it sounds like to me only 450 residents from Gilpin Court are going to get on it,” said Burton. “That’s 350 that still need a place to live.”

While Virginia law prohibits landlords from discriminating against people with vouchers, in practice, many find workarounds such as requiring tenants to show proof they have three months of income saved up or asking for hefty security deposits. Nesmith has previously acknowledged that many landlords won’t accept voucher holders as tenants.

Richmond Development Corporation

Particularly concerning to many of the people who turned out for the Thursday meeting was the role the Richmond Development Corporation will play in the project.

Minutes from RRHA Board of Commissioners meetings indicate the RDC was first created as a nonprofit subsidiary of the housing authority in 1981. Such an entity isn’t unusual: Numerous public housing authorities across Virginia, including in Charlottesville and Alexandria, operate subsidiaries in order to get more flexibility in their redevelopment plans.

But precisely what role the RDC would take in the Gilpin redevelopment has been a source of major confusion, particularly after Nesmith put forward a resolution to transfer the Gilpin properties — although not the land they sit on — to the nonprofit this spring. The resolution failed.

“All I want to know is, if this plan is so good, it’s so tip-top, so intact, so together, so snatched, why are we creating a whole RDC to put the plan under there?” asked Gilpin resident Charlene Riley.

Angela Fountain, a spokesperson for RRHA, said in an email that “under the new plan to redevelop Gilpin, RRHA is not transferring all of Gilpin to the RDC.”

“The RDC will serve as the investment partner to the redevelopment efforts,” she said in an email. “Specifically it will take in today’s dollars over $466 [million] to redevelop all 10 phases. RRHA is not structured to either go out and raise revenue or receive funding under a public/private partnership to finance all phases of Gilpin Court.”

In an application the housing authority submitted to the state’s housing agency earlier this year in search of low-income housing tax credits, the RDC is a managing member of a new entity set up in partnership with HRI Communities to build 56 units of housing adjacent to Gilpin Court into which a small number of residents can move ahead of any relocations.

Kyla Goldsmith-Ray, a spokesperson for Virginia Housing, said the project had been awarded tax credits this June and would have until Dec. 31, 2027 to go into service. However, she added, that deadline can be extended “if necessary.”

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.