For many neighborhood associations, Richmond’s zoning overhaul is too much, too fast

Duplexes by right. Setbacks. Unlimited mixed use.

Ask any of Richmond’s several dozen neighborhood associations what they think about the city’s ongoing overhaul of its almost 50-year-old zoning code, and you’re likely to get an earful.

“If you ask five different people, you may get six different responses,” said Mark Olinger, president of the Church Hill Central Civic Association and the former director of Richmond’s Planning Department. “There are people in my neighborhood who say the more density the better. And there’s people like me who say, ‘Let’s be conscious of the character.’”

Neighborhood associations, as voluntary groups of residents, have no legal role in the code refresh process. But the city relies heavily on them to act as a bridge to residents, gathering feedback on proposals, sharing information and even brokering deals on projects where a developer and community members are at loggerheads. As a result, the groups can wield a significant amount of influence.

Exactly how they feel about the code refresh varies. A few say they back its vision of creating denser neighborhoods with a wider array of housing opportunities. For some, the idea of allowing duplexes by right on all residential parcels is a top concern; for others, it’s potential displacement of lower-income residents or the possibility that buildings with historic or cultural value could be demolished.

Still, in lengthy interviews with eight neighborhood associations, and in letters sent by groups to the Planning Department, two concerns arose repeatedly: That the first draft maps call for too much density and that the zoning overhaul is happening too rapidly.

“We feel like there’s way too much density being proposed and densities that will lead to demolition if there aren’t some protections put in place,” said Melissa Savenko, who chairs the Fan District Association’s zoning committee.

That view isn’t universal — but it is widespread among associations. And even among those groups like the Church Hill Association or the Oak Grove Neighborhood Association that have a comparatively more positive view of the code refresh, there was broad agreement that the rollout of the proposal has been flawed, relying too much on technical knowledge the public lacks and failing to make a sufficient case for why changes are necessary.

Patty Merrill, president of the Westhampton Citizens Association, recalled one meeting her group held with Deputy Director of Planning Marianne Pitts to discuss the code refresh.

“I fully expected people to be more in question mode,” said Merrill. “She came with maps and was ready to answer specific questions. And there were a lot of people who were like, ‘I don’t even understand why we’re doing this.’”

“Obviously something did not go correctly,” said Suzanne Lee, who heads the Church Hill Association’s Historic Preservation and Land Use Committee. “And I can’t begin to analyze what it was.”

She hazarded one guess: “To the uninitiated, this looks very, very complicated.”

Will density destroy character?

Because they change the rules of how development can occur and land can be used, large-scale zoning overhauls are almost always contentious. In Virginia alone, recent efforts to encourage the development of more housing by loosening zoning restrictions have sparked lawsuits in Charlottesville, Roanoke, Arlington, Alexandria and Fairfax County.

In Richmond, rewriting the 1970s-era zoning code was one of six “Big Moves” the city flagged in its 2020 master plan. Planners have largely pitched the refresh as a necessary effort to bring outdated rules in line with how residents live today and foster greater density amid shortages of affordable housing.

The goal of reducing nonconformities — situations where existing properties don’t comply with the current zoning and couldn’t legally be rebuilt as-is if they burned down — has been largely uncontroversial.

“The code needs to be updated. I think that that is a fairly clean and clear need,” said Janet Woodka, president of the Manchester Alliance. “There are provisions in the code that just don’t reflect current realities.”

The density piece is where it gets dicier. Many neighborhood groups are skeptical of claims that increasing housing supply will alleviate the affordability crisis, arguing that outside of Richmond’s Affordable Housing Performance Grant Program, many of the new units built over the past five years have been market-rate or luxury.

“From a general perspective, we’re fine with additional density,” said Savenko of the Fan District Association. But, she continued, “I don’t think that the plan achieves what they think or expect to achieve in the sense that there's a lot of discussion about density equals affordability and a lot of talk about the affordable housing crisis. And it's frustrating to me because they're kind of conflating a lot of things.”

At the same time, groups say that by allowing greater density in most neighborhoods, the first zoning proposal threatens to erode the character of what already exists and is cherished by residents.

“I keep sensing they’re trying to make us all … kind of be the Fan,” said Olinger. “I moved into the Oakwood neighborhood because I liked the character of my neighborhood.”

One flashpoint is the so-called duplex proposal, a provision in the first draft that would allow the construction of two units by right on all residential lots. That extra unit would be in addition to the existing right of owners to build an accessory dwelling unit on nearly all residential lots, a change City Council approved in 2023 as part of an effort to increase housing supply.

Opponents of the duplex proposal contend that far from offering the “gentle” increases in density that backers tout, the idea could lead to a radical reshaping of neighborhoods with double the number of residents that previously existed.

“We’ve barely let that effort have any opportunity to either demonstrate that it works or not demonstrate that it works,” said Merrill of the Westhampton Association. “And now we have to increase the density yet more.”

Merrill has pushed the city to get rid of that provision, saying it could help clear the way to more support from neighborhood associations.

“If you look around at who’s brought the litigation in the other jurisdictions who have had a problem with this, it’s been over that issue,” she said. “So I think it would take the temperature down significantly.”

The possibility of eliminating the duplex provision, though, is already meeting determined opposition from some quarters. Nonprofit affordable housing developers say the duplex proposal can significantly reduce construction and therefore housing costs and ensure increases in density occur equitably around the city. Other proponents dismiss the worry that density will swiftly double due to duplexes, pointing out that hasn’t occurred in other cities that have made such a change.

Besides duplexes, pro-density proposals to eliminate minimum lot sizes, reduce minimum lot widths and increase the percentage of a lot that structures can cover have caused heartburn among some neighborhoods where homes and yards tend to be large and green.

“Code refresh, just with its tremendous amount of density it’s proposed, just tends to barrel through neighborhoods,” said Stephen Weisensale of the Ginter Park Residents Association, which has become one of the most vocal critics of the overhaul.

Residents moved to those areas because they found those features appealing, the groups say, and they may leave if that character changes.

“People live in Ginter Park for a reason,” said Katie Cortez, who serves on that association’s planning and zoning committee. “They don’t necessarily want to live in the Fan or Church Hill. They want the yards. They want the space.”

Today, much of Ginter Park’s zoning requires single family homes on lots that are at least 20,000 square feet in area and 100 feet wide. The first draft map would convert most of that into the new RD-A zoning, which requires lots to be 90 feet wide but gets rid of any lot area requirement.

Olinger worried some lot width minimums have dipped so low they will prevent owners from constructing anything but the same house type. In the proposed RD-C district, he pointed out, lots only have to be 25 feet wide, a low threshold that could encourage developers to buy up existing lots and pack as many narrow, cookie-cutter homes into them as possible.

“You can do a lot in a 30-foot-wide lot. You can’t do much in a 25-foot-wide lot,” he said. “I think it’s important that people have a little bit of room for some open space.”

“The things that make a neighborhood age well,” he concluded, “are absent from RD-C.”

In Oak Grove, a neighborhood of smaller residential lots on the Southside that could largely be rezoned to RD-C, Charles Snellings, president of one of the two civic groups that represent the area, appeared less concerned about that aspect of the rezoning.

“The plan has a lot of good pieces,” he said, pointing to the greater density it calls for along the Richmond Highway and Commerce Road corridors that flank Oak Grove’s residential core.

Allowing six- or 13-story mixed-use development along those corridors could put services in better reach of residents who currently have to drive to restaurants, pharmacies and grocery stores, he said, although he worried that without parallel efforts by the city to fill those spaces, Richmond could end up with even more vacant, blighted properties like the nearby Brady Square.

“The people who are so vehemently against [the code refresh] that they are like, ‘Get rid of the whole thing, we don’t want it, we don’t want it’ — I don’t know that they’re actually seeing and taking time to dwell and be in and exist in some of these neighborhoods that would truly benefit from it in such a needed way,” Snellings said.

Even for groups like the Manchester Alliance that have been receptive to density, the first draft raises questions. Why the city would allow unlimited mixed use, a designation with no height limits, immediately adjacent to the James River was a point of confusion for Woodka, as were decisions like allowing more density on parts of Hull Street than along the wider and more heavily traveled Cowardin Avenue.

Nor, said both she and Savenko, is it clear what the limits of density are.

In Manchester, “we have had a lot of growth,” said Woodka. “At what point is the growth sufficient?”

Demolition and displacement

Neighborhood character, of course, can be a matter of opinion. One person’s stable, close-knit community can be another’s exclusive enclave. In meetings this fall on the city’s proposed Cultural Heritage Stewardship Plan, some younger speakers expressed reservations about the idea of tightly defining a neighborhood’s character based on what exists at this moment in time.

“Hardline, neighborhood-level preservation by committee is antithetical to urbanism,” said one resident who identified himself only as William.

Less subjective are two potential impacts that neighborhood groups are concerned could result from hikes in density: demolition and displacement.

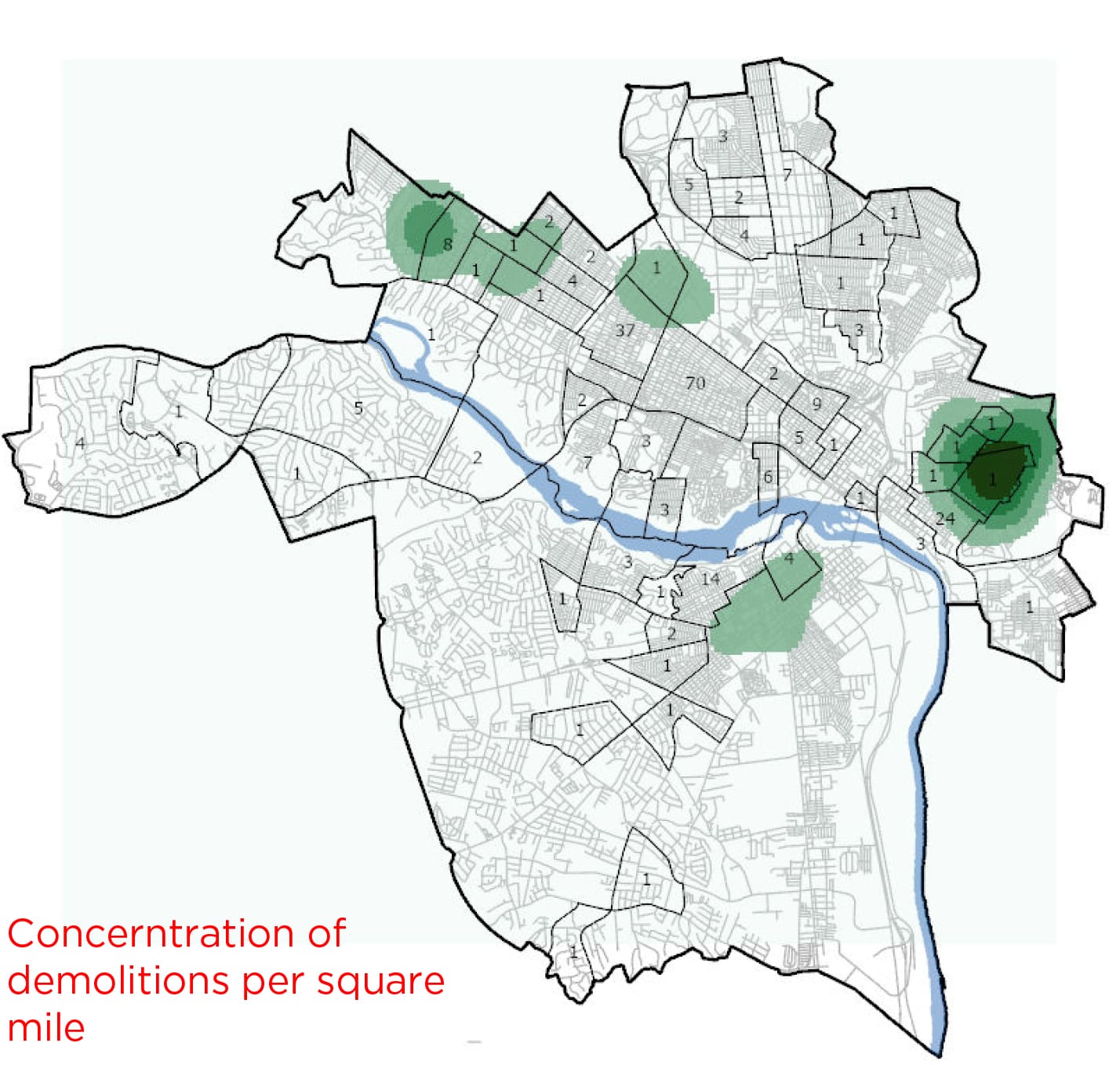

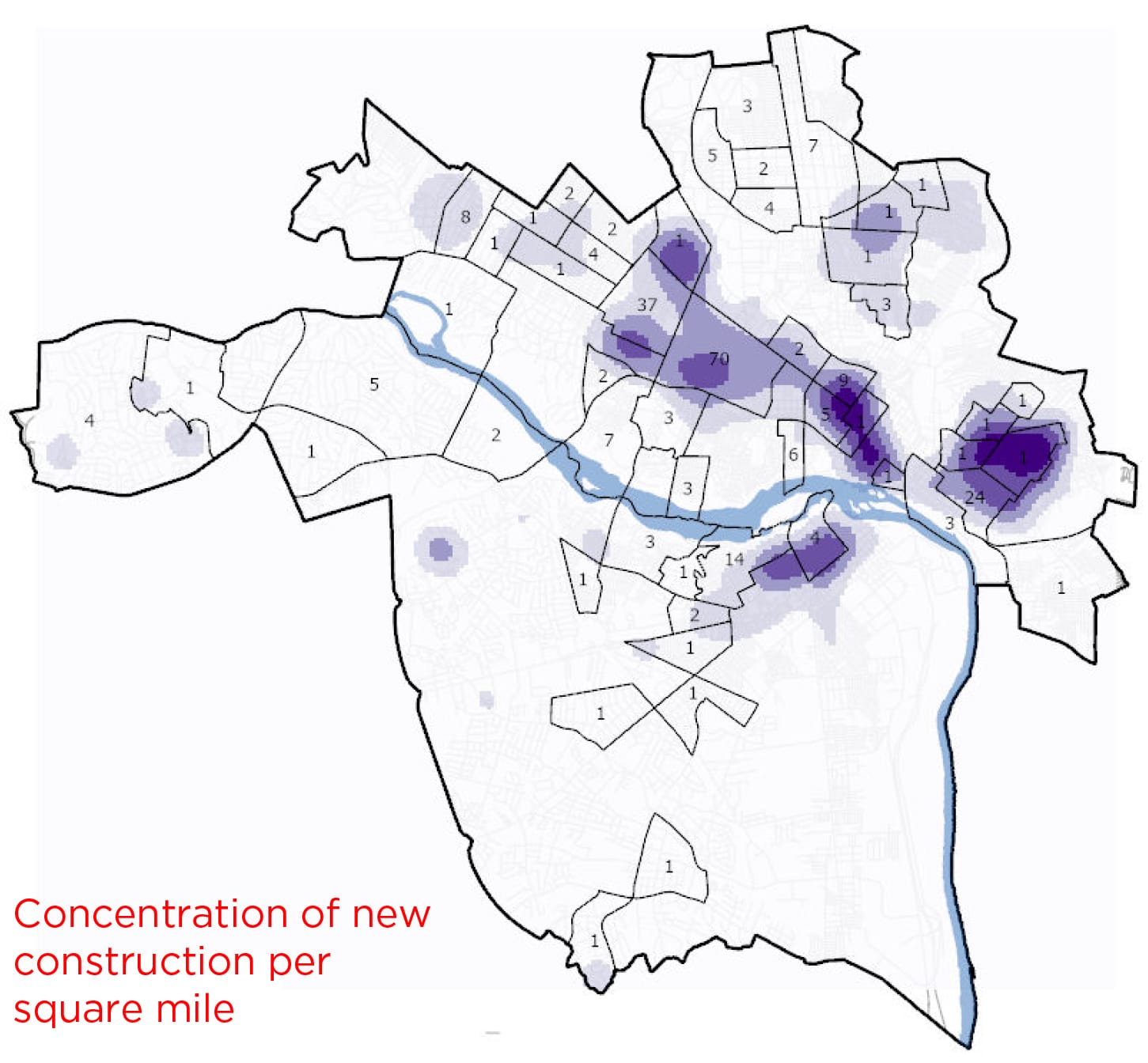

Even prior to the code refresh, some of those trends are already evident in parts of the city where developers are snapping up lots and remaking them as duplexes, denser groups of single family homes or multifamily buildings. Demolitions have been particularly common in the East End, according to mapping by the Planning Department.

Right now, almost every project that increases density requires the developer to obtain a special use permit through a lengthy process involving public hearings before the Planning Commission and City Council. While the code refresh won’t do away with SUPs, it will reduce their numbers by allowing more development by right.

Savenko, who is also a residential real estate agent, said planners need to be aware of what incentives they’re putting in place as Richmond’s real estate market remains hot.

“The fundamental concern is people are going to come in and start tearing down homes,” she said. “Now in the past you can say, ‘Well, that doesn’t make sense. Economically, nobody is going to come buy a $1 million home, tear it down and put up another home with an ADU.’”

That equation changes if suddenly someone can replace that home with a six- or 12-unit apartment building by right, she said. In desirable neighborhoods like the Fan where builders can market their units for high prices, teardowns can suddenly make sense.

Some protections are available to neighborhoods if enough of their residents are willing to get an Old and Historic District designation from the city. But communities can be reluctant to go down that path because of the additional requirements it places on property owners, who then have to get approval from the Commission on Architectural Review for any changes to a building’s exterior or demolitions.

“My concern is, if you’re not in an OHD, you’re screwed,” said Olinger.

Jerome Legions, head of the Carver Area Civic Improvement League, said it’s essential for Richmond to incorporate historic protections like those envisioned in the still-pending Cultural Heritage Stewardship Plan into the rezoning. Otherwise, he said the new rules will give developers “carte blanche to do whatever they want to do for the most part.”

While the worry in historic neighborhoods is that density will drive demolitions, fears in less prosperous communities center on displacement. The long stretch of affordable units along Chamberlayne Avenue has already become one flashpoint, but it isn’t the only one.

“There's a real fear and a real concern that I even share of our seniors being forced out,” said Snellings. “And you know, on the flip side, as a public servant in public education, I worry about being pushed out of this neighborhood myself, if I'm honest with you.”

In talking about both demolition and displacement worries, members of numerous neighborhood groups urged the city to consider using other tools to reduce potential negative impacts. Some pointed to the Charlottesville zoning code’s use of an anti-displacement overlay that incentivizes developers to either keep existing structures or develop affordable replacements; others said it’s critical for the city to convince the General Assembly it needs broader inclusionary zoning powers that could let it mandate that developers set aside a certain percentage of units as affordable.

Without additional protections, groups fretted that the rewrite will simply mean they have less of a voice on neighborhood change as more projects that previously would have had to go through the special use process are able to happen by right.

“Those SUPs create community engagement,” said Legions. “It forces conversations between the developer and the community.”

But while many of the neighborhood associations prize the forum the SUP process grants them, and the negotiations it allows, others like the Church Hill Association said the current situation is “burdensome.” Over the past five years, the Planning Department has handled an average of 110 SUPs annually. While some are highly controversial, triggering public outcry and multiple hearings, others cause no pushback at all — but still require the same investment by the city.

“They just add time and money and delay and the need for legal assistance to the process,” said Lee. “And so it makes a lot of sense to have the kind of standardization that takes the burden of SUPs away.”

‘Something that’s being done to them’

Exactly how much members of the public will be able to influence the code refresh is, for many neighborhood associations, a sore spot.

The Planning Department has repeatedly said the second draft, which will be released next week, will include changes.

“This is an iterative process. We expect and encourage feedback from our residents,” said Planning Director Kevin Vonck in an email. In meetings, he’s already told some groups that lot coverage maximums — which govern how much of a parcel can be covered by buildings — will be reduced in the second draft following complaints. He made a similar pledge that change will occur in an email this September to the Oregon Hill Home Improvement Council in response to a scathing critique from that group of the first draft.

“The goal is to bring the code closer to a place where the majority can agree upon what buildings and uses should be permitted ‘by right’ versus those that should still require special legislative approval,” he wrote.

But many neighborhood associations told The Richmonder they believe the city has already fallen far short when it comes to public engagement.

Despite the roughly 50 meetings the Planning Department has held on the code refresh, many of them in the form of visits to individual neighborhood associations, groups said the city has spent too much time reacting to questions and too little time explaining what it wants to do and why in a way that laymen can understand. Surveys and informational boards at open houses have been laden with jargon, they said, and often depend on people understanding zoning more broadly — which most people don’t. Too few events have prioritized putting people around a table to simply talk about what they want from a rezoning.

“I think part of their frustration and anger is that they don’t understand,” said Merrill of the Westhampton Citizens Association. “This feels very much like something that’s being done to them from a city they don’t trust.”

Trust, or a lack thereof, came up repeatedly in interviews.

“We all know there’s distrust in the city. Legitimate or not, there is,” said Woodka of the Manchester Alliance. “People aren’t engaging because they think, ‘Why should I go and spend all this time and go to all these meetings, and in reality, they're going to do what they want to do anyway?’ I personally don't feel that way, but I think that there is a good chunk of the population that feels that way.”

Legions put that outlook even more plainly: “They’re going to make something happen regardless of the input.”

Nothing has provoked more mistrust than the Zoning Advisory Council, a subcommittee of the Planning Commission that is charged with working with the city’s consultants to help guide the refresh.

While the ZAC is solely advisory and has no formal voting power, it has so far been the primary public forum for discussion about the rewrite, and its recommendations will shape what eventually goes to the Planning Commission for its consideration.

Nearly every neighborhood association who spoke with The Richmonder said they believed developers and development-related interests had too big of a presence on the body. Earlier this fall, the Planning Commission expanded its membership from 17 to 21 seats in response to complaints from residents, but groups said it still fails to include key representatives.

“There’s no preservationist people, there’s not even residential real estate people,” said Merrill. She pointed out that during ZAC discussions, architect and advisory council member Dave Johannes has several times piped up to say that certain proposals are impractical from a building standpoint — valuable feedback if the city is to produce a workable document.

“You want some of those people there,” she said.

Neighborhood associations themselves aren’t always representative either, some members acknowledged. Different groups have different capacities, and older and wealthier residents tend to have louder voices than younger, less affluent ones thanks to more time and resources. Some residents who favor change may also be reluctant to air that opinion if their neighbors have already come out in opposition.

Furthermore, said Woodka, “what do you do in a neighborhood where there’s no one, there isn’t even a neighborhood association? There are vast parts of the Southside that have no neighborhood association, and so of course they’re not being represented.”

With so much at stake, numerous groups said it’s crucial to slow down the refresh process. Instead of rushing to get the rewrite passed by the winter or spring of 2026, they said the city needs to take the time to craft a strong plan and bring communities on board with it. Olinger has floated the idea of the city focusing on corridors and priority growth nodes now and putting off a residential rezoning until later.

“I would hate to see us focused on a deadline rather than getting it right,” said Woodka.

But Vonck has said the speed with which Richmond is moving is in response to City Council’s 2023 declaration of a housing crisis and Mayor Danny Avula’s inclusion of housing as one pillar of his Mayoral Action Plan.

“That means we need to act quickly,” he said. “It puts a lot of pressure on us to make sure we are being thorough, but the directive is to do this sooner than later.”

As the process continues to move forward, groups have made it clear that a lot is riding on the second draft. Some, like Lee of the Church Hill Association, are more optimistic about what the city will produce.

“I have absolutely no doubt that the city is listening,” she said. “There was no expectation that the first iteration would nail it perfectly.”

Others are a little more cautious, although Weisensale said he’s “trying to not get all pitchfork, fire and brimstone about this thing” until the city has a chance to revise its proposal in response to public input.

“The big thing for a lot of us is what’s going to come in November,” he said. “That’s going to tell us how much Planning is really listening.”

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org