Exactly 100 years ago, the Church Hill Train Tunnel collapsed as men worked inside. The true death toll will never be known.

For 100 years, steam engine number 231 has slept beneath the unstable slopes of Jefferson Park.

The locomotive, buried under thousands of pounds of dirt in a tunnel sealed up by the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad at both ends, is a relic of one of the most dramatic episodes in Richmond’s modern history.

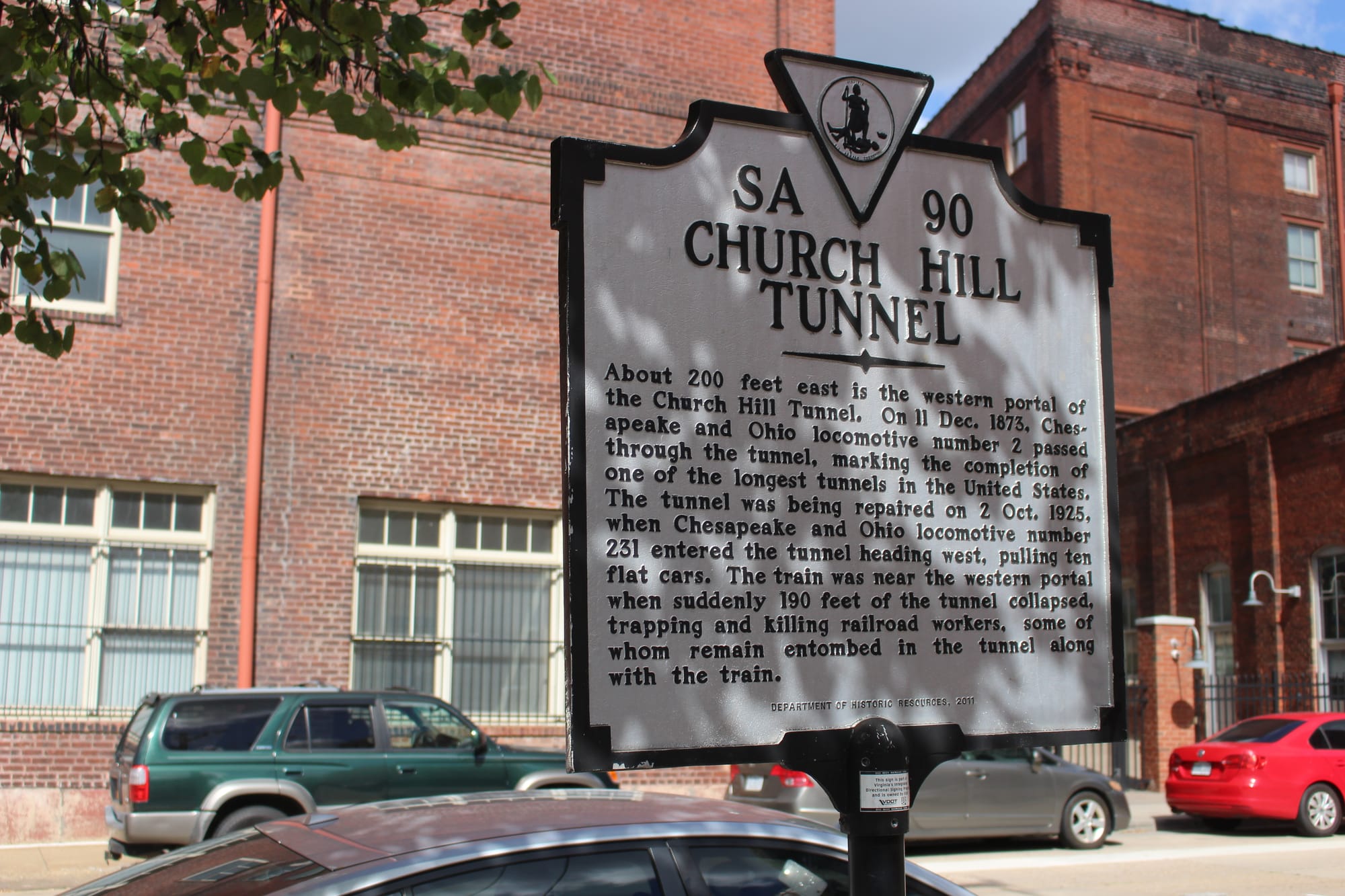

Exactly a century ago, sometime after 3 p.m. on Oct. 2, 1925, a railroad tunnel that stretched 4,000 feet from 19th and East Marshall streets to 31st and East Grace streets collapsed. When the roof came down in a shower of bricks, some 200 men were inside the tunnel, which they were in the process of widening and reinforcing.

Incredibly, nearly all would fight to safety through thousands of feet of darkness, debris and a scalding cloud of steam produced when the falling earth and masonry crushed the steam engine’s boiler.

At least two men — probably four, and possibly even more — were not so lucky. Engineer Tom Mason, the driver of the steam engine, was pinned in the cab by debris and the reverse lever and not recovered until Oct. 11. He was buried in a coffin with the number 231 painted on its side. Fireman Benjamin F. Mosby escaped but was so badly scalded that he died seven hours later at Grace Hospital (now an apartment building at West Grace and Monroe streets).

The other presumed losses have long been identified as a Richard Lewis and an H. Smith, likely Black day laborers on the site, but their bodies have never been found.

“Since the recordkeeping was not very formal and most of the workers were day laborers, we may never know if and how many other men were killed in the collapse,” wrote authors and ghost tour operators Scott and Sandi Bergman in an account of the tragedy.

Warning signs

In the months and years leading up to the collapse, there had been plenty of warning signs.

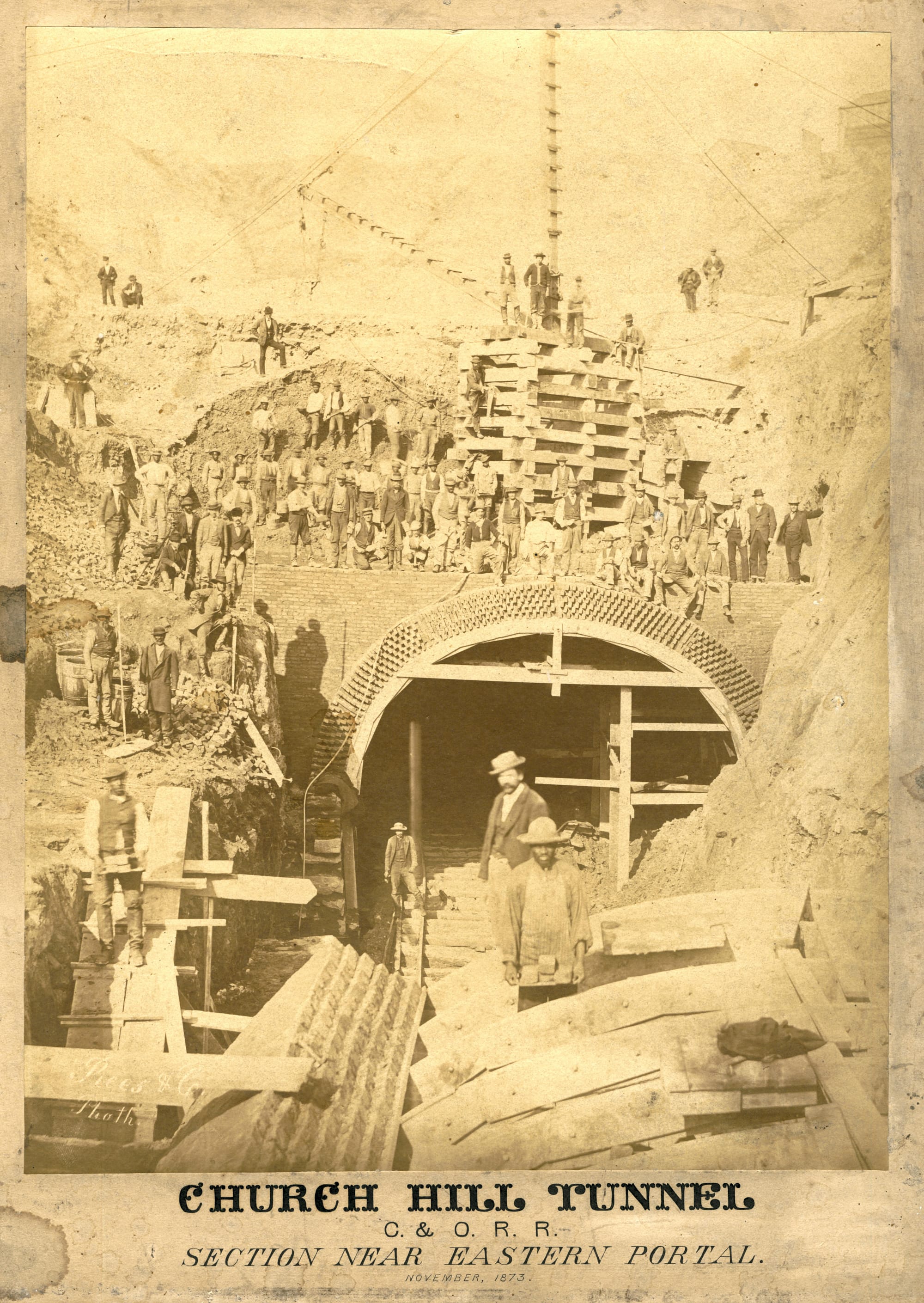

The C&O broke ground on the tunnel, which was used as a connection from its main tracks to the docks on the James River, in 1872. The first death occurred within four months, when “a huge piece of earth fell without warning from the roof of the excavation” and killed assistant engineer James M. Bolton, according to a contemporary account from The Richmond Dispatch.

Numerous other workmen would die during the construction, some from falls or other worksite accidents typical of the time, others directly linked to the instability of the earth through which the tunnel was being cut.

Nor were the dangers limited to the laborers. On Jan. 13, 1873, as work progressed, large cracks appeared on Church Hill over the path of the tunnel, and the city hastily evacuated several of the buildings along its route.

The next morning, according to law professor and historian Walter S. Griggs, Jr., who extensively studied the tragedy, a chunk of land 120 feet long and 30 feet wide sank 20 feet, carrying several houses along with it — including the study and kitchen of the rectory at St. John’s Church.

Engineers at the time were well aware of the instability of the soils, made up of a combination of clay and the slippery and easily saturated blue marl.

The clay “has the habit of caving in at the most unseasonable times in the most disagreeable manner,” wrote Scientific American in an item about the Church Hill Tunnel in January 1874. “The contractors long ago gave up, and the railroad company was compelled to take the work. Six or seven men have been killed, while the repeated cavings have undermined many houses over the line, which is three quarters of a mile long, and is not yet open.”

Despite the cost of constructing the tunnel in both lives and money — the city of Richmond had appropriated $200,000 for the project, equivalent to about $5 million today — it only operated for about 25 years. It was closed in 1902 after a steel viaduct was constructed to the James River and Main Street Station opened.

Collapse

As cargo volume increased in the following years, the C&O again began to eye the Church Hill Tunnel as a solution to easing traffic, and in 1925 workers started the process of reinforcing and perhaps enlarging it (although the record remains spotty on whether an expansion was planned).

On Oct. 2, Mason climbed into steam engine number 231 and drove it and 10 flatcars into the western end of the tunnel at 19th Street. According to accounts from the time, the workmen began removing material from the sides of the tunnel as part of an effort to reinforce its walls with concrete rings.

Later, a city of Richmond inspector would speculate that the removal of the blue marl soil, which already allowed steady streams of water to flow into the interior, undermined the tunnel’s integrity. With the structure weakened, the intense vibrations of the steam engine triggered the collapse.

Another assessment, delivered to the Virginia State Corporation Commission just days after the catastrophe, attributed it to a failure to use horizontal braces of walls that were “known years ago to have been defective.”

Whatever the cause, “just before the crash the masonry in the tunnel gave an ominous warning of the catastrophe impending,” wrote the Richmond Times-Dispatch in a front-page account of the tragedy on Oct. 3.

“A few bricks in the roof fell with a splash into the pools of water which spotted the earthen floor,” the paper continued. “The bulbs on the line of electric lights flashed twice. There were yells to run clear of the threatening cave-in and the workmen dashed along the track, a few toward the adjacent western end, but the majority into the dark pit which led to the eastern exit. Then came the crash of cracking timbers and the roar of falling earth and broken masonry.”

Even from a distance the scale of the destruction was evident. Up on the Jefferson Park hill, a fissure roughly 100 feet long and 20 feet deep opened, swallowing up within it a sidewalk and concrete stairway.

In the aftermath, observers would note two lucky escapes: The collapse occurred shortly after children heading home from school had already crossed through the park. Furthermore, because it happened beneath a park, no houses were dragged into the chasm along with their inhabitants.

Rescuers would work 10 days to reach Mason’s body, hampered by continued cave-ins and the appearance of more cracks in Jefferson Park. Efforts to find Richard Lewis continued through at least Oct. 16.

A coroner’s jury would subsequently find that Mason’s death was caused by the negligence of C&O railroad officials in ensuring that the tunnel was properly braced during work.

In 1926, the C&O filled up the tunnel with sand and sealed both ends with concrete, leaving the train entombed beneath the hill.

There it has lain ever since. In 2006, the CEO of Gulf and Ohio Railways attempted to remove the train by first pumping accumulated water out of the tunnel, but work was halted when officials discovered the team had failed to acquire permits for the work and concerns were raised about destabilizing the hill. No additional efforts have been made.

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.