Does anybody want this historic home in Bellevue? If not, RPS is ready to tear it down.

Towards the end of a recent town hall at Linwood Holton Elementary, roughly 40 attendees were asked to raise their hands if they wanted to see the historic building located on the school’s property saved.

About a third of the group did so, including 71-year-old Rich Souser, a local resident who has lived in the area for the last 40 years and has seen the building go through several phases.

“We’ve seen it when it was maintained and painted and wasn’t leaking and didn’t have weeds all around it,” he said. “And I would like to see it preserved.”

But Richmond School Board member Ali Faruk (3rd District) – who represents the district the building resides in – said RPS has limited funding, and it shouldn’t go towards preservation when there are urgent needs in active school facilities.

“At the risk of becoming the target of their ire, I would rather see that this structure be demolished and that the land be used to supplement the play space that is actively used,” he said to Board members at a meeting earlier this month.

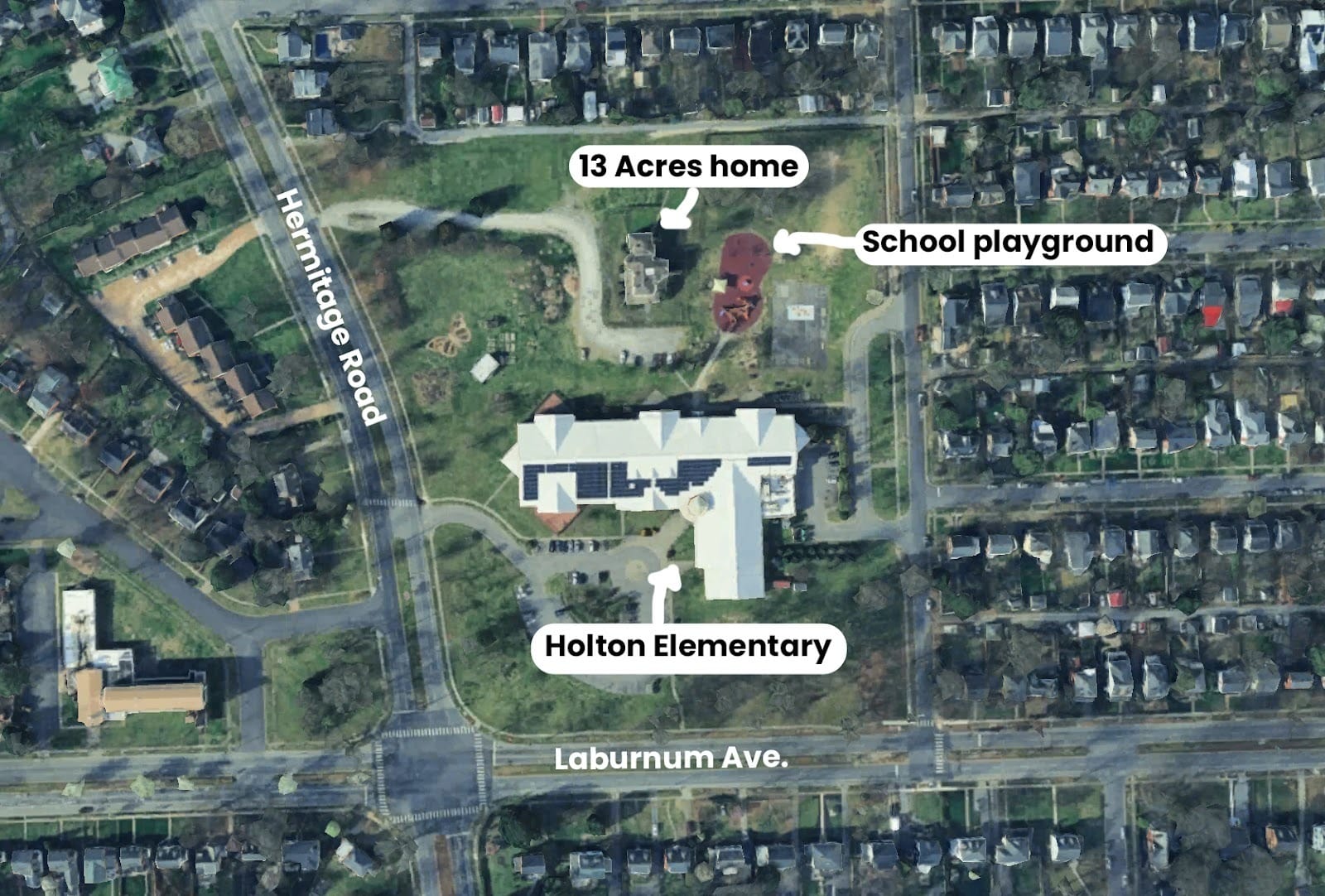

The structure in question is the Thirteen Acres School building, a 140-year-old, two-story house owned by Richmond Public Schools residing behind Holton Elementary in Northside’s Bellevue neighborhood. The building – once used for special education and office space – has remained vacant for nearly 20 years with no upkeep, resulting in its deterioration.

A school board committee recently recommended a one-year “sunset” period for the building. That would allow community members an opportunity to offer potential solutions, including moving it to another site. If nothing happens, the division would demolish the building and keep it as more green space for students attending Holton Elementary.

'A beautiful house in a significant state of disrepair'

The Thirteen Acres School was originally constructed as a brick farmhouse around 1885, predating Northside’s streetcar suburban developments. It gets its name from being on a 13-acre piece of land.

The Virginia Methodist Home for the Aged – a system of senior living communities now known as Pinnacle Living – sold the property to the City of Richmond in 1967, after which it was used as a special education school, space for municipal offices and later a school for students with mental health disorders.

The division had planned to create an elementary school in the building, but residents at the time opposed the plan, arguing that the building’s location was too close to traffic for walking students. In 1999, Richmond Public Schools built the Linwood Holton Elementary School right in front of the Thirteen Acres building, before it eventually closed in 2007.

The building is one of the oldest in the Hermitage Road Historic District, which is listed on the National of Historic Places and the city’s Old & Historic Districts. Thirteen Acres was later placed along with three historical schools on Preservation Virginia’s 2023 list of most endangered places in the state. Preservation Virginia is a statewide nonprofit focused on preserving historic places.

As time passed, the building continued to crumble. Currently, the building is wrapped in metal fencing, likely due to animals that have entered the premises where graffiti is visible on the inside. It’s not difficult to see the deterioration outside the building either, as peeling paint, decaying wood and broken window panes riddle the property.

Dispute over available options

The Richmond School Board’s Facilities & Vacant Properties Committee recently presented its first set of recommendations for the division’s empty buildings. Committee chair Stephanie Rizzi (5th District) described the Thirteen Acres house as being “in horrible condition” and “deemed unsafe.”

“The biggest problem with this one is that this building is literally in the worst shape you could imagine. Like, it’s about to fall down. I don’t know if it’s even salvageable,” she said.

Rizzi said that residents and historical preservation groups “have some attachment” to the building, but have not made much effort to do anything with it. As a result, she said the committee recommended sunsetting the building for a year to give community members an opportunity to offer actions for the building.

But some historic preservation group leaders deny the notion that the building is not salvageable, and said that options to restore the building have been presented to the Board.

In 2021, board directors of the Bellevue Civic Association sent a letter to the School Board declaring their opposition to demolishing the building, requesting that the Board repair the fencing around the building to properly secure it from trespassers, and for the building to be transferred to the Richmond Land Bank for appropriate reuse possibilities.

Thirteen Acres “is in a deplorable state of neglect,” they wrote. “The building … has effectively been abandoned by its owners, the Richmond School Board.”

Historic Richmond, a preservation nonprofit, sent a lengthy list of options to the School Board two years later, varying from school use to residential use and relocation.

“The first step we need is to have those conversations,” Cyane Crump, president of Historic Richmond, said in an interview with The Richmonder. “I’m not sure that those conversations have really happened since the ideas were floated in 2023 for Thirteen Acres.”

Those options were backed by the Hermitage Road Historic District Association, the historic district where the structure is located.

The district “has long advocated for the preservation of the historic Thirteen Acres home,” members wrote in a letter responding to Historic Richmond’s proposals, adding that it opposes any attempts by the city or Richmond Public Schools to bypass processes meant for historical buildings as it considers the proposals.

Bob Balster was sharply critical of Richmond Public Schools for their lack of management of the building. The former president and current board member of the historic district said that the association has been keeping track of the building’s decline for decades and has alerted the division to its deterioration, calling the situation “demolition by neglect.” Since the division owns the property, he said, the onus is on them to do something about it.

“RPS has been a very poor landlord for that property,” he said. “It’s kind of surprising to me that the School Board doesn’t seem to have any memory of all the discussions that have been had around that building.”

Faruk agrees with Balster that the onus is on the School Board to do something about the building, and emphasized his belief that no one truly wants to demolish the building. But he said the Board is forced into making a decision it doesn’t want to make because of the division’s lack of funding, unless someone can step up and provide the money the building needs.

“If we had the money, I would not part with a single piece of property,” he told The Richmonder.“I wish we didn’t have to do that.”

Debate over the building’s value, condition

Balster said that while the building is in bad shape, the foundation or “bones” of the building are very solid. He invited the then-3rd District city and school elected officials to see the inside of the building in 2023. Current City Councilmember Kenya Gibson, who was the school board member then, vocalized support to preserve the building.

Gibson reiterated that support during a recent town hall, and in a statement to The Richmonder.

“Its a really beautiful building. I’ve been inside,” she told attendees. “And my hope is to ensure that the building is preserved in some fashion.”

The value of the building was listed at $9 million as of March 2025.

Crump and Balster said that they were under the impression that the building was going to be surplused to the city for it to sell the structure on the schools’ behalf.

At one point in 2009, School Board members did vote to surplus Thirteen Acres to the city, though the transfer never took place. That changed in March this year, when the Facilities & Vacant Properties Committee floated the idea of sunsetting the building before demolishing it due to concerns of it becoming a safety hazard. It is unclear why that change occurred.

“It is a beautiful house but in a significant state of disrepair,” Faruk said.

He emphasized that the building is unsafe, especially at a location that is so close to children. For years nothing has been done with the building, and residents and parents have seen that and expressed that to him.

“They’ve seen this building just sit there, so the message they’re getting is, ‘Okay, clearly it’s not going to be renovated and used. In that case, can we at least get rid of it,’ because it keeps falling into disrepair and it is a safety hazard in many cases,” he said.

Sera Davenport, a resident living in the district who also attended the town hall meeting, learned of the topic when she was at the meeting but echoed what Faruk has heard from residents.

“If we haven’t been able to find a use or good purpose for this building for such a long time, it could be of real benefit to the students that are here as a green space instead of having vacant property,” she said.

While the Board did not officially vote on the matter, it agreed to better explore the recommendations.

Faruk said he would love to see the building be used as a space for student wellness and mental health, or as a community space for residents. But that seems impossible with the funding constraints the division has. He noted that other schools in his district, like Frances W. McClenney Elementary and John Marshall High School, need significant work as well.

Who pays, and how would a move work?

The School Board has a lot to consider if it were to proceed with demolishing the building, starting with whether or not it can even do so.

The city’s Commission of Architectural Review requires applicants interested in demolishing a historic building within a city recognized historic district, as Thirteen Acres is, to “show that there are no feasible alternatives to demolition.”

“The demolition of historic buildings and elements in old and historic districts is strongly discouraged,” the commission’s code reads.

If the Board is able to make the case that Thirteen Acres is beyond repair, the Board would have to consider how demolition costs would fit into an already tight budget. The committee has yet to learn how much demolition would be.

In her statement, Gibson said the division has other pressing infrastructure needs that could use the funding.

“I question prioritizing funding available to demolishing a building when there are other options available, but that is currently up to the school board to decide,” she said.

Both Crump and Balster believe that all of the proposals presented in 2023 are still viable today, including moving the structure elsewhere. Balster argued that the home could even be bought for someone to live in for at least $1 million. However, Crump said that Historic Richmond has not looked into cost estimates for any of the proposals, saying that it would be difficult to do so without having a specific plan of what the involved parties want to do with Thirteen Acres.

Crump said she has reached out to Rizzi since learning of the Board’s recommendation and is hopeful to talk about the building. She added that she is open to exploring other ideas outside of what has been previously presented.

“When we've had an opportunity to really sit down and have meaningful discussions with property owners and the community around important historic and cultural resources, we have been able to present concepts and ideas that have resonated with property owners and the community,” she said. “It’s never too late to do that.”

She said the division has done a great job in handling other historical buildings, like the restoration of Fox Elementary after parts of it were destroyed in a fire, and the Moore Street School located at George W. Carver Elementary, which is in the process of being surplussed to the city.

Crump and Balster strongly believe that the building is interwoven into the fabric of the community, and community members want to keep it. Demolishing Thirteen Acres means it can’t ever be replaced.

“You can’t build historic buildings,” said Balster. “Every time the city loses a beautiful historic building like that, we’re just a weaker and a smaller community. It’s just one more piece of Richmond falling away.”

Contact Reporter Victoria A. Ifatusin at vifatusin@richmonder.org