Data: Charts showing insights on Richmond's finances

The Richmonder held its first live event on Thursday. Titled "The (Real) State of the City," the goal was to educate the audience on the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for Richmond as a new administration begins.

As part of the presentation, David Poole, The Richmonder's Development Director, presented a handful of slides based on his deep dive into the city's finances as we enter a new budgeting cycle.

Collective bargaining

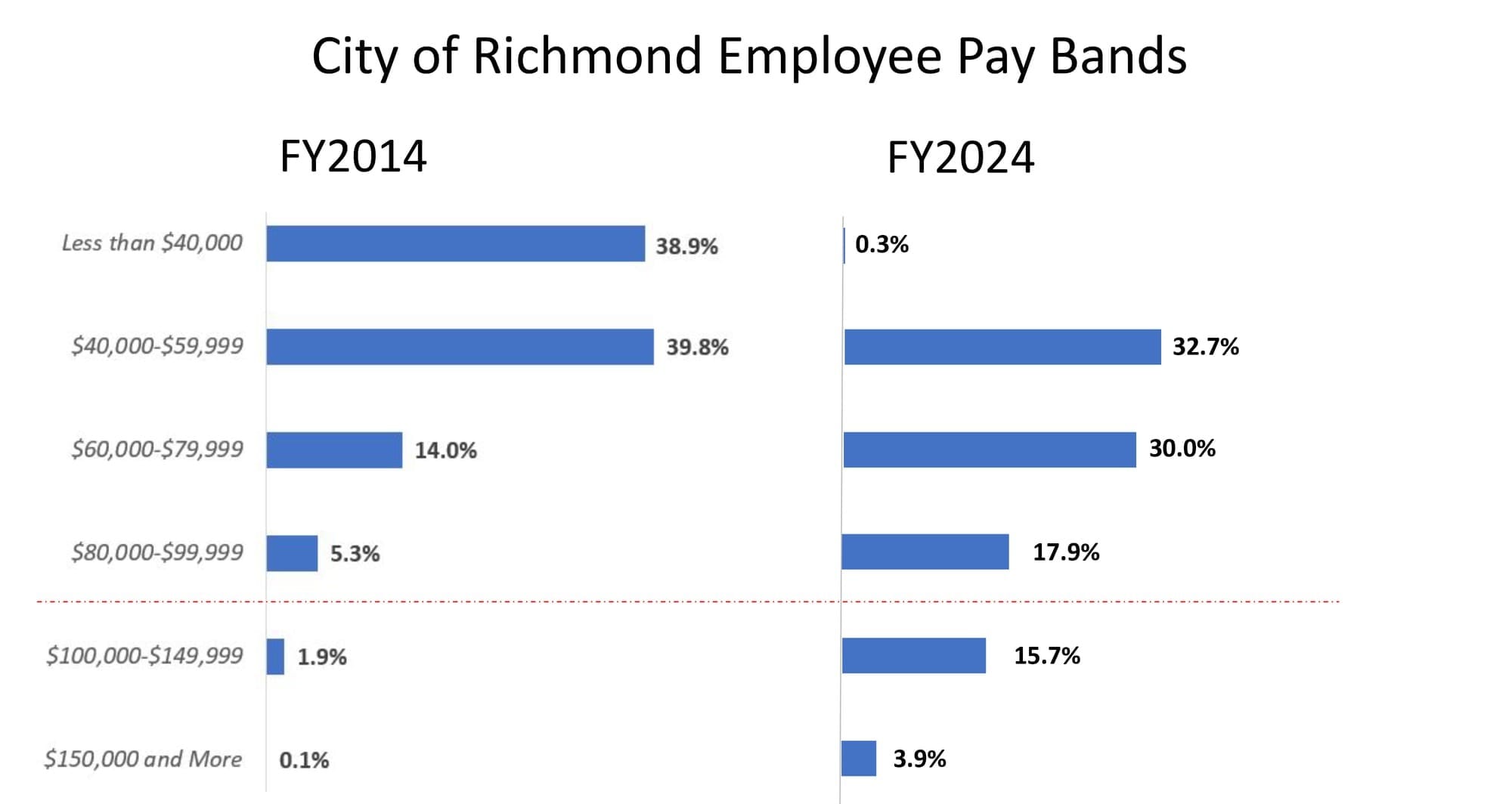

A decade ago, 40% of city employees made less than $40,000 a year. There has been a concerted effort to pay city employees a livable wage, particularly as it becomes more expensive to live in the city.

But there has also been significant movement on the upper rungs.

In 2013-14, only 2% of city employees made six figures. A decade later, that number had risen to nearly 20%. And that's before collective bargaining...

The General Assembly made the decision five years ago to allow public sector employees to collectively bargain for their salary benefits and working conditions.

Collective bargaining kicked in citywide on July 1, and will boost the salaries of some employees by 8% or more (entry level police officers, for instance, will receive an 8.6% increase starting in July).

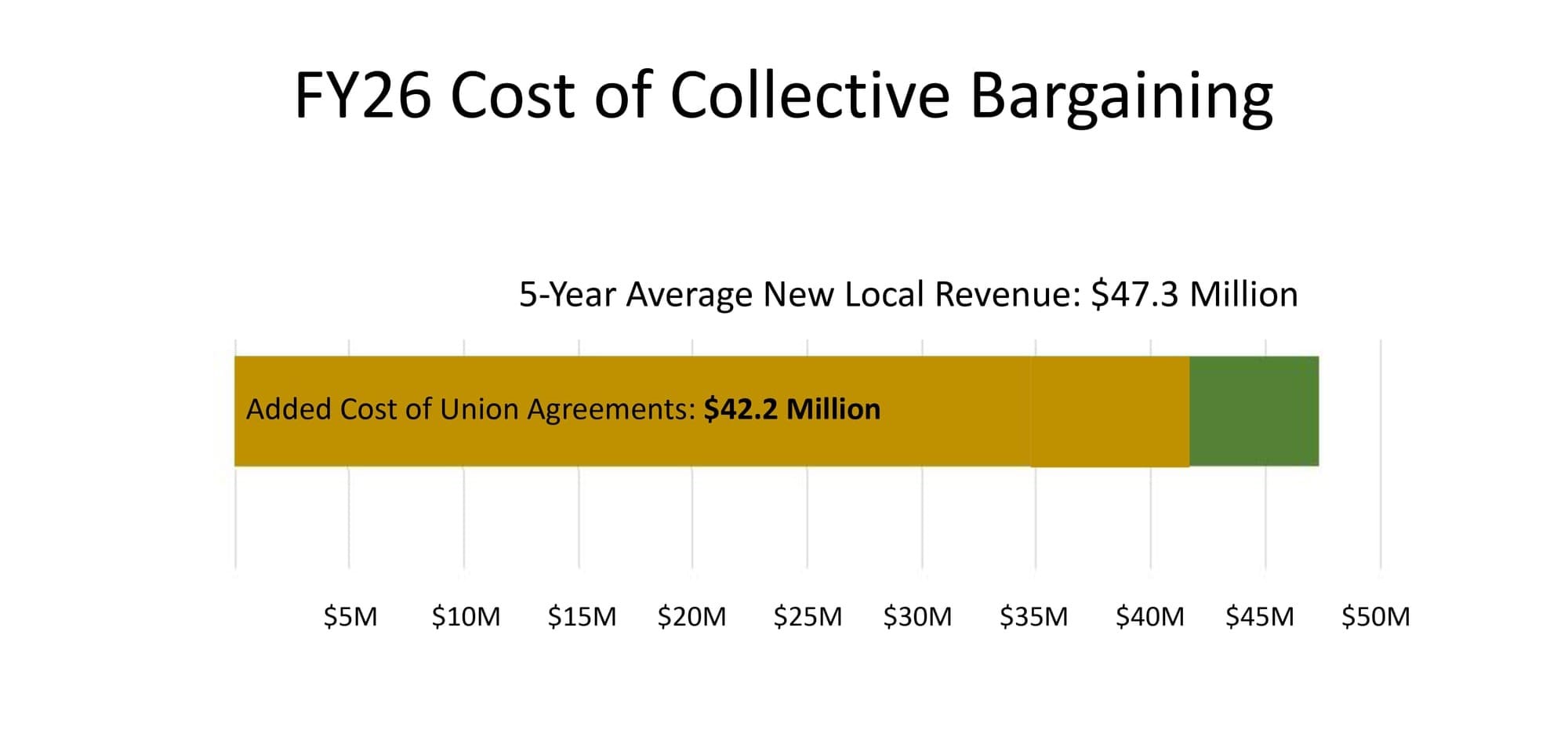

Current estimates suggest that in the upcoming budget year, which begins this July, collective bargaining will add about $26.2 million in extra salaries for city government workers, and $16 million for Richmond Public Schools employees.

To put that into perspective, consider that over the past five years, the city has brought in an average of $47.3 million in additional revenue each year, largely due to property tax increases (more on that in a minute).

When a potential rate cut was discussed last fall, most of the mayoral candidates agreed that the city couldn't afford to do it, in large part because of the additional financial obligations collective bargaining is about to bring.

Of the five bargaining units representing city workers, three have reached agreements with the city (the costs for the other two are estimated).

At Thursday's event, Mayor Danny Avula was careful to tout the benefits of collective bargaining as well as acknowledge the budgetary challenges.

"That's a significant increase in salaries, and that's not in itself a bad thing, right?" Avula said. "I think about the fact that 10 years ago, we had so many employees making under $40,000. That's a problem, right? We as a city really need to philosophically check ourselves and say, 'Is that OK?'

"So I don't want to blame this on unionization, because I think that has done some good things for the salaries of particular low-income wage earners, but it is a reality that we're going to have to work into the broader financial picture."

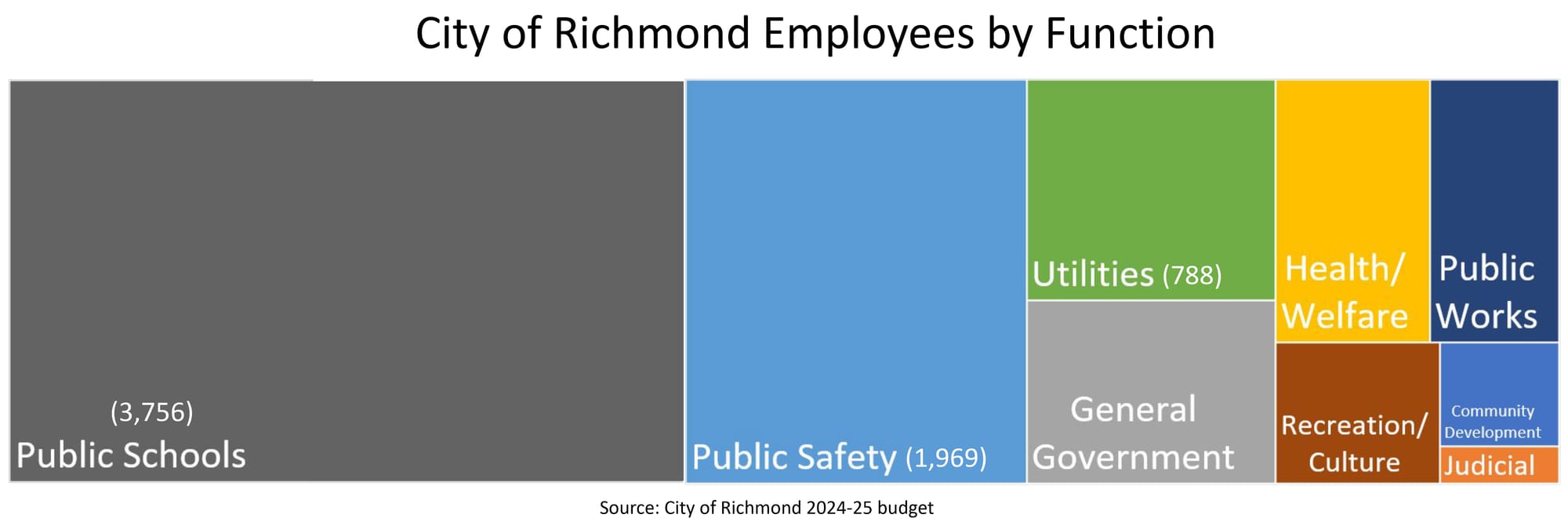

This visual shows the distribution of employees across the city's various departments. After education, public safety is the biggest employer, followed by utilities.

The Richmond Police Department, part of the "Public Safety" unit, has a large number of open positions. In July, the entry-level salary will grow to 103% of the average of surrounding localities — Poole noted that is one way where collective bargaining could enhance city functioning, by making wages more attractive against nearby localities.

Fiscal stress

When you look at Richmond, Poole said, it's an old city with a crumbling infrastructure that needs a lot of TLC, which we all saw with the water plant, and that puts an enormous stress on the city's finances.

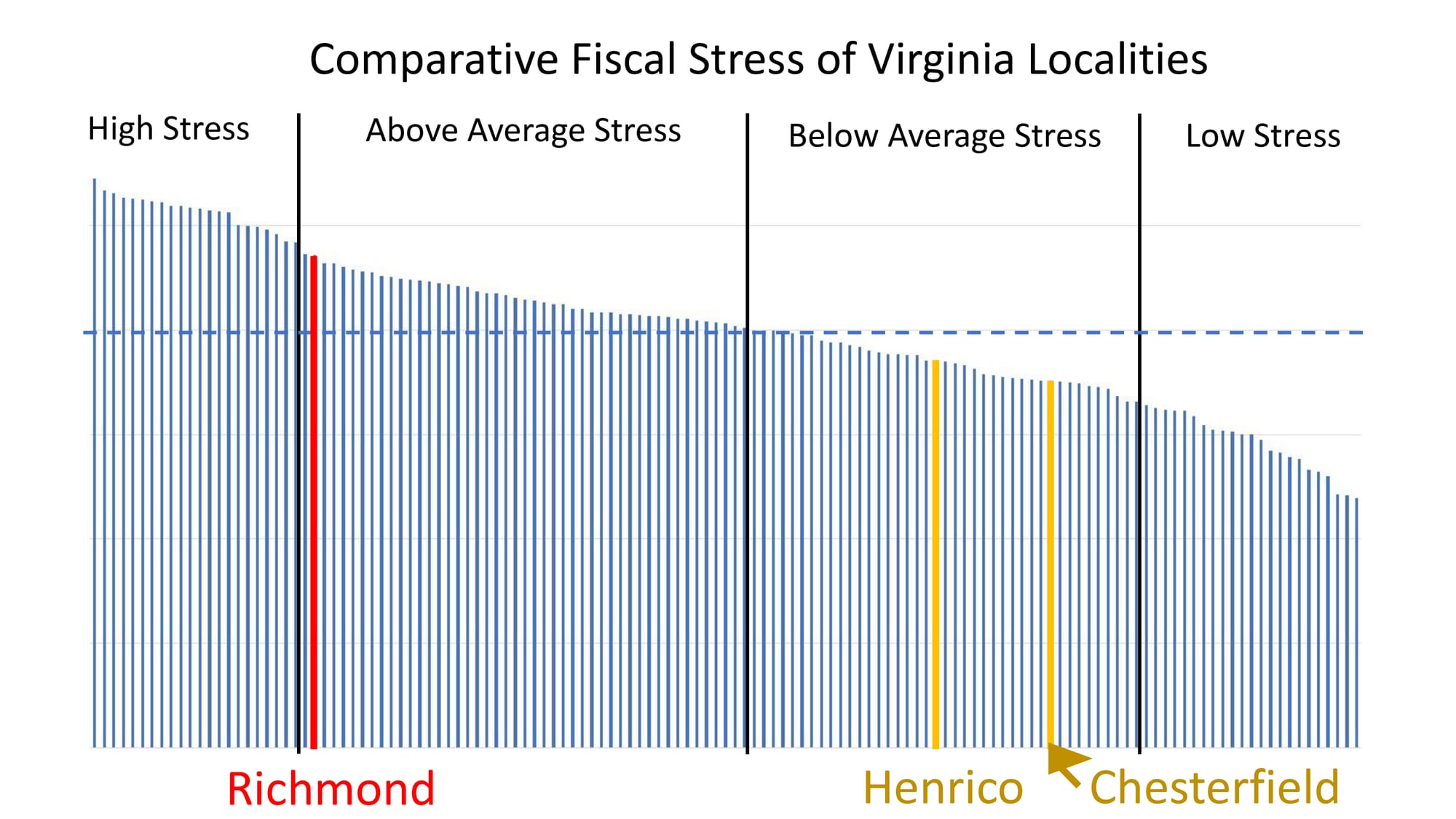

The state measures fiscal stress, and the most recent stress test showed that 20 of the 22 "high stress" localities are cities, and just two are counties. Richmond is just outside that band, and was rated "above average stress."

That's good compared to Virginia's other cities, but neighboring counties Henrico and Chesterfield shoulder a far lesser burden.

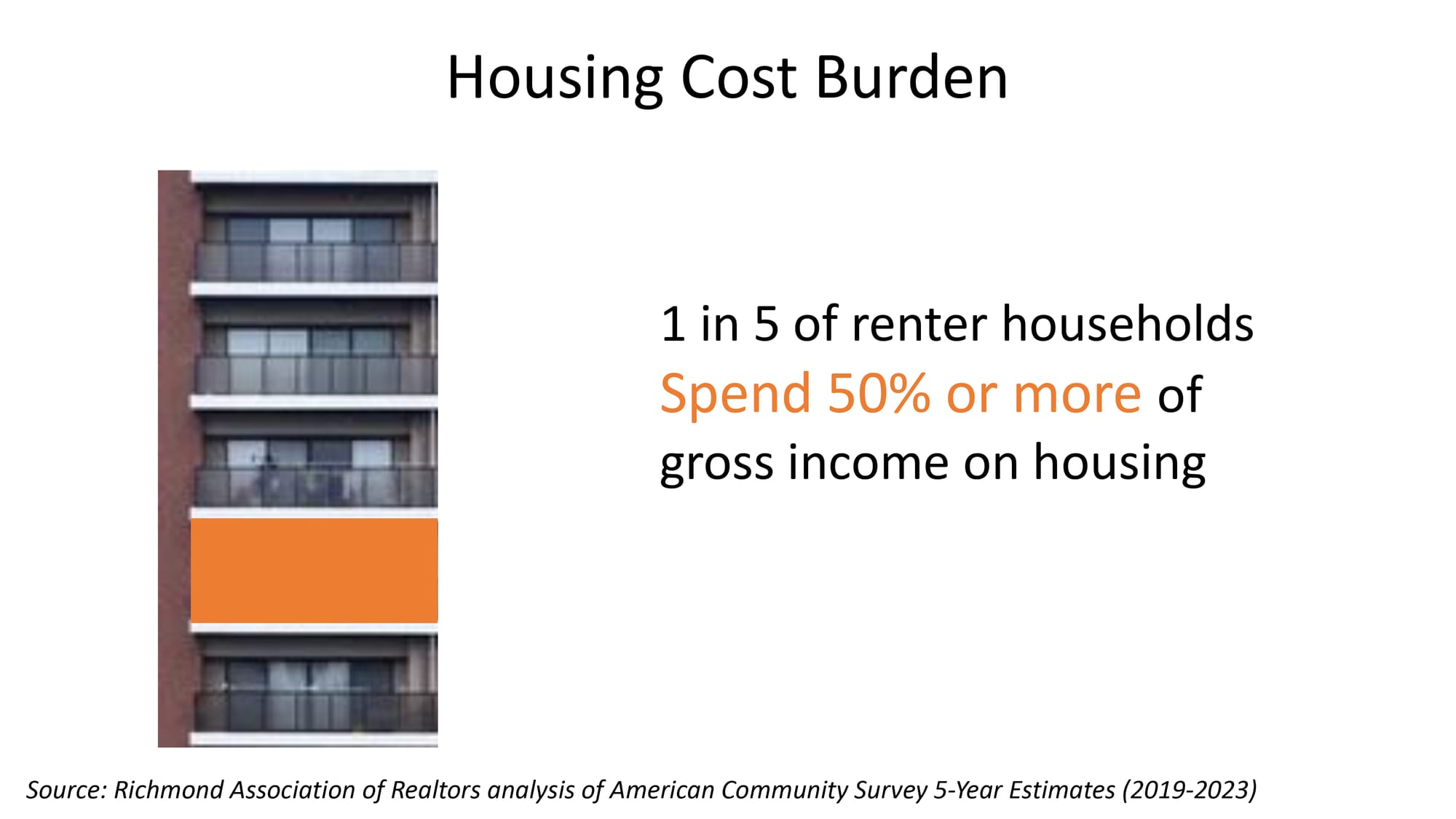

Richmond's fiscal challenges present themselves in many ways. The housing cost burden is a crushing blow to a lot of people, Poole said.

In the middle class, it's hard to get a foot on the first rung of the ladder by purchasing a home. Households that spend more than 30% of their gross income on housing are considered "burdened," and that is about half of the renter households in Richmond right now.

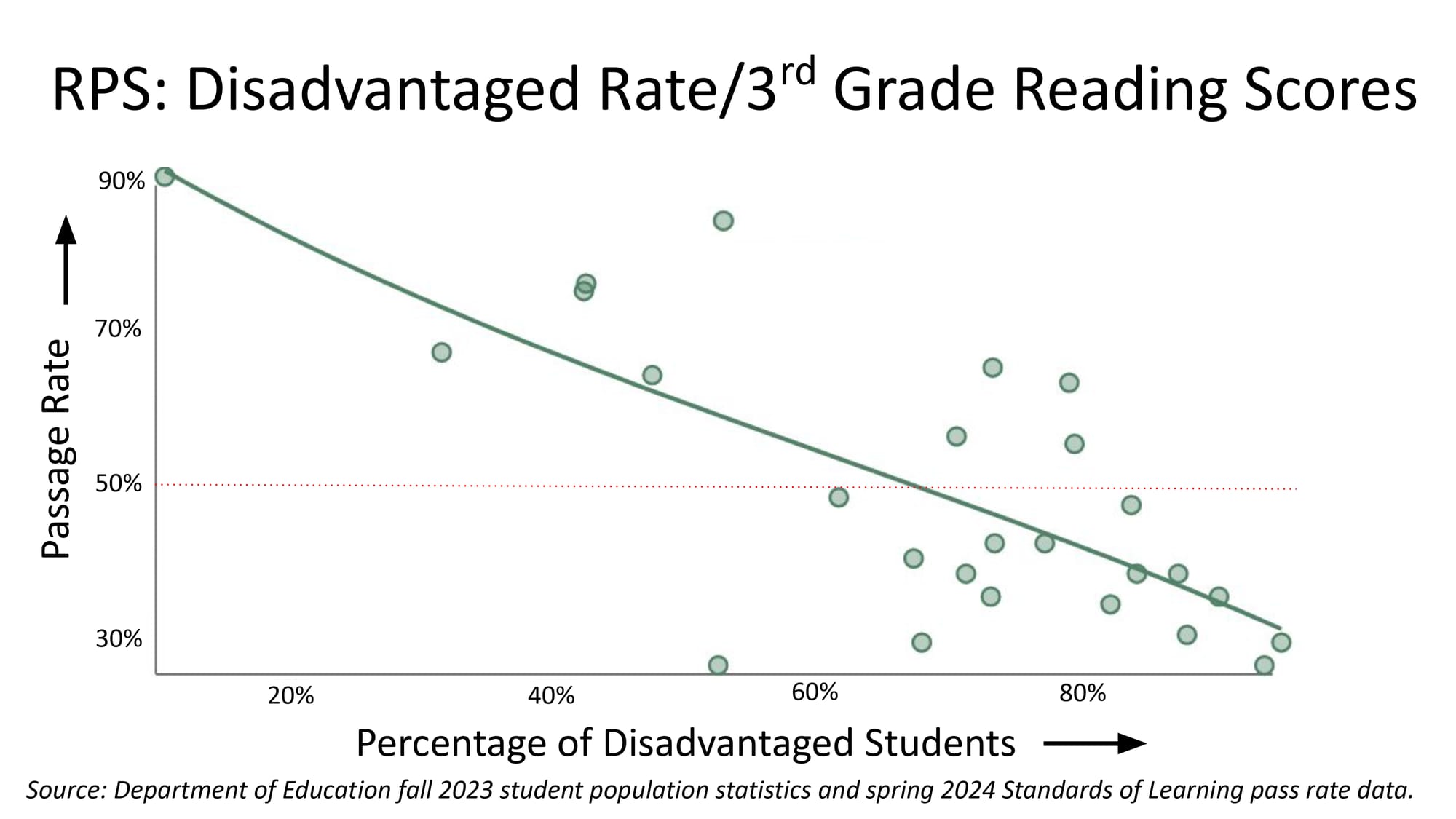

Poverty also has a big impact on schools. The more economically disadvantaged a school is, the less likely it is that children will pass the state's reading test in third grade, a key indicator of future success.

Disadvantaged children are those who come from homes that would qualify for free and reduced lunch, as well as Medicaid and other benefits.

Reliance on property taxes

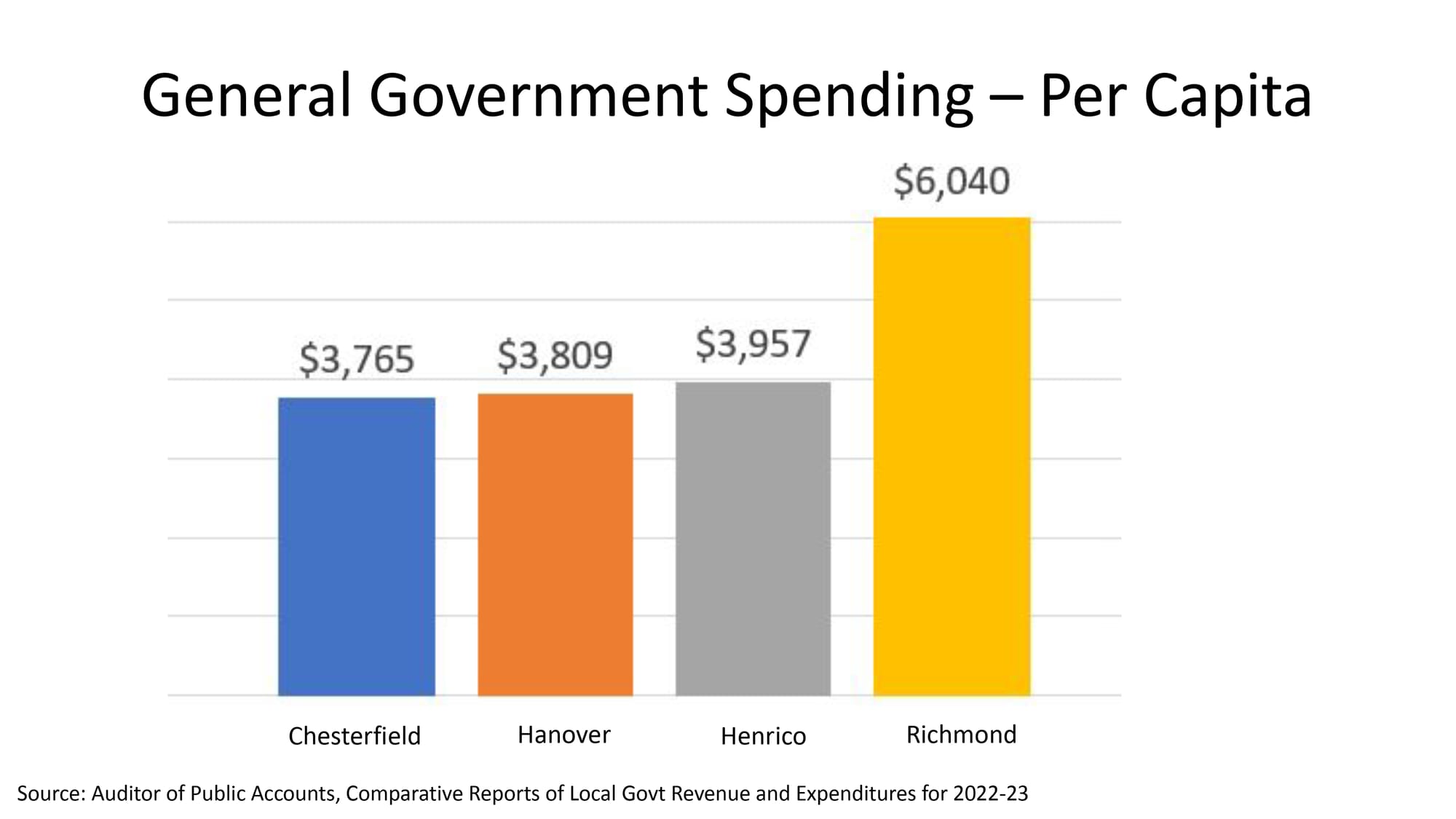

When you talk about the general cost of operating the government, and this is just the core government, not extras like gas or water systems, the spending per capita is much higher in the city than it is in the surrounding localities.

This money in the city is increasingly generated from property taxes. This is a combination of increased assessments — the median sale price of homes has gone up about 80% in the last four years — and the fact that the city has not changed the tax rate, which has resulted in a huge financial windfall.

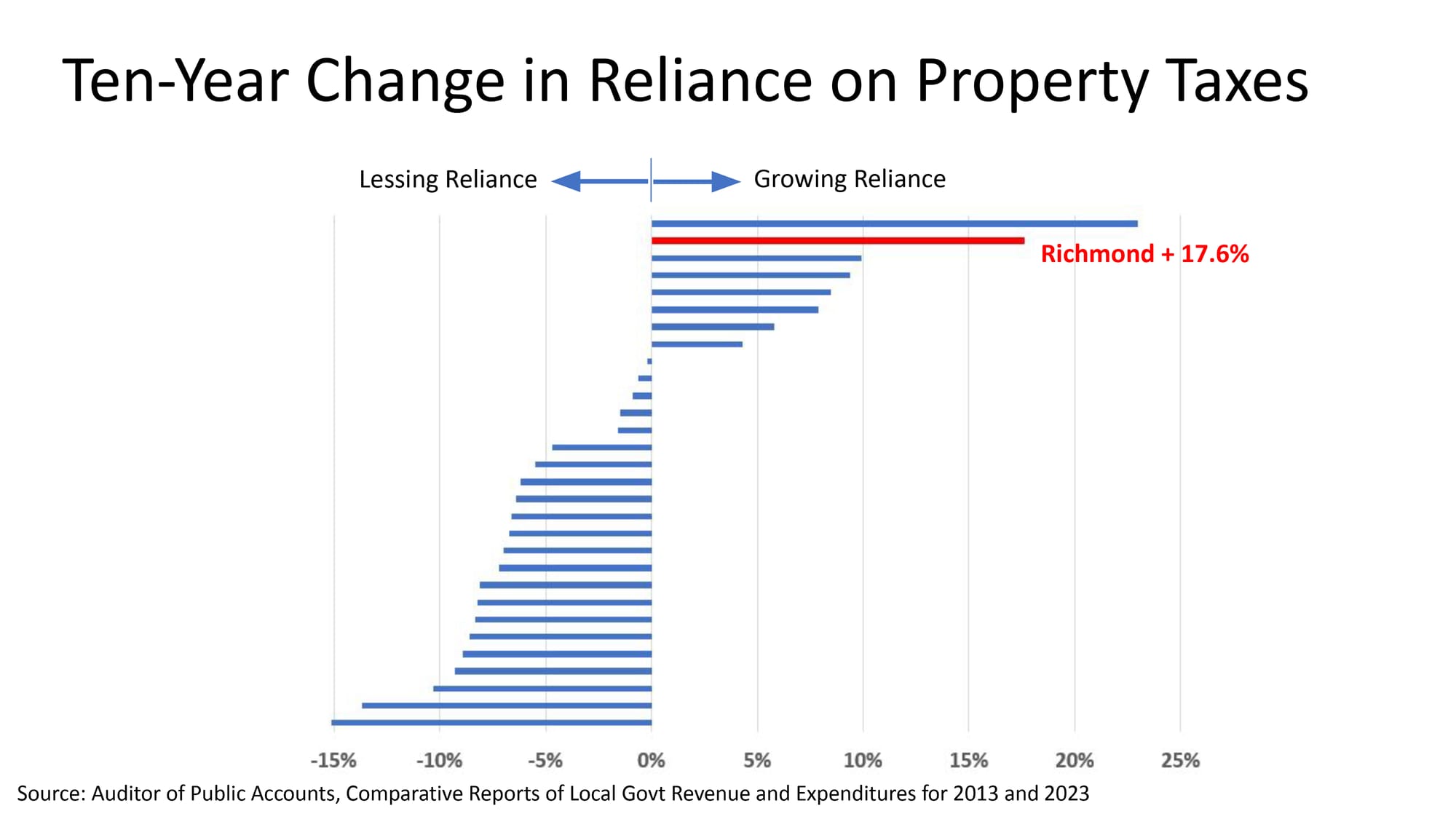

Comparing Richmond with other cities over the last 10 years, our reliance on property taxes is growing much faster than other cities.

Property taxes now represent half of all local revenue for the city, and City Council decided in November to provide a small measure of tax relief, but to leave the rate unchanged, citing the need to have flexibility in future budgets.

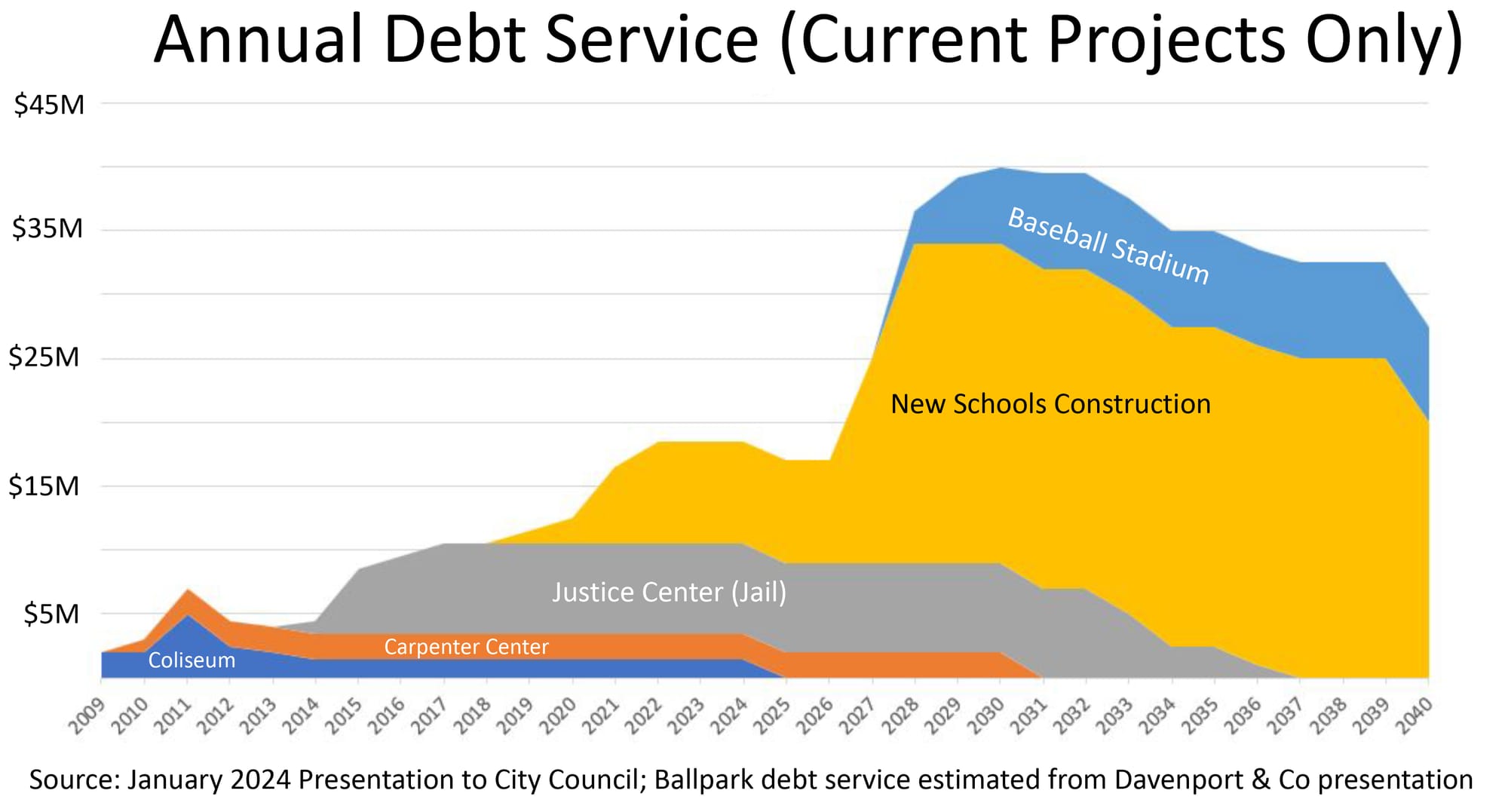

In addition to spending its tax revenue, the city has also dipped into its credit card.

Some of this infrastructure was badly needed. The old jail was a disgrace, Poole said, and has been replaced by a new facility. There hadn't been any new schools built in decades, and RPS is facing a huge backlog there.

There's also the baseball stadium, and while development at the site could result in that paying for itself, that development hasn't taken place yet, so the debt must be accounted for by taxpayers.

Debt service overall sharply rises over the next four years, limiting what the new administration will be able to accomplish while also protecting the city's credit rating and fiscal stability.

Pension bonds

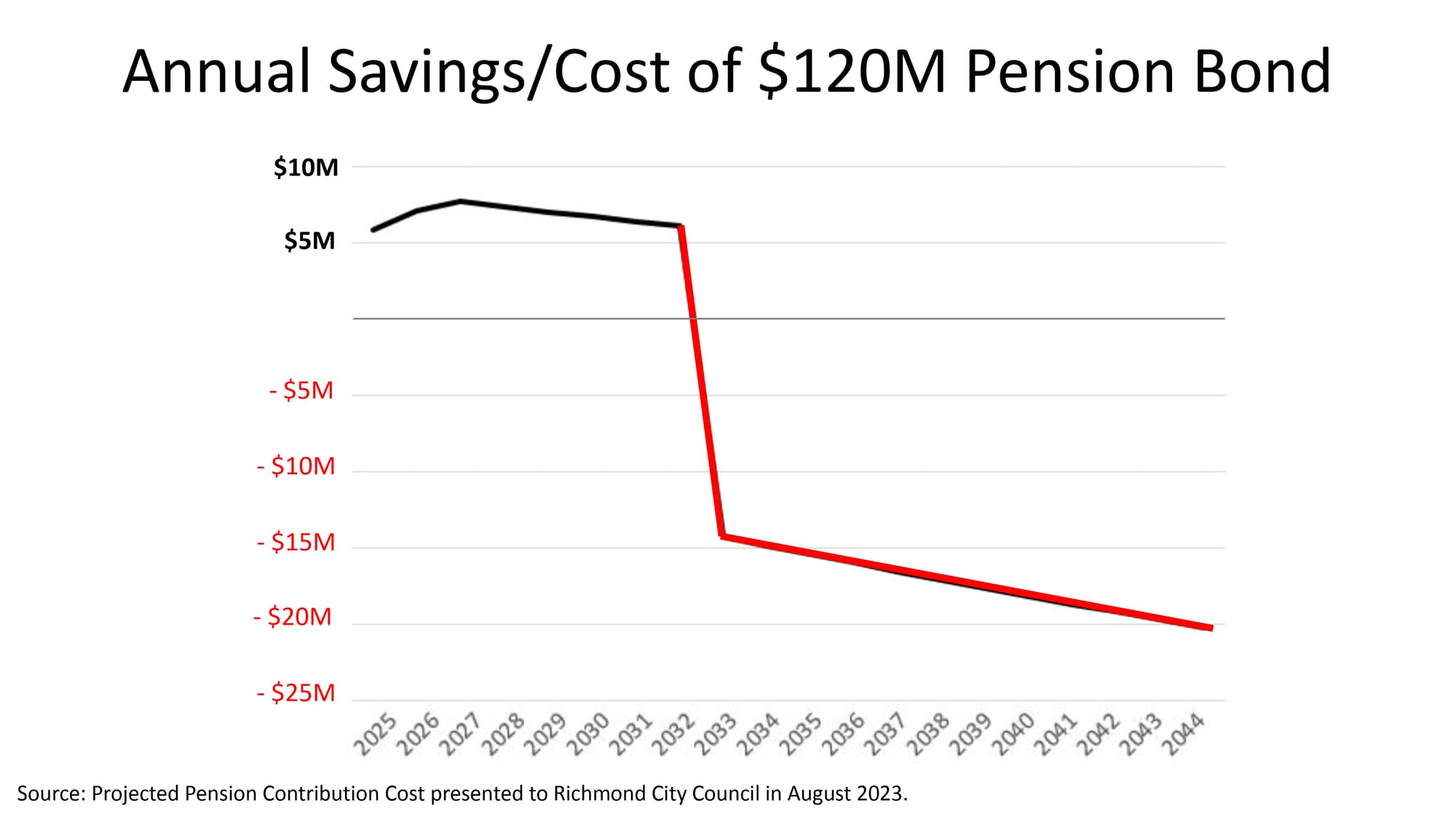

As part of Thursday's event, Eric Scorsone, Executive Director of the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at UVA, spoke on potential implications of the city's decision to take out $120 million in bonds to pay against future pension obligations.

For many years, Richmond ran its own retirement program for employees, instead of participating in the Virginia Retirement System (new city employees are now enrolled in the VRS). The city is responsible for funding those past pension obligations.

Last year, the city issued about $120 million in pension bonds. The bond funding brought the system up to 80% funded, which helped Richmond achieve its Triple-A bond rating, the highest available.

"It's essentially saying, we're going to take the proceeds (of the bonds) and invest them to make up the difference," Scorsone said.

He noted that they are best issued in times of down markets, by stable governments. He said that in Detroit, an unstable government issued the bonds, which contributed to the city's bankruptcy. He believes Richmond is on sounder footing, but noted that there are risks involved, and as the bills come due in future years, it will add to the city's liabilities if the money is not invested in a profitable way.

More from The (Real) State of the City: