Citywide cultural heritage plan stalls at Planning Commission over money, workability concerns

A wide-ranging plan for identifying and preserving historically and culturally significant buildings, neighborhoods and sites around Richmond ran into headwinds Tuesday night over concerns that its recommendations could strain city resources and have unintended consequences such as making housing development more difficult.

“I fear what costs I will be placing on the taxpayers of the city of Richmond,” said City Councilor Ellen Robertson (6th District), who also serves on the Planning Commission.

Several dozen people turned out to City Hall Tuesday to voice support for the 202-page Cultural Heritage Stewardship Plan, a proposal for how Richmond could preserve features and assets that have special meaning. But the Planning Commission never opened up a public hearing; instead, after a lengthy discussion, it voted to delay a decision until a three-person team could be put together to try to work out worries with city planning staff.

“We seem to be at loggerheads,” said Commission Chair Rodney Poole.

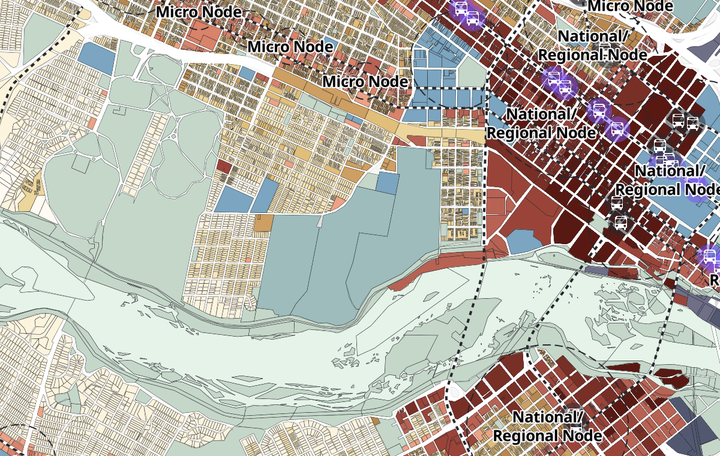

The stewardship plan has been in the works since 2024 and if approved would become part of the city’s master plan, Richmond 300. As part of the master plan, it would be used to inform future land use and development decisions made by city planners, the Planning Commission and City Council.

One of its key recommendations, that Richmond conduct a citywide architectural survey and archaeological assessment, provoked little disagreement.

“You can’t know what is precious until you know what you have,” said Paige Pollard of Commonwealth Preservation Group, a consultancy hired by the city to assist with the crafting of the plan.

While roughly 80% of Richmond’s buildings are considered “of historic age” — a classification for structures more than 50 years old — only those that are sited in the city’s 45 formally defined Old and Historic Districts are subject to rules about how they can be changed. Elsewhere, said Planning Director Kevin Vonck, “it’s just total laissez-faire.”

Community outreach undertaken as part of the stewardship plan found many residents weren’t interested in adding or expanding those districts. But emails to the Commission in support of the plan show a desire for some kind of additional protections, particularly in neighborhoods that have traditionally been overlooked because of large minority or low-income populations, as a wave of new development alters Richmond’s landscape.

“We need to strive to maintain what makes each of these neighborhoods unique rather than end up with cookie cutter neighborhoods,” wrote Forest Hill resident Laura Taylor. Church Hill resident Lauren Bowes urged the city “to protect and restore what exists NOW.” Realtor Jennie Dotts described Richmond as “besieged by developers.”

Whether the current version of the Cultural Heritage Stewardship Plan correctly balances that desire for preservation with the growth envisioned by Richmond 300 proved more debatable for commissioners, who balked at a number of the proposal’s recommendations.

Some of the critiques were on the smaller scale. One proposal that the city create “protections” for viewsheds like Libby Hill — the subject of bitter debates over the past decade and a half — caused particular consternation among some members, who worried they were promising to protect something that wasn’t clearly defined.

“If there’s nothing there documenting what that truly is or what it means, are we putting something in place that could impact future projects?” asked Commission Vice Chair Elizabeth Greenfield. “It makes me a little nervous when we’re going to protect something without any guidance on what we’re protecting.”

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.

Aspirations and expectations

Recommendations that the city reinstate a tax abatement program for owners who rehabilitate historic properties, overhaul its system of assessing property values and consider offering other financial incentives for conservation of existing structures also sparked some backlash.

“The whole abatement piece — we just did major restructuring of that because of the cost that is associated with that for the city. We cannot afford to do that,” said Robertson. Interim (but outgoing) Chief Administrative Officer Sabrina Joy-Hogg complained the plan waded too far into tax and financial policy that could have far-reaching consequences.

“I don’t think it is the role of this commission to get into tax policies or financial policies,” she said.

Not everyone had reservations. Commissioners Rebecca Rowe and Burt Pinnock pointed out the stewardship plan has been under development for more than a year.

“I’m not sure how we got to this point where it’s all of a sudden a surprise to everybody,” said Pinnock. “If we defer, I would ask that every commissioner, every council person and every department head bring to bear their specific concerns, chapter and verse. … There are hundreds of people, thousands of people supporting this.”

The two commissioners, along with Planning Department staff and Pollard, also argued that approving the plan does not commit the city to carrying out any of its recommendations but instead serves as a jumping-off point for further analysis of whether they are viable.

Like Richmond 300, the stewardship plan lays out a “laundry list” of possible options, said Vonck.

“It says, these are some things that are important to the community. There's a list of capital improvement projects in the master plan that are important to the community. We fund some of them, don't fund others,” he said. “And so to me, I don't see any financial obligations.”

Robertson seemed incredulous at that interpretation.

“When we talk about the abatement initiative, I don’t know how in the world anyone can say, let’s consider that and say zero dollars. It just doesn’t — that doesn’t register. I don’t get that,” she said. “If we adopt something with no sense of reality, of the potential of making it real, we are misleading everybody, in my opinion.”

The councilwoman repeatedly expressed concern throughout the evening that passing the stewardship plan in its current form would create expectations among residents that the city had committed to following the recommendations it contains.

“I know it’s a plan. I know not a thing in here has to be done, not one thing,” she said. “I don’t believe we do plans for that purpose. I believe we do plans for the purpose of seeing [them] implemented.”

Pinnock, however, in a separate exchange that drew sustained applause from audience members maintained that “creating no expectations for the public is worse” than setting aspirational goals that the city doesn’t meet.

“Having no vision is a nonstarter,” he said.

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org