City Council weighs whether more speed cameras are worth the cost

For months, members of Richmond’s City Council have been weighing whether they want to take advantage of a new state law that lets local governments place speed cameras at high-risk intersections or whether doing so would strain already tight city resources.

In December, City Councilor Stephanie Lynch (5th District) put forward a resolution calling for a study of the possibility and expressing support for the cameras’ installation. After five months of consideration and the completion of a five-page report, a Council committee recommended that the resolution be stricken.

“The goal of this paper has been met,” said Councilor Andrew Breton (1st District) this May. “We’ve gotten the study that we wanted.”

What comes next is up for debate. On June 2, Lynch urged Council to keep the idea alive as “a signal and an endorsement of a policy.”

“It is important for us as a Council to say we endorse this, we want to see the administration move forward in a thoughtful and planful way,” she said.

Members of Mayor Danny Avula’s administration, however, have repeatedly emphasized that any expansion of Richmond’s speed camera program will come at the cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars and hours of police time to review camera footage of speeding violations.

“Is automated enforcement effective? Yes, very much,” M.S. Khara, a deputy director of the Department of Public Works, told Council’s Land Use, Housing and Transportation Committee this April. “We don’t disagree with that.”

But, he also warned, “this will be a not sustainable kind of program for the city of Richmond until we fund it and budget it in advance.”

Monitoring school zones

Richmond already has a modest speed camera program that operates 26 cameras outside 13 schools during four hours of school days — two hours in the morning, when students are arriving, and two in the afternoon, when they depart.

Since the earliest of those cameras were deployed outside Linwood Holton Elementary on the Northside and Patrick Henry School of Arts and Sciences on the Southside in November 2023, they have racked up tens of thousands of citations for drivers speeding through school zones at more than 10 mph above the limit.

The devices have produced not only a damning record of the extent to which speeding is occurring in Richmond’s school zones, but also $1.9 million in fines. Those will eventually come back to the city: The 2020 state law that allowed local governments to begin using the cameras in certain zones directed any resulting penalties to the locality where the violations occurred.

When Richmond set up its program, the ordinance creating it specified penalties would go into a special fund called the Vision Zero Action Plan Fund, which would first pay for the cost of carrying out the program and then put any leftover dollars toward safety programs aimed at reducing traffic fatalities.

The fund, however, wasn’t created until this year’s budget cycle, and it won’t be formally established until July 1, when the budget goes into effect. So while Richmond drivers have racked up $1.9 million in fines, the city “can’t touch” it until then, RPD Maj. Ronnie Armstead told members of Council this May.

Ross Catrow, a spokesperson for the city, confirmed that the money is currently being held by the city’s speed camera vendor, which operates Richmond’s program under a $5 million, five-year contract. (The contract was initially signed with Conduent, but technology company Modaxo purchased divisions of Conduent that handled traffic enforcement in 2024.)

“City staff thought it best to wait for the state-level legislation to finalize before creating this special fund,” he said in a statement.

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.

High-risk intersections

Because Virginia is a Dillon Rule state, local governments cannot do anything that the legislature doesn’t specifically give them the power to do. That meant until the 2020 law, governments like City Council had no power to use speed cameras to enforce speed limits.

That year, the General Assembly allowed the cameras in school and work zones. And in 2024, it expanded the law to include “high-risk intersection segments,” defined as a section of road that is not more than 1,000 feet from a school property and is adjacent to an intersection where a traffic fatality has occurred since Jan. 1, 2014.

(While the legislature passed further changes to the law earlier this year, they were vetoed by Gov. Glenn Youngkin, who cited privacy concerns and outstanding questions about their “precise benefits.”)

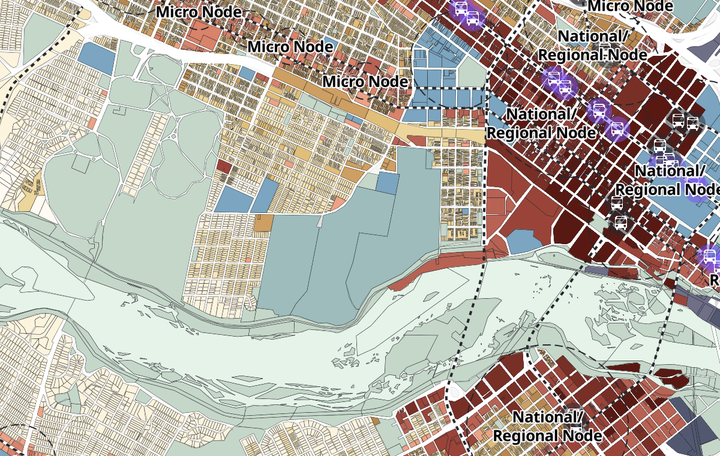

Richmond’s Department of Public Works has identified 31 locations that can be considered high-risk intersections.

But unlike school zone cameras, which can be funded from the proceeds of the tickets they generate, all of the money that comes from violations recorded in high-risk intersection segments is sent to the state — a provision of the law that many local governments like Richmond are eager to see changed.

“You may not see this money back again,” Khara warned City Council.

DPW has estimated that running two cameras at each of six schools where high-risk intersections are located would cost $864,000 annually, with operation and maintenance of the equipment requiring about $576,000 and an additional $288,000 needed to pay four off-duty police officers to validate the citations.

Armstead said that job has to be done by sworn officers, “because you have to check people’s driver’s license, you have to run their tags, make sure whose car it’s coming back to.”

Under the city’s current $5 million contract with Conduent, each camera costs $3,629 per month to operate, with the number of the devices capped at 26. RPD also employs four part-time officers and one full-time officer to validate the citations, at a cost of roughly $400,000 annually.

The price tag of potentially expanding that program isn’t the only concern. Councilor Nicole Jones also worried that putting more speed cameras on the city’s roads could further inequities by targeting certain demographics and not others.

“We all are in favor of adding tools to our toolbox,” she said, pointing to recent pedestrian deaths on Hull Street and elsewhere. (The city’s Vision Zero dashboard maps the location of all traffic injuries and fatalities dating back to 2016.) But, she told The Richmonder, “we haven’t even done our due diligence to see what the cameras that are already out there are doing.”

“Before we move to say let’s get more cameras, we need to be looking at whether these cameras are even working,” she said.

Still, Lynch said, many community members “are begging us to do more on traffic safety.” They include Open High School Principal Clary Carleton, who wrote a letter to Council this June supporting the addition of a camera on a stretch of South Belvidere Street that is crossed by many students catching the city bus.

“I grow ever more anxious about them crossing S. Belvidere having witnessed cars recklessly driving well over the speed limit with no consequences,” Clary wrote.

Momin Khan, an Oregon Hill resident who came to City Council June 2 to speak in support of the resolution, said that if Council doesn’t pass Lynch’s proposal, “it’s very unclear what the city’s intention is, if they’re taking this seriously.”

Significant investments over the past few years in traffic-calming infrastructure is “really helping,” he continued. “We would like to see that momentum kept up with a commitment to install these speed cameras.”

The high-risk intersection proposal is expected to be discussed again at City Council’s June 23 meeting.

This story has been updated to note that Modaxo purchased divisions of Conduent in 2024.

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org