Avula says he cannot back Gilpin redevelopment plan unless housing authority meets eight demands

Mayor Danny Avula has said he cannot back the Richmond housing authority’s plans to redevelop Gilpin Court unless the authority takes several major steps, including withdrawing its proposal to transfer any part of the court to a subsidiary.

“For too many Richmonders, and especially Gilpin residents, there is not clarity about the goals of redevelopment, nor is there understanding about the specific action steps required to achieve success,” the mayor said in a lengthy release Thursday afternoon. “Our city’s families deserve better.”

To gain his support, Avula said the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority would have to meet eight requirements, most of them focused on increasing resident and community engagement and ensuring tenants have the protections they need to avoid displacement.

Because the housing authority is legally distinct from the city, the mayor has only limited direct power over RRHA’s plans. Under federal regulations, the authority will need a letter of support from him to get approval for its proposal, as well as other proof it has consulted with the local government.

“Sign off at the highest level in the city is needed,” said a city spokesperson.

But Avula’s bully pulpit may be his most powerful tool, and the timing of his statement comes less than a week ahead of RRHA’s first board of commissioners meeting since July, when that body is expected to consider the Gilpin plans again. It also comes as residents voice distrust with the authority’s plans and City Council prepares to consider a resolution halting further work with RRHA’s chosen developer until council authorizes it to go forward.

Councilor Stephanie Lynch (5th District), who along with Councilor Kenya Gibson (3rd District) has been one of the most vocal critics of the authority’s approach, said Thursday that she hoped Avula’s statement “sends a message to the board” of commissioners.

“I was very encouraged to hear him line up with what City Council and other advocates have been asking for,” she said. “The things he is asking for RRHA to do are in no way outlandish or outside of scope. It is actually what they are required to do.”

Gibson, who represents the district where Gilpin sits, said she had been asked by residents about Avula’s position on the project.

“So I appreciate that he’s made a public statement that underscores the need for tenant engagement and a City Council vote,” she said. “There are obviously a lot of details that need to be discussed, but I’m thankful that he shares similar concerns with RRHA’s approach thus far.”

Of the eight asks Avula lays out in his statement, the most significant is that RRHA scrap its plan to convey Gilpin to the Richmond Development Corporation, a nonprofit subsidiary of the authority that has existed for years but rarely been leveraged, until concerns about it can be addressed.

Steven Nesmith, the authority’s CEO, has sought to make the subsidiary an active arm of the authority that can further redevelopment and fundraising efforts without facing some of the constraints that surround RRHA. Subsidiaries are common among public housing authorities, Nesmith has pointed out — Charlottesville and Alexandria are among the Virginia cities that have set up such entities.

But confusion has surrounded the RDC proposal. Residents and some city officials have asked why it is necessary to the Gilpin redevelopment plans when the ongoing Creighton redevelopment didn’t require it. Others have been wary of the composition of the subsidiary’s board, which is stacked with high-level RRHA officials, and what the transfers could mean for the protection of some of the city’s most vulnerable residents.

In his Thursday release, Avula singled out “major concerns about RDC’s governance structure.”

“It is concerning that the majority of RDC board seats are held by RRHA staff members,” he wrote. “The majority of the board should be long-term community stakeholders, and the city of Richmond should have permanent representation on the board.”

Angela Fountain, a spokesperson for RRHA, said the authority had no statement on Avula’s release Thursday but intends to hold a press conference Friday.

Avula calls for better engagement, information on plans

Gilpin Court, a community cut off from the rest of Jackson Ward by Interstates 95 and 64, is Richmond’s oldest and largest public housing development, built in the early 1940s and home to roughly 2,000 residents.

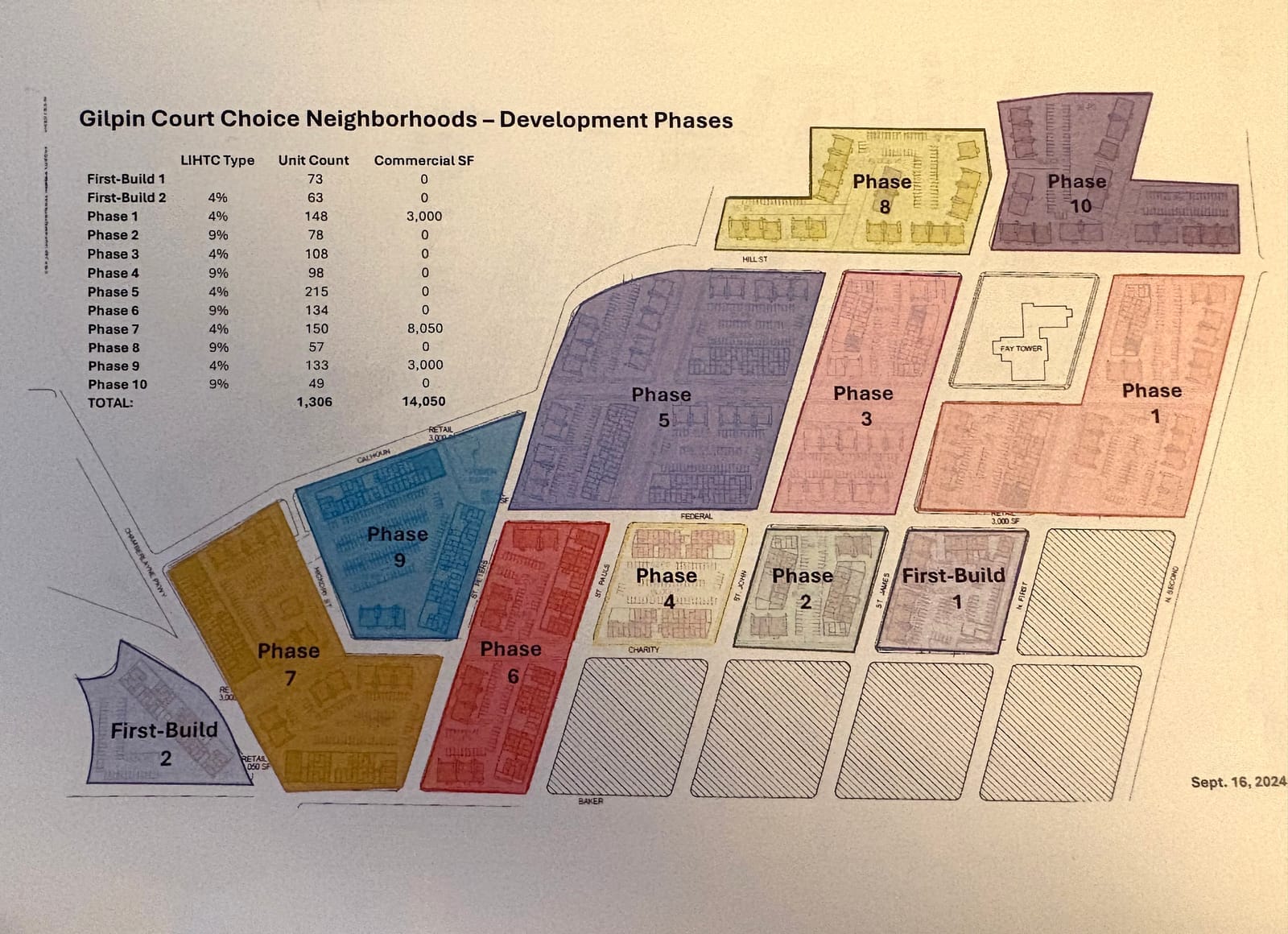

Efforts to redevelop its increasingly crumbling structures have been put forward multiple times over the years, with the most recent push beginning in 2021. In November of that year, RRHA got a $450,000 federal grant to craft a plan for how to rebuild and revitalize the court as a mixed-income community.

The result was the Jackson Ward Community Plan, a 121-page document based on extensive public engagement that sketched out the transformation of Gilpin into a mixed-income community. Among the details it included were a proposed 11-phase construction plan and the broad strokes of how relocation would be carried out.

Avula on Thursday endorsed that plan as the guiding document for the Gilpin redevelopment, saying that RRHA will need to seek approval of it from City Council, a move that would incorporate the document into Richmond’s master plan. Nesmith has previously said he doesn’t believe RRHA is legally required to get Council approval of its redevelopment plans.

“Deviations from the plans require clear justification, and the opportunity for the public to discuss in a public process prior to its transmission to Council,” he said.

In particular, he asked the housing authority to confirm it intends to follow the approach laid out in the plan for replacing the existing 781 units. That document called for the construction of 450 replacement units on the current Gilpin Court site, with the remaining 331 units being developed off of the site.

All of those units would be occupied by residents using project-based vouchers, a form of voucher that is tied to a specific location.

While vouchers have increasingly become a significant part of public housing redevelopment nationally, they come with different protections than traditional public housing and often leave residents concerned that they will end up with no place to call home.

Any redevelopment plan should include “zero tolerance for displacement of any kind,” said Lynch.

Several of Avula’s requests focus on those concerns, calling for the development of a tenants bill of rights that would ensure all residents have the right to return to Gilpin after redevelopment and a commitment to working with residents to make sure they meet all of the federal criteria to receive a voucher.

“RRHA must make every effort to assure all Gilpin residents receive robust support, regardless of current lease compliance status,” he said.

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.