After Church Hill teardowns, Richmond eyes steep penalties for unapproved demolitions

It could become far more expensive to tear down a building without permission in some of Richmond’s most historic neighborhoods.

Under a proposal moving through City Council, anyone who razes, demolishes or moves a structure that is located in one of the designated areas without prior approval could be required to pay a penalty of up to twice the assessed value of the building.

Richmond has seen “enough sporadic threats to historic buildings that people felt like they wanted a tool” to proactively avoid unnecessary demolitions, said Councilor Katherine Jordan (2nd District), who is the chief patron of a resolution that would start the process of crafting the new rules.

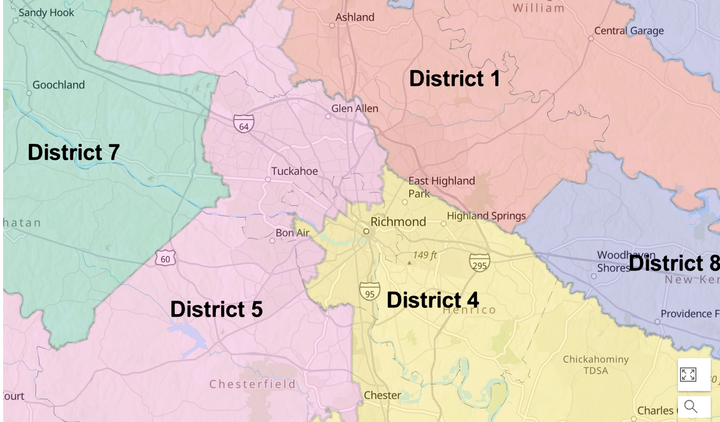

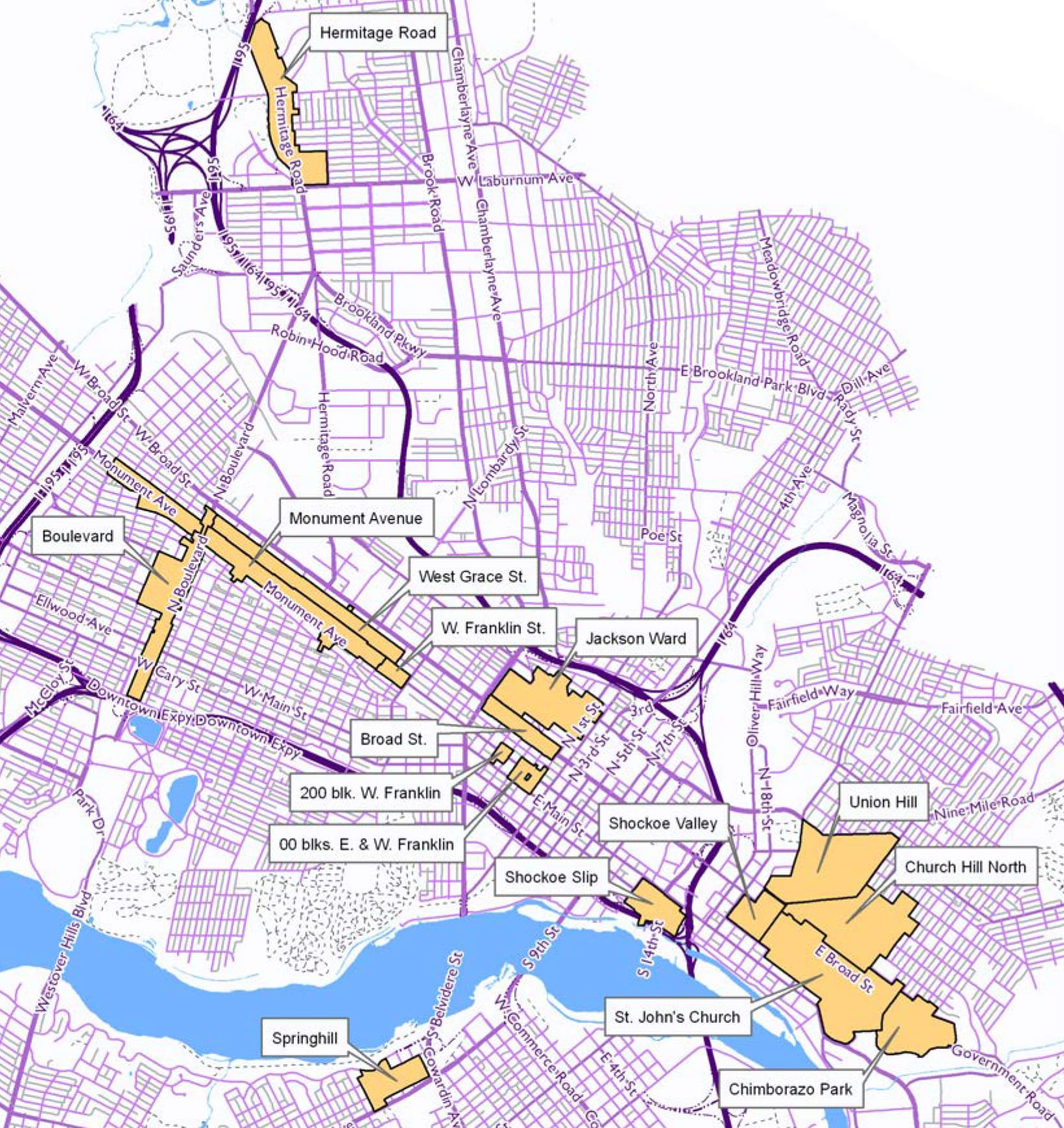

The penalties would only apply to teardowns of buildings in Richmond’s “Old and Historic Districts,” a designation that covers 16 areas and 29 individual properties. In total, about 4,000 of the city’s roughly 68,000 buildings would be subject to the potential fines.

Penalties would also not be imposed on demolitions that had been approved by the city through its Planning Department and the Commission of Architectural Review, a body that has oversight of any changes that are made to the exterior of structures in Richmond’s Old and Historic Districts.

Anyone trying to demolish a building in an Old and Historic District has to get a “certificate of appropriateness” from CAR. Under city code, CAR can’t issue that approval “unless the applicant can show that there are no feasible alternatives to demolition.” Demolition of buildings that are “beyond the point of being feasibly rehabilitated” or are “not a part of the historic character” of the district is allowed.

“People can take things down,” said Sharon Ebert, Richmond’s deputy chief administrative officer for economic and community development. “Just don’t do it outside the process.”

The proposal has already gained the support of Mayor Danny Avula’s administration, although it is still in its early stages.

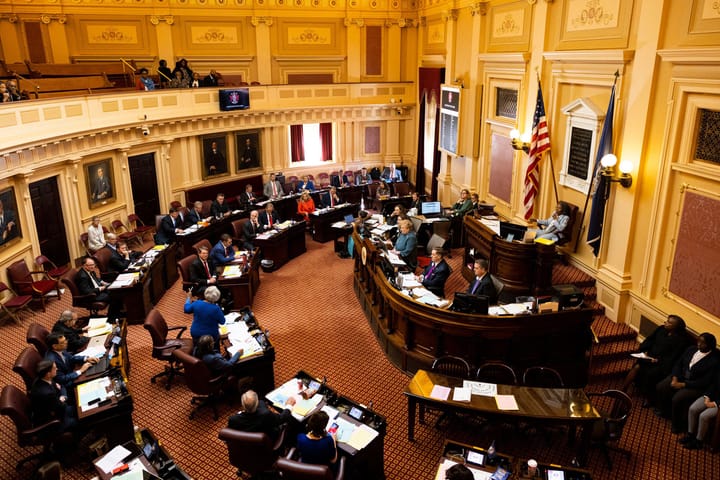

Jordan’s resolution, which a Council committee voted Tuesday to pause for 30 days in order to make sure it’s aligned with the latest version of Richmond’s proposed Cultural Heritage Stewardship Plan, simply declares that the higher penalties are necessary. If it gets full City Council backing, an ordinance would then be prepared laying out the enforcement process and the exact fines. That ordinance would also require Council approval.

“The hard part will be determining what the fee structure is,” said Ebert.

Church Hill demolitions

Backers of the new penalties have pointed to the 2023 teardown of two old storefronts near Chimborazo Park in Church Hill as evidence that the city needs a more powerful stick to deter property owners from demolishing buildings that could have special historic and cultural value.

In that instance, a developer pulled down two commercial structures at 3304 and 3306 E. Marshall St. that were over 100 years old, despite being told by Richmond’s Commission of Architectural Review that it would have to preserve their facades.

Richmond ultimately was only able to fine the developer $200.

That’s just not enough to deter anyone,” Jordan told the City Council’s Land Use, Housing and Transportation Committee Tuesday.

Councilor Andrew Breton (1st District) noted that the consequences are stark: “Once these historic buildings are demolished, there’s no getting them back.”

The incident led Richmond to push for state legislation that would give it the power to increase those penalties. Virginia law at the time allowed counties to levy hefty fines for unauthorized demolition in a historic district but didn’t extend the right to cities.

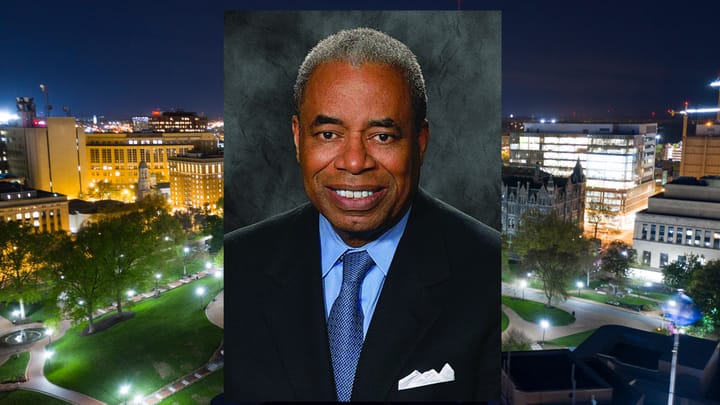

In 2024, a bill carried by Del. Delores McQuinn (D-Richmond) changed that, opening the door for Richmond to set a penalty of up to twice the market value of a property in the narrow set of circumstances that the law describes.

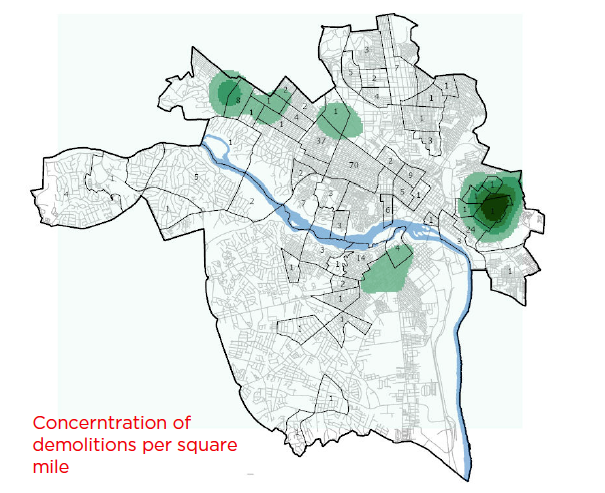

Jordan acknowledged that the kind of teardowns her proposal addresses aren’t “rampant” in the city. But “it has happened,” she said, and it’s a concern many residents have voiced as Richmond continues its sweeping overhaul of its 1970s-era zoning. City maps show the greatest concentration of demolitions in recent years in the East End.

“We have been hearing from constituents constantly during the zoning refresh process that one of the end results might be incentivizing developers to knock down old properties and build something more dense,” said Jordan. “Now that we have the ability to pass such an ordinance, it’s important to follow through on that.”

Almost a quarter of Richmond’s buildings are over a century old, while 81% are at least 50 years old. Approximately 22,000, or one-third, are listed on either the state or national historic registers, a designation that signals a site has value but that offers no concrete protections.

Historic preservation, and the threats posed to it by demolition, have been repeatedly noted in city planning documents. Reducing the demolition of historic buildings is one of the objectives of the Richmond 300 master plan, while the Cultural Heritage Stewardship Plan calls for passage of an ordinance like the one Jordan has proposed to increase demolition penalties.

While the Stewardship Plan stalled at the Planning Commission this May over concerns it could have unintended consequences for housing development and city revenues, the penalty recommendation remains in a revised draft set to go back before the commission this November.

In an August memo about the Stewardship Plan, Richmond Director of Housing and Community Development Merrick Malone and city staffer Rachel Hightman raised some concerns that increasing demolition penalties in historic districts could “negatively impact low to moderate-income residents” and keep property owners from determining “the best future use of their property when the structure has come to the end of its life.”

Malone and Hightman recommended instead that the city consider more narrowly tailoring the ordinance to only apply to structures listed on historic registers or identified as contributing to registered landmarks.

However, Avula administration officials said this week that the department’s concerns have been addressed. Malone told The Richmonder that his primary intention was to avoid “any barriers to affordability.”

Contact Reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org. This story has been updated to reflect that the Church Hill buildings in question were only required to preserve their facades, not the entire building.